Young Ladakhis are coping with the changes that are sweeping their region by struggling to retain their identities, yet they are accepting new ways of looking at economic, political and social issues. Rinchen Norbu Wangchuk last week focused a perceptive analysis on young people who are seeking to maintain their Ladakhi traditions—and yet keeping up with modernizing trends as well.

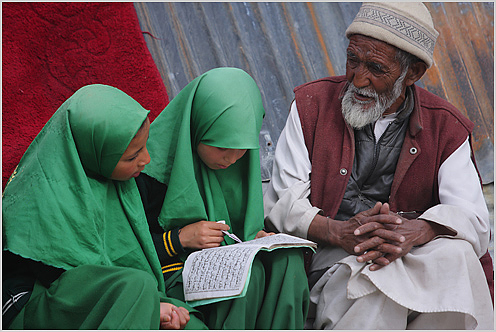

The Ladakhi youth are trying to negotiate a worldwide youth culture but at the same time many want to preserve their ethnic identities, according to Professor Sudha Vasan at the Delhi School of Economics. They are torn by personal attachments to the different cultural identities in the Leh and Kargil districts, where religious authorities have politicized their societies. The young people are more or less forced to obey the dictates of their religious leaders and to accept their Buddhist (in Leh) or their Shia Muslim (in Kargil) ways.

Prof. Vasan wrote that the Buddhist and Muslim leaders of both districts have become increasingly competitive and exclusionary against what they see as minority faiths. She indicated that the focus on youth culture and identity in Ladakh has developed, in part, due to this religious divide between the two groups. “While there has been no communal violence in Ladakh since 1989, cleavages along religious lines remain,” she argued. And to emphasize: the Ladakhi youth, the future of the region, are required to adhere to the religious boundaries that their elders maintain for them.

For example, Murtaza Ali, a graduate student, said, “Growing up in Kargil, my parents compelled me to study the Quran, even though I wasn’t particularly interested in it. At home and school, it was my Muslim identity that took precedence.” But when he attended college in Delhi, the strictures mostly fell away. He was able to hang out with other Ladakhi students—Buddhist, Sunni Muslims, whatever. Sometimes things got a bit heated but evidently the students were able to work out their differences.

At the same time, class differences are being exacerbated by the very fact that some families can afford to send their children off to expensive schools, colleges, and universities in the cities of India while others cannot. Kids from families that cannot afford a higher education are left with the option of taking jobs in the tourism industry or perhaps of joining the Ladakh Scouts, a military regiment.

When the young adult students return to their home communities during holidays, they may be seen as role models for other young people—or as arrogant for appearing to show their superiority. A prominent Buddhist leader expressed dismay that some of the returning educated students seem to be forgetting their own culture—many can no longer even speak Ladakhi. “Why are they ashamed to express their tradition? This is unfortunate,” he said.

A woman named Stanzin Dolma said that while Delhi was a lot of fun, there is a hostile work environment against women in the huge city. She complained that the high cost of living in Delhi also worked against her. She does not have as much income in Ladakh, but life is somewhat easier for her than it was in Delhi. But she has also suffered discomfort back in Ladakh. She said she feels disconnected from other Ladakhis and since she now speaks Ladakhi with a bit of an accent, people are critical of her. She concluded, “There is little that binds me to my people back home.”

The journalist, Wangchuk, observed that many Ladakhi young people studying and working in cities such as Delhi feel alienated from both India and Ladakh—but at the same time they identify with both of those disparate cultures. In essence, they feel they belong to both the traditional culture and the modern one, but it is hard to reconcile the differences.

Another factor at work among the outsiders in the big cities is that the Ladakhis and the students from Northeast India are all Himalayan and, to the Indian people in general, they all look alike. So the Ladakhis and the people from Northeast India hang out together. “We are both minorities in this city, [so we] tend to stick up for each other,” said Nafisa Sheikh, a recent graduate of Delhi University.

Dislocations of the younger generation are not solely the province of students in big cities. Tsering Dolkar, a young Ladakhi woman who studied at a boarding school in South India, has returned to Leh to build an eco-friendly resort. The youthful entrepreneur is frustrated by the ignorance of many Ladakhis about their traditional mud-brick construction techniques. She wants to build sustainable buildings but is saddened that Ladakhi contractors and construction workers are not even aware of the distinct advantages of using compressed mud bricks and traditional toilets in their new buildings.

Another woman, Kunzes Wangmo, who just completed a master degree program from Panjab University in Chandigarh, expressed a more hopeful perspective. She said it was not possible to resurrect the culture of Ladakh from the last century, but it was possible to insist on an acceptance of minority cultures in Ladakh and to support “an ecologically sustainable economic model rooted in tradition.” These factors, in time, will help build an identity of self and an acceptance of belonging, she argued.

Wangchuk concluded the essay by advocating “a greater engagement between young Ladakhis and their roots.”