Although Babar Afzal comes from the city of Jammu, he is devoting a lot of energy to saving and revitalizing pashmina goat wool production in Ladakh. He founded the Pashmina Goat Project in 2012 to address the concerns and promote the interests of the goat herders in the Changtang region of Ladakh, near the southeastern border with Tibet.

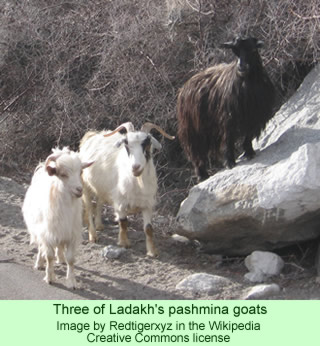

The wool from the goats, which live in both Ladakh and Tibet, is six times finer than human hair and has been a highly prized export for centuries. It is gathered by the goatherds living in the high mountains, exported by middlemen, and fabricated in city factories into a highly prized wool called cashmere. A single scarf on the international market can cost several thousand dollars.

The wool from the goats, which live in both Ladakh and Tibet, is six times finer than human hair and has been a highly prized export for centuries. It is gathered by the goatherds living in the high mountains, exported by middlemen, and fabricated in city factories into a highly prized wool called cashmere. A single scarf on the international market can cost several thousand dollars.

The Changpa goat herders in the Changtang region see little of that money. Most has historically gone to the middlemen and the manufacturers. The middlemen buy the raw pashmina wool for US$40 to $80 per kilogram, then sell it to dealers for five times as much. A 39 year old goatherd named Tsering Dolma tells the journalist writing a story for Time magazine last week that “there’s so much struggle in our lives.” She motions to her three-year old son playing nearby and adds, “Why would we want our children to continue in this trade.”

Babar Afzal, 38, learned of the plight of the Changpas a couple years ago when thousands of their goats died in unusually heavy winter storms. He had left his native city—Jammu, the winter capital of the state of Jammu and Kashmir—in 1996 for a business career in New Delhi. But he returned to Jammu with his family in 2008 and started new business enterprises, such as restaurants that promote local foods and handicrafts.

He became focused on the effects of climate change on the state, and particularly on the Changtang region of Ladakh. He was especially affected by the unusual winter kill in 2012: “The horrific sight of thousands of dead goats and bewildered Changpas haunted me for months,” he says.

So Mr. Afzal started the Pashmina Goat Project, a cooperative that seeks to improve the lot of the Changpa goatherds. He holds workshops to teach them about the consumer market and ways that they can deal directly with international buyers. He also teaches them how to spin their pashmina wool into fabric, thus adding value themselves. They are organizing a knitwear brand called Village Pashmina so they can sell their products directly to consumers.

Sonam Dorjee, a Changpa, reflected on the changes the project is bringing to the Changtang. “If we asked for more money, the traders laughed at us because we had nowhere else to go, [but] now we do.”

Mr. Afzal has also campaigned against the use of machines for spinning the raw wool, and the adulteration of the pashmina with lower quality wool, arguing instead for top quality production and the use of handlooms. Obviously an energetic individual, he organizes fair trade sessions, fashion shows, and other events to promote his obsession. He plans to develop software that will send weather alerts to the goatherds, so they can be aware of storm predictions and better react to changing weather patterns.

Pankaj Chandan, an official with WWF-India, says of Babar Afzal that his “is the first voice speaking up for the poor and marginalized in the Himalayas.” Afzal responds that the Changpa goatherds are not really able to fight the battle on their own—so he has made a cause of helping them.