Numerous Batek people living in Kuala Koh say that they still prefer living nomadically in the Malaysian forests rather than in permanent houses. Several were interviewed by Aimuni Tuan Lah for a report published in the Malay-language newspaper Utusan Malaysia last week.

Over 60 Batek families move about the forest of Kuala Koh, also known as the Taman Negara National Park, subsisting in traditional ways. They gather forest products such as rattan, roots, and herbal medicines and they hunt for game. JAKOA, the government agency in charge of development for the Orang Asli, the aboriginal people of Malaysia, has provided 13 houses for the Batek. It appears as if the houses are in Gua Musang where the story was bylined. But the Batek don’t want to live in them. They prefer to live in the forest in huts made of traditional woods and leaves, particularly the leaves of the nipah palms which are used to cover the roofs.

The reporter interviewed a 70-year old man, Daun Kepayam, who told her that the people especially appreciated living in huts made from plant materials. He said that most of the Batek didn’t like the government-provided permanent houses because they did not cool off at night the way their forest huts did. In the words of the Google translation, he said, “We prefer to sleep on the floor with bamboo and wood as a place to lie down with family members.” He added that they rarely travel to the city but sometimes city people do visit them to give them clothing and food.

Salman Daun, a 40-year old man, said that he has lived in Kuala Koh for a year. Before that, he moved about searching for food in a forested area near the town of Jerantut in Pahang. When he returned to the Gua Musang area, it took him three days to walk to Kuala Koh. But then it only took him two days to erect his hut by himself. “We prefer migration to find forest resources to sustain life,” he said.

Aimuni Tuan Lah, the reporter, quoted a third Batek man, Pikas Langsat, 55, who told her that they obtain money by selling roots and herbs and they use the funds to buy rice. He complained that they have to find the minor forest products in remote locations since the forests closer to where they live are threatened by the development of oil palm plantations.

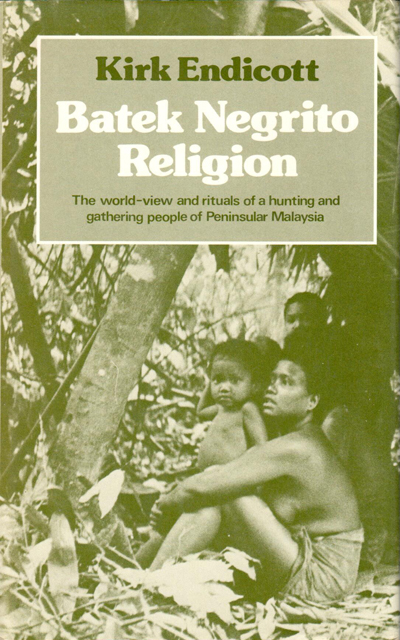

In his book Batek Negrito Religion, Kirk Endicott (1979) explained that the people identified very closely with the environment of the rain forest, sometimes even calling themselves “forest people (p.53).” It was their only preferred home, and to judge by the news story last week, it still is. They believed, Endicott wrote, that living in the forest is part of the natural order as established by the superhumans. While individuals might leave the forest for varying lengths of time, if all the Batek left, the superhumans would destroy the world. The people were not afraid of the forest—they felt secure living in it, comfortable being part of it. Unlike many forest-dwellers, the Batek did not even separate themselves symbolically from the surrounding woods.

In his book Batek Negrito Religion, Kirk Endicott (1979) explained that the people identified very closely with the environment of the rain forest, sometimes even calling themselves “forest people (p.53).” It was their only preferred home, and to judge by the news story last week, it still is. They believed, Endicott wrote, that living in the forest is part of the natural order as established by the superhumans. While individuals might leave the forest for varying lengths of time, if all the Batek left, the superhumans would destroy the world. The people were not afraid of the forest—they felt secure living in it, comfortable being part of it. Unlike many forest-dwellers, the Batek did not even separate themselves symbolically from the surrounding woods.

A few years later, Endicott (1983) explained part of the reason for the fervent attachment by the Batek to their forests—and, as a corollary, to their peaceful lifestyle. He argued that their peaceful, non-aggressive, passive nature as well as their attachment to the forests can be directly traced to their being the object of violent slave raids by Malays in the 19th century. They learned from those experiences that flight into the forests for the most part provided the only possibility of survival, while fighting against the Malay slave raiders was generally hopeless and brought on injuries or death.

Whatever else the forests provide to the Batek, it is clear from the news story last week that they are still highly important to the people.