According to Kachyo, police officers stationed at the entrance to the Dzongu Reserve in Sikkim have hardly any work to do—there is very little crime among the Lepcha people. One of the reasons might be their ancient ceremony, called the thoursu, which is performed to keep the peace among them by appeasing the “quarrel” gods: Soo Maang, enmity of speech, Ge Maang, enmity of thought, and Thor Maang, enmity of action.

However, others have written recently that the Lepcha no longer perform that ritual. Whatever the case, E. K. Santha, a research scholar at Sikkim University in Gangtok, visited the Dzongu Reserve with Kachyo, a Lepcha friend, to gain some impressions of the culture of his society. The author described the visit in a brief article published last week in the prominent Indian magazine Economic and Political Weekly.

However, others have written recently that the Lepcha no longer perform that ritual. Whatever the case, E. K. Santha, a research scholar at Sikkim University in Gangtok, visited the Dzongu Reserve with Kachyo, a Lepcha friend, to gain some impressions of the culture of his society. The author described the visit in a brief article published last week in the prominent Indian magazine Economic and Political Weekly.

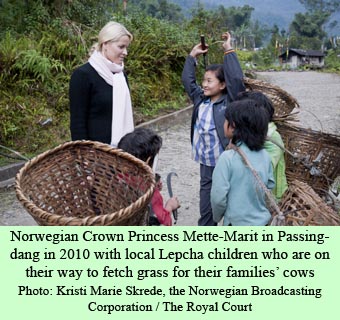

Santha stayed overnight at the home of Kachyo and his family. They live in the hamlet of Passingdang, four hours by rough roads from Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim. Kachyo’s sister-in-law, with help from the children, prepared dinner with vegetables they had picked from the family gardens.

While they visited, Kachyo told Santha about his ancestors, who were shamans before the Bhutias brought their Lamaism into Sikkim in the 17th century. The Lepchas, however, retained some of their earlier beliefs. They have numerous gods, whom they call rums, plus various rites and rituals. The gods and goddesses, who can bring pain and suffering into the daily lives of the people, need to be propitiated through proper sacrifices and ceremonies.

A hunting god is placated with a Mutrum ceremony to protect the hunters from attacks by wild animals. A fertility god, Sakyou Sakyourum, protects seasonal crops and vegetables with the help of the bongthing, the Lepcha spiritual leader. Together they help bring about a bountiful harvest. The Lepcha protect their children by praying to Run Si Mung.

The author describes the ceremony performed by the mun, the female priestess, on the birth of a child. Tang Bong Rum, the god of birth, is offered chicken, ginger, beaten rice, and fried fish to help the child have a safe, bright future. If a family has a male baby after already having three or four female children, they might sacrifice an ox. The mun places a drop of chi, the popular local beverage, on the tongue of the baby at the end of the ceremony.

Santha writes of feeling a touch of fear at the approaching nighttime darkness, and the possibility of bears entering the hamlet from the nearby forests. Kachyo and his contemporaries are part of a generation of learners, Santha writes, people for whom the old ceremonies have somewhat less meaning. But the rites and rituals of the ancient ceremonies still have some meaning in the home.

In the morning, the author noted prayer flags fluttering in the breeze, and noticed the maroon robes of a monk hanging on a clothesline. Kachyo’s father, a monk, visits a Lama monastery every morning. Unfortunately, he spoke no Hindi, so the only possible conversations had to take place through Kachyo’s interpretation.

The author and Kachyo prepared for a visit to Gurudongmar Lake, about 17,500 feet above sea level. They roasted popcorn and dug up ginger in the garden, foods which would help them cope with the very high altitude. But the highlight of the visit for Santha was the gleaming view of Kanchenjunga, the third highest peak in the world and the protective deity of the Lepcha people. It dominated the western horizon in the morning sunshine for a short while before clouds obscured the view.