Out of the 82 communal conservancies established by the government of Namibia, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy of the Ju/’hoansi San is without doubt the most prominent. The nation’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) has, for 20 years, awarded Nyae Nyae the largest hunting quotas of all the conservancies in the country. The success of their model has been widely touted, but John Grobler decided to ask, how well is it really working? His 5,700 word answer was published on Tuesday last week by the distinguished environmental news website Mongabay.com.

Grobler provides many details about the Ju/’hoansi, their hunting tradition, and the management of the conservancy. In 2018, he writes, Nyae Nyae received permits to harvest over 1,300 birds and animals, including nine buffalos, nine elephants, seven elands, three leopards, one giraffe, and many smaller animals. According to Stephan Jacobs, a prominent big-game hunter and guide—and the individual with whom Nyae Nyae contracts to handle its allotment of game permits—the conservancy is well-known among trophy hunters as the best hunting area in the world for elephants.

The conservancy model that Namibia touts as beneficial for both the local communities and for wildlife gives the conservancies the option of selling most of their allotments to big game hunters for cash, as Nyae Nyae does with Jacobs. Those business owners then sell trophy hunts to rich international people who will pay very large sums of money to stay in lodges or tent camps and have a chance to bag a highly-desirable prize, such as an elephant.

While the San people living in the Nyae Nyae have other sources of income, such as gathering and selling Devil’s Claw tubers, trophy hunting provides 86 percent of the total income of the people—about $120 is shared annually to each of its 1,500 members. The income from trophy hunting also allows the conservancy to have an office and to provide a small salary to 27 permanent staff members. The funds also help provide both water to communities and basic social services for the people.

In theory it should be a successful model—local people controlling their destiny, getting the money they need from the local resource, yet managing it well so that the resource (the wildlife) doesn’t unduly suffer. Well-managed trophy hunting is the key to successful development and conservation, the reasoning goes. The author finds that it is not working as well as the hype of its promoters would have us outsiders believe.

The management strategy was instituted enthusiastically by the new government of Namibia after independence from South Africa in 1990. It was a bottom-up management approach called Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) in which local people control the hunting and stand to benefit from wise harvesting of the resource. With the support of WWF and financial assistance from USAID, the Ju/’hoansi started forming the first communal conservancy, Nyae Nyae, in 1996.

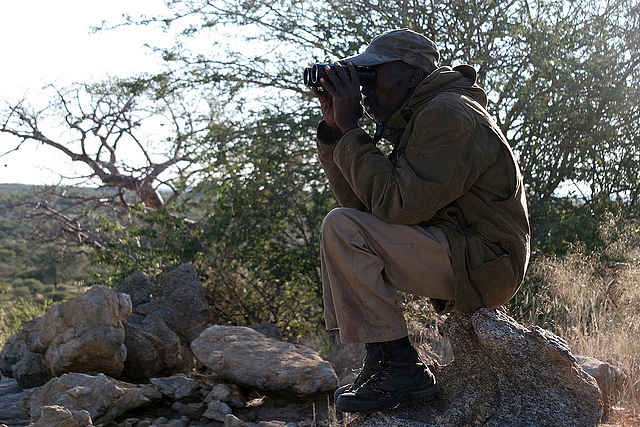

Grobler spent a lot of time interviewing Kiewiet, an elderly but well-known Ju/’hoan hunter, plus other Ju/’hoansi and various officials during a week-long visit to the conservancy recently. He relentlessly asks questions of everyone to see how well the oft-touted hunting strategy used by the conservancy and promoted by the government is really working. How much are the San benefiting from the hunting program and how well are the wildlife doing?

The writer builds his case for local involvement in decision-making. He visits a cultural center built in the middle of nowhere. Funded by foreign aid money, four buildings have sat abandoned since funding dried up in 2014, their roofs removed by local people who prize the galvanized sheets for their own homes. But why was the cultural center started in the first place? No one seems to know. Perhaps local people should have been consulted.

But Grobler notices more than just the absence of tourists in the area. He also notes the almost complete absence of wildlife. The major signs of animal life are the droppings of cattle. Other than a few sand grouse and harlequin quails drinking from small spots of water in post holes and a duiker that dashes off when their vehicle approaches, there is no wildlife to be seen. The area in the conservancy that he is visiting has been designated as free of farming and livestock—a core conservation area where the game is supposed to be left undisturbed.

Dunny Coma, his guide provided by the conservancy, tells him that getting the owners of the cattle to remove their herds is a difficult issue. They live in Tsumkwe, the town that serves as the center for the Nyae Nyae, and claim they can’t control the grazing habits of their cattle. Some of them are well-connected people who have fenced, illegally, significant tracts of land. The one game warden was also farming cattle so no one seems willing to try to enforce the laws protecting wildlife from the livestock.

Grobler devotes space to his discussions with Kiewiet, the elderly San hunter who lives in the village of Makuri, about 12 miles from Tsumkwe. He tells the author that he saw flaws in the approach that John Marshall, the famed film maker, was making in his approach to the future of the Ju/’hoansi. Marshall advocated that his San friends should give up their traditional hunting and gathering and convert their economy to herding cattle. Kiewiet observed that the income from the livestock was quickly being converted into alcohol. But the hunter says he saw the value to the community-based CBNRM approach.

Now in his late 80s, Kiewiet recalls visiting the early prototype of a community-based approach for game management in the Caprivi Strip, about 300 miles northeast of Tsumkwe in the early 1990s. Giving the local people control of their game resources struck him as a very appropriate approach, especially after decades of apartheid-style management under South African rule. “We live with [wild] animals,” he tells Grobler in fluent Africans, so “to us the animals are like our cattle.” He became a promoter of the CBNRM concept.

Then, when the Nyae Nyae Conservancy was formally set up by representatives of the villages within it, Kiewiet became the first chair of the conservancy management committee. But, he argues to the author, troubles began in 2009 when the office of the conservancy was moved from Baraka, a village which is close to the border with Botswana, to the regional center, Tsumkwe.

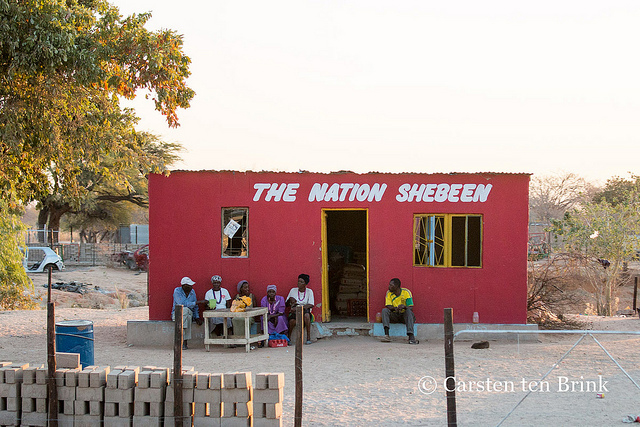

The move fostered a change to a cash culture and the unraveling of the communal character on which the conservancy was founded. Everyone needed money for everything, it seemed. And the local social scene in Tsumkwe shifted to the shebeens, the cheap bars. If you couldn’t come up with the cash to pay your debts for the alcohol, the owners of the bars would gladly accept your cattle as payment.

Grobler analyzes many issues related to the community conservancy model exemplified by Nyae Nyae. A brief review can only touch on a few of them. For instance, the communal model calls, in part, for the distribution of meat gathered from the game animals shot by the foreign hunters. But elephant meat is especially tough to chew and the elderly informants of the author, such as Kiewiet, protest volubly that they have a hard time eating the elephant meat they receive.

The author also expresses a lot of concern that the allocation of permits by species is not effective. Jacobs, the big game hunter and holder of the Nyae Nyae contract to manage the hunts by foreign tourists, focuses on his business model—he can charge a hunter $50,000 for a couple weeks of elephant hunting but only get $500 for a gemsbok hunt. In a subsequent phone call, he blames the problems of inadequate numbers of animals on the Ju/’hoansi themselves. They are “poaching the hell [out] of everything,” he tells Grobler.

The MET, which is supposed to be managing the whole operation to protect the resource—the animals—is unable to do its job properly. It employs one warden, stationed at Tsumkwe, to do such things as monitor the game counts at 19 waterholes spread out over about 9,000 square kilometers, a logistical impossibility, the author observes. The future of the Ju/’hoansi San may be at risk.

And so on he goes, applauding the intent of the community hunting preserves and the goal of local management but undercutting the self-promoting hype. It’s not working perfectly and by pointing out the imperfections his analysis might help the Namibians and the Ju/’hoansi to improve the local model and star performer, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy. Mr. Grobler and Mongabay.com should be applauded for publishing this excellent report.

Grobler, John. 2019. “It Pays but Does It Stay? Hunting in Namibia’s Community Conservation System.” Mongabay.com, 26 February