Christmas is a special time of year for the Semai of Kampung Janggap, though the isolated community in Malaysia’s Pahang state lacks some trappings of the holiday found in other countries. An article in the Malay Mail Online on December 24 described the enthusiasm of the Semai, in that one village at least, for celebrating the holiday in their own way.

The reporter traveled to the Semai village, located near the town of Raub in Pahang, by four-wheel drive on the Saturday before Christmas, December 23, to be part of the celebration. Families gathered together to feast and to socialize with one another. The church in the community is run by a missionary group, the Gospel to the Poor; it is one of 37 churches that they run for the Semai and the Temiar, a neighboring Orang Asli (Original People) society.

The service was held in a simple church hall that displayed a mural and a Christmas tree on the stage. The Semai from Kampung Janggap prayed together in Bahasa Malaysia and sang Christmas songs in the same language, led by one of the villagers. People played electric guitars, drums, and a tambourine. Pastor James Lee, a locally-born individual who has volunteered with GTTP for more than 10 years, recited the Christmas story.

After receiving communion, everyone shared a Christmas feast consisting of beef, fish, rice, chicken and a traditional dish called lemang, a glutinous rice cooked in bamboo. (An October news story pointed out that cooking in bamboo is an Orang Asli tradition.) The charity distributed six kilograms worth of gifts to each of the 100 people living in the village. Each person in a family received two kilograms of rice, two tins of condensed milk, sardines, a pack of sugar, and a package of oil.

The reporter spoke with a several villagers. Masani, 27, said that Christmas is a joyful time of year to share with family and friends. Da, 41, said that his two favorite songs are (with titles translated into English) “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” and “The Lord Hangs on a Cross.” He said that the villagers also celebrate Easter but they only receive the gifts in December. Another person indicated that the Semai do not give each other presents, but they do appreciate the gifts from GTTP.

Pastor Moses Soo, the head of GTTP, told the Malay Mail Online that the organization has seven pastors, four from the Orang Asli communities and three from the local Chinese population; they take turns providing services at the churches they run. The services are held daily in different communities but they have a service at least once a week in each church. After each church service, they provide a meal with foods such as meat, fish and sardines.

The reporter mentioned a few of the other Semai communities that have Christian churches run by the GTTP, including Kampung Tual, the largest, with a membership of about 500. The people of that village had already hunted successfully for wild boar two days before and they were preparing a feast to follow their Christmas Eve church service at 2:00 pm on the 24th.

The mention of Kampung Tual as having the largest Christian church among all 37 served by the evangelical group is interesting because the same community was featured in a late November 2017 news report for its innovative community center, the point of which is to preserve intact the Semai language, stories, and traditions among the young people. The point of the evangelists is to substitute their beliefs for the traditional ones held by the villagers.

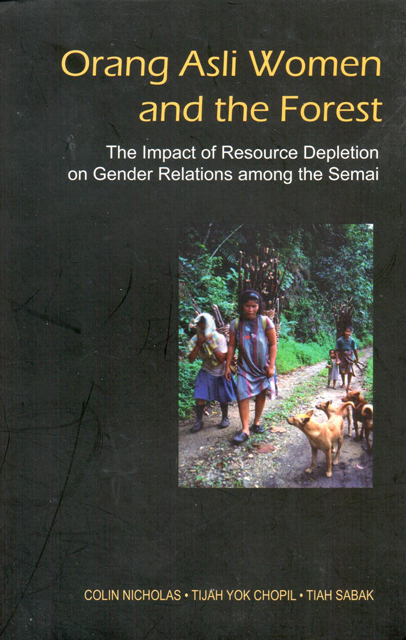

Colin Nicholas and two of his colleagues argued in the 2003 book Orang Asli Women and the Forest (also published in 2010) that Malaysia has a policy of bringing the Semai and the other Orang Asli societies into the mainstream of Malay culture by converting them to Islam. People and communities that convert can expect some financial benefits from the state, but at the expense of their aboriginal culture, which they relinquish in the process. Similar results can be expected, they wrote, from conversion to Christianity, though without the benefits of state financial support.

Colin Nicholas and two of his colleagues argued in the 2003 book Orang Asli Women and the Forest (also published in 2010) that Malaysia has a policy of bringing the Semai and the other Orang Asli societies into the mainstream of Malay culture by converting them to Islam. People and communities that convert can expect some financial benefits from the state, but at the expense of their aboriginal culture, which they relinquish in the process. Similar results can be expected, they wrote, from conversion to Christianity, though without the benefits of state financial support.

The Malaysian government’s attempts to convert the Semai and the other Orang Asli to Islam have been covered by various news stories, such as a review of an article by Kirk Endicott and Robert Knox Dentan in 2005 that described in detail the reasons the government is so keen on converting the people. The Christian evangelists are not out to add numbers to the roles of Malay citizens, as Endicott and Dentan argue about the Muslin missionaries.

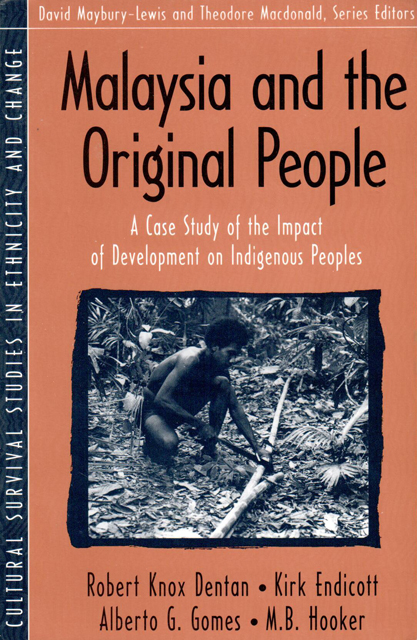

A book by Dentan and three co-authors, Malaysia and the Original People (1997), mentioned that out of an estimated 80,000 aboriginal people in 1993, about 8,000 had converted to Islam. However, a 1984 estimate of the number of Christian conversions was much smaller—about 1,500, primarily Semai in Perak state. It is clear from the Christmas Eve news story that those figures are now out of date.

A book by Dentan and three co-authors, Malaysia and the Original People (1997), mentioned that out of an estimated 80,000 aboriginal people in 1993, about 8,000 had converted to Islam. However, a 1984 estimate of the number of Christian conversions was much smaller—about 1,500, primarily Semai in Perak state. It is clear from the Christmas Eve news story that those figures are now out of date.

But whatever the real figures might be in 2018, the analysis by Dentan et al. (1997) remains quite important. The four authors argued that the primary reason the Orang Asli resist converting to Islam is that they do not want to become Malays—they want to retain their own customs, languages, beliefs, and gods. The authors suggested in addition that some Orang Asli have converted to Christianity in part to escape the pressures from missionaries for Islam, who are supported by the state and who can be aggressive in their proselyting. The government of Malaysia tries to restrict access of Christian missionaries to the Orang Asli communities, they wrote. It is clear from the recent news story that those restrictions are no longer enforced.