A large luxury cruise liner is following the Northwest Passage from Alaska to Greenland, allowing over 1,000 passengers to visit some Inuit communities and to view glaciers, icebergs, and wildlife along the way. The ship left Seward, Alaska, on August 16 and is due to end the voyage in New York City on September 17. Both the Guardian and the Globe and Mail covered the highly controversial development.

The ship, the Crystal Serenity, has a crew of nearly 700 and holds 1,070 passengers on the sold-out voyage. The passengers have paid, per person, between US$22,000 and $120,000 for the lavish, 32 day trip. Other much smaller cruise ships have entered the same waters in recent years, but this vessel, over 900 feet long and weighing 69,000 tons, is certainly the largest so far. It suggests the likelihood of regular visits by mega-liners into this part of the Arctic.

It also suggests very significant implications for the land, the ice-free waters, the wildlife that depends on the pristine Arctic ecosystem, and the Inuit living in the small communities who will have to host the hordes of visitors. Whether the Inuit will suffer from the wealthy tourists or benefit from them is an important aspect of the controversy.

The first Inuit community the Crystal Serenity visited was Ulukhaktok, located on the west coast of Victoria Island in the Northwest Territories of Canada. A small hamlet of 400 people, visitors from the ship well outnumbered the inhabitants. Inuit leaders expressed fears that visits such as this by giant cruise liners could overwhelm the tiny, fragile villages. The two newspaper articles indicated that the industry is watching the development closely—a new, untapped frontier for cruising may be opening.

Professor Michael Byers, from the University of British Columbia and an expert on international law, referred to the cruise as “extinction tourism,” referring to possible harm to both the natural environment and the human communities. “Making this trip has only become possible because carbon emissions have so warmed the atmosphere that Arctic sea ice in summer is disappearing,” he said. “The terrible irony is that this ship—which even has a helicopter for sightseeing and a huge staff-to-passenger ratio—has an enormous carbon footprint that is only going to make things even worse in the Arctic.”

Prof. Byers did acknowledge that Crystal Cruises, the owner of the ship, has done an excellent job of preparing for the trip. It has spent three years planning for the voyage, anticipating many possible difficult scenarios and preparing well for them. The British Royal Research Ship Ernest Shackleton, an icebreaker, is accompanying the Crystal Serenity on the voyage. But the prospect of mass tourism in the High Arctic may well spell disaster at some point in the future, particularly if a tour company mismanages a cruise and a big ship crashes on uncharted rocks, of which there are many.

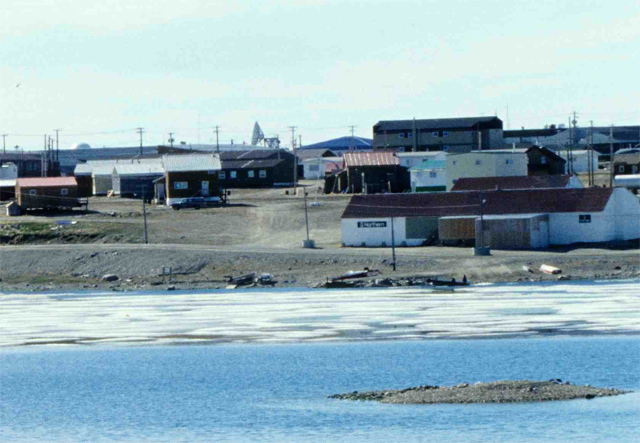

After it left Ulukhaktok, the Crystal Serenity moved on to Cambridge Bay, on the south shore of Victoria Island in Nunavut. With four times as many people as Ulukhaktok—over 1,600 residents—Cambridge Bay is better prepared for masses of tourists than the smaller village. Vicki Aitaok, the cruise-ship coordinator for Cambridge Bay, organizes visits from the various small vessels that pull into her town in late August and early September each year. The visits have normally been for just an afternoon, when the town welcomes about 100 passengers from the smaller boats. The visit by the Serenity required much more organization.

The ship was to have arrived in Cambridge Bay on August 29th. Ms. Aitaok organized a cultural camp that included Inuit throat singing, displays of traditional dress, and bannock to eat. She also provided an arts and crafts fair in the community hall. “This is their big shopping stop, which we are very happy about,” she said enthusiastically. The town was prepared to nearly double its population for a 13-hour period, and Ms. Aitaok had everything precisely organized to move the 1,000 or more visitors through during the stopover.

Ms. Aitaok echoed the enthusiasm for the Crystal Cruises organization expressed by Prof. Byers. They were planning to employ a local Inuit guide to explain indigenous traditions, with the guide also attempting to elicit pride among the locals for their own ways. “Crystal’s done everything right,” Ms. Aitaok said. “They’re setting a high standard that I don’t know if other ships will be able to match.”

The third Inuit community the ship is scheduled to visit is Pond Inlet on September 5. Pond Inlet is located on the northern end of Baffin Island and has about the same number of inhabitants as Cambridge Bay—almost 1,600 people. Like Cambridge Bay, it has hosted numerous visitors over the years. The exponential growth of tourists—coming at one time in one huge ship—may or may not have a severe impact on the Inuit. It is not clear yet.

Okalik Eegeesiak, the Chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, told the Guardian reporter, “far too many people will be descending suddenly into these communities and bringing far too much garbage with them. These places lack the infrastructure and the training to deal with the incredible numbers of people that will start arriving on these boats.”

She added that a major issue for many Inuit is that they still rely for their food on what they can kill and catch in the waters around them. The food chain is threatened by global climate change, which is exacerbated by the huge carbon imprint of large ships. With the melting of the Arctic ice, cruise ships may be able to come through the Northwest Passage, but the bottom of the food chain can be harmed by them. Mass tourism is only likely to make the food problems worse, some Inuit maintain. Ms. Eegeesiak stressed her point: “It is not just the communities we need to worry about when these great boats arrive but all the wildlife of the region.”