On March 18, Matteo Fagotto published an article in a news magazine that was partly a travel piece about his homestay with a Lepcha farmer in the Dzongu region and partly an investigation of organic agriculture in all of Sikkim. He points out that the famed organic farming in Sikkim has been championed vigorously by his homestay host.

The author notes that Sikkim is the first completely organic state in the world. Pesticides and chemical fertilizers were phased out in the small state in northeastern India in 2003 as farmers were trained to use organic methods in their work. Wildlife and bee populations have increased in Sikkim as a result.

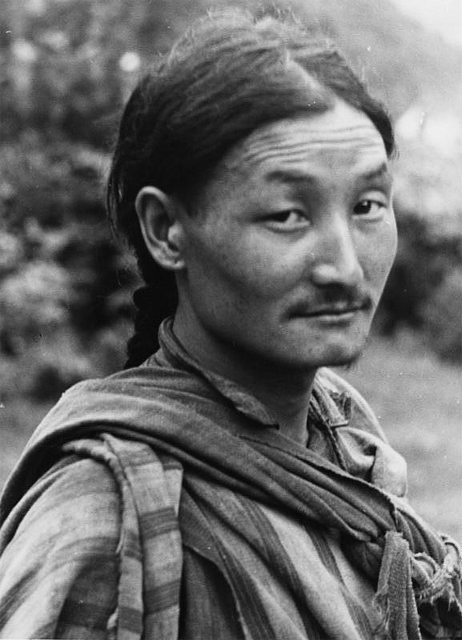

Tenzing Lepcha, Fagotto’s homestay host for a week, is a 39-year-old farmer, environmental activist, and proponent of preserving the earth, which he and many of his neighbors consider to be sacred. As Mt. Kanchenjunga rears up above the morning mist surrounding the Dzongu village, Tenzing tells the author, “This mountain is sacred to all Lepchas. We believe we were created by its snow. Whenever one of us dies, anywhere in the world, his soul travels back to the mountain.”

Tenzing felt compelled in 2008 to leave the comforts of urban life in Kolkata and, returning to his roots in the Dzongu, began working on his farm. And like some others in the neighboring villages, he opened his home to visitors. The author enjoys the daily rhythms of farm life, such as sharing warm cups of milk tea after spending time harvesting and husking rice. He visits hidden waterfalls, hot springs, and sacred Buddhist ponds.

On Sunday morning, Tenzing leads his guests on a two-hour hike up a steep path to a clearing in the forest where a wedding is taking place. While a priest blesses the bride and groom with burning incense and ghee, girls in colorful dresses serve drinks and food to the dozens of guests gathered in the single-story, red and blue house in the clearing. The guests wait their turns to give silk scarfs to the newly wedded couple. Then they all leave the house to join circles of dancers in the forest clearing.

After dark, Tenzing leads his homestay guests back down to his house where everyone gathers at the fireplace and drinks traditional beer served in hollow bamboo logs. Tenzing has topped the beer with a few grains of rice, a symbol of respect for his guests. Everyone shares stories and a delicious, entirely organic, dinner of rice, greens, and soups.

When asked about the future, Tenzing admits that he and his colleagues cannot tell the upcoming generations what to do. “What we can do,” he says, “is show them a path that was created by our ancestors, and which my fellows and I decided to follow.” The path created by the ancestors was, of course, veneration for the sacred mountain and love for the land, expressed through the use of organic farming techniques.

Fagotto repeats one of his central arguments: that Sikkim led the world by becoming, in 2016, the first completely organic state on earth. The goal of the people was to build a healthier environment for the human and the natural inhabitants of the eastern Himalayas where the state is located. All 76,000 hectares of farmland in Sikkim are now certified as organic and free of imported chemicals.

The author concludes that humans are not the only ones to benefit from the popular decision to go organic. Not only are local authorities recording increases in wildlife and bees, but researchers at Sikkim University have noticed surging numbers of butterflies in cultivated areas. These improving numbers show that the switch back to traditional agricultural techniques may be best for the land and all its living inhabitants.