Two sailors on a cross-Pacific voyage kept running into very difficult sailing conditions so they decide to head for Ifaluk Atoll in search of better winds. Claude Appaldo and Tom Zydler sail into the Ifaluk lagoon in the western Pacific after a voyage across the ocean from Panama that took many months to complete. The lead author, Mr. Appaldo, complains in a blog post in Cruising World about the contrary head winds, giant thunderstorms, and sloppy seas they encountered across most of the Pacific Ocean. They averaged only 4 knots on their trip.

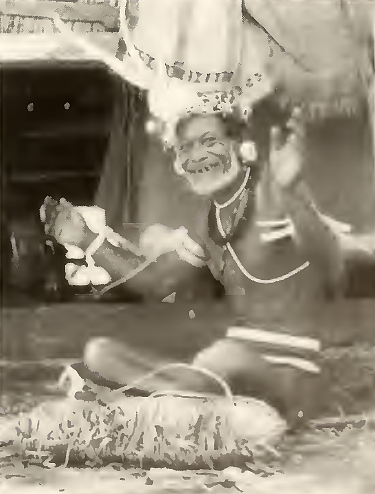

As sailors, they naturally focus on the sailing and fishing of the Ifaluk men. Appaldo writes that the Ifaluk fishermen use traditional vessels called proas, boats with outrigger hulls. Three days after they reach the decision to stop at Ifaluk, they spot the sails of a dozen vessels and head into the Ifaluk lagoon. They call on a chief, pay for their anchorage and landing privileges, and start to wander around the island—“a scene from the dreams of South Pacific,” Appaldo writes.

They notice the outrigger proas lined up along the edge of the lagoon—15 large boats and at least 10 smaller ones. The Ifaluk men describe how they build the boats with timber from breadfruit trees and sew the pieces of the hull together with line, for they have no iron fasteners. They caulk the boats with breadfruit sap and coconut husks and make ropes out of coconut fibers. Sometimes they are gifted with synthetic lines and even with used sails by the owners of visiting yachts.

Mr Appaldo requests the opportunity to go sailing with the Ifaluk, so he is cordially welcomed to leave with them at 4:00 AM the next morning. He finds the men hanging out in the canoe house fabricating fishing lures out of the fronds from coconut palms. They put the observer on the outrigger as they head out to sea in a proa and soon they are in the midst of 20 to 25 knot winds and spray from a thunderstorm.

The fishermen spot some feeding sea birds that the author is not able to see. They catch three tuna on their four trolling lines and head back into the lagoon. Three of the boats cut through the channel side by side, the men talking and laughing, all at ease with their boats and their way of life.

The author is moved by the acceptance by the Ifaluk men of their lives and how little in the way of material goods they need to stay happy. It is such a contrast to all the devices and stuff they have aboard their own vessel, with its fiberglass hull, diesel engine, Dacron sails, stainless steel rigging, stove, shower, fridge, and so forth. He searches for things to share with the Ifaluk men. Unfortunately, he does not have a spare sail but he does have an extra 100 feet of ¾ inch braided rope to give them. He appeals to other sailors who have extra sails to contact him. Also, since there are no sewing machines on Ifaluk, the islanders could use gifts of needles and thread. He provides a contact link at the end of his blog post.

Richard Sosis, an anthropologist who did field work on Ifaluk Island in the 1990s, discusses the traditional culture and values of the islanders in an article that is available on the HRAF website. The major point of his article is to provide descriptions of fishing by Ifaluk men. The author concentrates on fishing—men’s work—because he was not allowed to observe the Ifaluk women working in their taro patches.

In the course of his article, much of which focuses on the methods of Ifaluk fishing and the ways they share their catch, Sosis indicates that Ifaluk is still very much cut off from the mainstream—the atoll has no roads, no motor vehicles, and no electricity. The bottom line of the Sosis visit: the chiefs, the unquestioned authority figures on the island, are strenuously maintaining their traditions. While Mr. Apppaldo does not say so directly, it appears from his blog post as if not much has changed.