An odd story appeared in a reputable Indian newspaper at the beginning of last week alleging that the Kadar have deeply rooted superstitions about the spirits of their dead. The newspaper account was based on supposedly reliable government agency information, not on a reporter’s speculation.

The essence of the story was that staff members of the Kerala Institute for Research Training and Development Studies of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (KIRTADS) was going to employ exorcists to clear out the spirits of the deceased from the houses of dead Kadar. S. Bindu, the Director of KIRTADS, told the reporter from the New Indian Express that the Kadar “believe once a family member dies, their soul continues to stay in the house, making it a haunted one.”

Ms. Bindu added that the tribal people, when they used to live in temporary huts, would simply dismantle them and build new ones after an occupant died. But despite the fact that the government has built brick and mortar homes for the people as part of their community rehabilitation projects, the Kadar families still don’t want to continue living in a dwelling after one of them has passed away.

She said that the officers in her agency have tried talking the people out of their superstitious beliefs but with little success. “We think the tribals might have such traditions. Anyway, we have to come out with a solution to make them stay in their houses,” the official said. The community in question is the Pathipara settlement in the Kerala town of Kodencherry. Seven houses in the settlement have been abandoned for fear of the ghosts of the deceased.

Ms. Bindu, working with the government of the district, has prepared a plan to conduct exorcism rituals in order to rid the homes of the Kadar, Paniyas, and Kattunaykars in Kerala from the spirits of the dead. Hopefully, the living will then be able to continue to dwell in them. The government will do a detailed study of the issue since a lot of funds have been invested in constructing new housing for the indigenous people.

“Unless we find a solution, the housing project for tribals will not benefit them because already a lot of houses have been abandoned by tribals who either make new huts or shift to houses of relatives,” Ms. Bindu said.

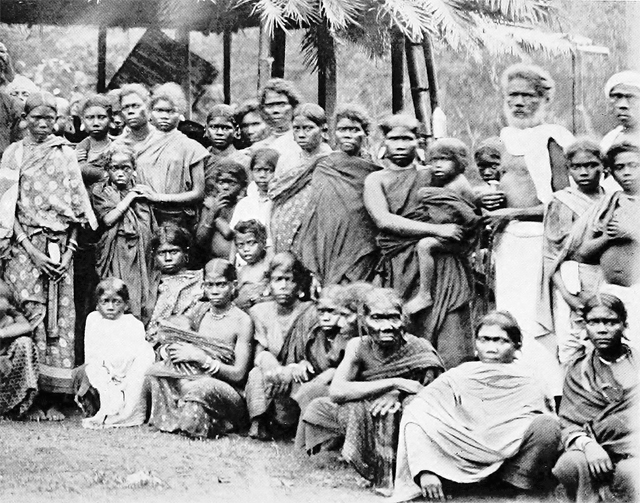

Whatever the literature about the Paniyas and the Kattunaykars may say, the standard ethnographic works about the Kadar appear to question, or in fact to flat out contradict, the understanding of the officials in KIRTADS about the traditional beliefs of the people. Thurston (1909) provided a lot of details about their funeral customs. He wrote that the Kadar conduct simple ceremonies for their dead. They put new clothing on the body, tie it in a mat, place some old clothes of the deceased in the grave and put the corpse on top of them. They believe that the dead go to heaven, though Thurston pointed out that they were reticent with him about their burial customs. Thurston mentioned a European story that the Kadar eat their dead, a legend that, he argued, was completely false.

Thurston continued that they conduct final funeral ceremonies, depending on the financial resources of the family, as soon as eight days after the death for those with sufficient means or as long as a year afterwards for those who have to save for the event. But on the morning of the chosen day they bring cooked rice and other foods to the hut of the deceased and place it in all four corners in order “to propitiate the gods, and to serve as food for them and the spirit of the dead person (p.24).”

The Kadar community, particularly the friends and relatives of the dead person, then gather, cry and lament the passing of the deceased, make speeches about the qualities of the person, and after an hour of this they go into the hut of the dead. There, the oldest man prays to the gods and turns to the heaps of food in the corners of the hut—rice, vegetables, and meat. Everyone takes a pinch of food and tosses it in the air as an offering to the gods and then begins eating. So much for dismantling the hut to exorcise the spirit of the deceased.

A chapter on the Kadar by Anantha Krishna Iyer (1909) described the burial customs somewhat differently than Thurston. He did make one point that was relevant, however. He noted that the Kadar bury their dead in distant burial grounds and never visit them afterwards “for fear of ghosts which may haunt their houses and torment their children (p.13).”

A more recent, standard ethnography of the Kadar by Ehrenfels (1952) provided the most effective answers to questions about their traditional religious beliefs and practices; he addressed the question of the disposal of the house of a deceased person. In the course of discussing their inheritance of property, he wrote, p.150, that neither the houses nor the leaf shelters of the deceased will be destroyed after the owner has died. Some or most of the family will continue to live in the dwelling and the family will cooperate in repairing and maintaining it, with the most active and decisive member of the family organizing the repairs.

These discrepancies between the ethnographic accounts and the beliefs of the people today might be explained by a number of circumstances. Possibly the Kadar in the Pathipara settlement have absorbed beliefs from their neighbors that vary considerably from those of their ancestors. It is also possible that regional variations might explain the differences. Contemporary news reports usually update the beliefs and practices of the peaceful societies as described in the literature—the purpose of these news and reviews. It is curious, however, to encounter a news report about an indigenous custom that so directly contradicts the observations by earlier anthropologists.