A village in the rural Isaan region of Northeast Thailand has been haunted by malevolent ghosts, the villagers believe, but fortunately they’ve been able to get help in exorcising the harmful spirits. An article last week in the South China Morning Post explained how the Rural Thai villagers came to believe their community was haunted—and what they did about it.

The residents in the 370 households in Ban Na Bong, a village in Nong Kung Si District, Kalasin Province of Isaan, hired a ghost catcher after a series of unexplained deaths alarmed the people that ghosts were causing the evil. The head of the district government, Wirat Tatcharee, on Monday last week got involved, asking health and livestock officials in the province to do health checks on all the humans and animals living in the afflicted community.

Mr. Wirat said that he wanted to boost the morale of the villagers, who were stressed by the perception that malevolent spirits, which they call phi pob, had invaded. The journalist explained that a phi pob is a form of ghost in Thailand that eats raw meat, particularly the internal organs of people and animals that it has invaded, thus killing them.

In the last few weeks, since the end of October, the people of Ban Na Bong have seen two men as well as several animals—buffaloes, dogs, and cats—die mysteriously. The deaths could only have been caused by phi pob. The people paid 124 baht (U.S. $3.74) per household to hire prominent ghost catchers to come into the village and catch the evil spirits.

The rite the ghost catchers, plus a monk and 20 aides, performed at the village at the beginning of last week took over two hours to perform. The ghost catchers felt they had caught 30 phi pob and forced them to move into bamboo tubes, which they had then burned. The villagers all felt better after the work of the ghost catchers had been completed. They surrounded their houses with strands of holy threads to scare away any remaining ghosts. District officials and police attended the ritual to make sure it went smoothly. The district chief said afterwards, “Everything went fine. I saw smiles on their faces.”

However, the following day, another man died suddenly in the village. But the district police said that there was no indication on his body of any assault and the district hospital confirmed that analysis. He had died of heart failure. His mother also said that her son had not died of an attack by a phi pob.

Many scholarly works on rural Thailand discuss the popular Thai beliefs in spirits and ghosts, indicating that the folklore has been important in Rural Thai culture for a long time. John E. DeYoung (1955) wrote in his book Village Life in Modern Thailand that the spirits, which he called pi, were an essential part of the lives of the peasants and were frequently propitiated. Those spirits existed in many different forms, such as the spirits of the dead, the spirits of trees, the spirits of houses, and the spirits of a wide range of natural objects.

If the spirits were not effectively propitiated, he indicated, they could become evil. “Even the spirit of a dead parent can become a thing of evil,” he wrote (p.143). The author said that what he called “spirit doctors,” or spirit practitioners, were found in most rural villages. The villagers, particularly the ones in remote areas, went to them to have evil spirits exorcised out of people who had become ill. DeYoung described in some detail the practices of the spirit doctors in driving the evil pi out of sick people.

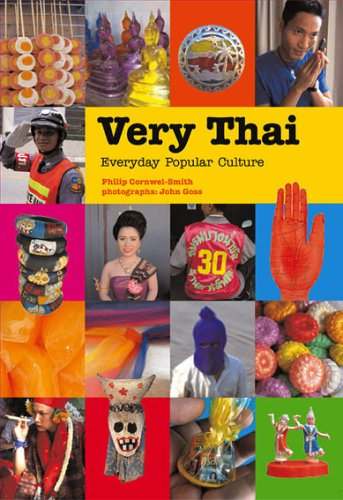

But Cornwel-Smith (2005), in his engaging and colorful book Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture, provided one of the best explanations of the place of superstition in Thailand’s society today. He explained that a gap has developed between the frazzled modern Thai people and the dwindling number of Buddhist monks. Contemporary Rural Thai, when faced with serious issues, frequently turn to the spirit world in the belief that that works better than the accepted virtues of Buddhism. The Thai will substitute the proven, practical value of the spirits for the wisdom of the holy monks in the temples.

But Cornwel-Smith (2005), in his engaging and colorful book Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture, provided one of the best explanations of the place of superstition in Thailand’s society today. He explained that a gap has developed between the frazzled modern Thai people and the dwindling number of Buddhist monks. Contemporary Rural Thai, when faced with serious issues, frequently turn to the spirit world in the belief that that works better than the accepted virtues of Buddhism. The Thai will substitute the proven, practical value of the spirits for the wisdom of the holy monks in the temples.

An amazing 80 percent of the Thai people take the supernatural seriously and accept the stories of those who have experienced visitations. When dogs howl at night, they are seeing ghosts. Even sophisticated Thais, while they may discount superstitions, will still assuage the spirits “just in case.”

There are over 40 different types of Thai ghosts, with variations in different regions of the country, and each incorporates a moral message. The evil spirits that possess living beings, which Cornwel-Smith called phii porb rather than phi pob, are the souls of the greedy; they are represented typically by ugly old crones, or witches. They tear apart livestock during the night.

Modern exorcisms are normally nonviolent affairs that are held to compassionately re-balance the energy in a community, to correct wrongs and to begin things again. They are conducted by lay spirit doctors or unorthodox monks. Cornwel-Smith noted that one held in 2003 in a village near Udon Thani, a city in Isaan, attracted 2,000 people. The monk and the teams of ghost catchers absorbed much of the budget of the village but after three hours they had caught 39 ghosts blamed for the premature deaths. The monk told the author, “Nine of them are strong willed phii porb [while] the rest are other ghosts and stray spirits (p.180).”

As Thailand has modernized, the Rural Thai people have increasingly sought answers from occult authority figures rather than from members of the social hierarchy. Belief in the phii suggests that social messages are welcome. Ghost stories impart the worth of living a healthy social life, the value in avoiding greed, the benefits of good hygiene—and the importance of not staying outside after dark. Ghosts are still present today in Rural Thailand and their messages have been integrated into the popular Thai culture of movies, television soap operas, and comics.