The fact that the Semai cherish the foods they prepare from the forest was the topic of a Malaysian TV program and, last week, a brief newspaper article. According to the newspaper report in The Star, chef and TV host Nurilkarim Razha, in his documentary series “The Local Kitchen,” showed viewers an obscure forest fruit called the buah kulim, which has a hard shell but an amazing smell and taste. “It smells like truffles and tastes [like] an explosion of garlic and mushrooms! I can’t believe I’ve never heard of it before,” Nuril said enthusiastically about the delicacy known and used primarily by the Semai.

In the latest episode of his program, Nuril showed viewers the way he creates a forest dish called asam pedas, consisting of yams, buah kulim, and a warm salad of forest herbs. It also features another ingredient, the ginger-flavored kemomok leaf.

The Semai, he observed are aware of the wonderful flavors of these foods, though they may not all be aware of the possible medicinal values of ingredients such as the buah kulim fruits. They are being examined as possible cures for high blood pressure and diabetes. Nuril’s show apparently featured his own creativity as well as the traditional recipes he was following and adapting.

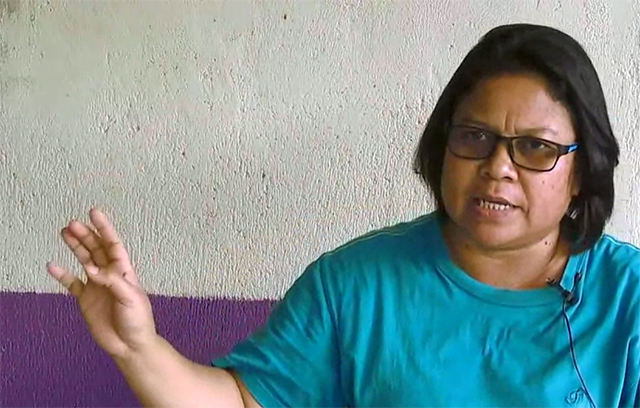

He cooked the dish in the Semai fashion—in bamboo—a tradition of the people. Tijah Yok Chopil, a well-known exponent of Semai culture and defender of their land rights, told the newspaper reporter that cooking by immersing the foods in pieces of bamboo, which is placed near a fire, is a technique that originated from the Orang Asli societies, not the Malays.

“Hopefully, The Local Kitchen will help raise awareness of our culture,” Yok Chopil said, “and people won’t be able to claim our ingredients and methods as their own.” She has been the subject of numerous news reports about her activism for Orang Asli land rights, her struggles for legal guarantees to protect them, and, not surprisingly, an award recognizing her outstanding contributions to Malaysian society.

An article in 2013 about the struggle by the Semai to secure their rights to foods and other products from forests that they consider to be their traditional inheritance quoted Tijah Yok Chopil as urging the national parliament to not pass a bill that would give up their lands to outsiders. Securing Semai land rights has been a major theme of the news stories in this website about that society. Furthermore, foods from the forest, whether hunted game or gathered vegetables, have been a bedrock concern of theirs, as reflected by the major ethnographic works about them.

A few examples should convey that importance, and hence the value of the foods program that Nuril aired recently. Robarchek (1977b) wrote that sharing foods was an essential aspect of Semai culture. Semai women quickly shared the manioc that they harvested when they returned to the village from their fields. Likewise, Semai men shared the fruits of their hunting, fishing, or gathering upon their return home. These patterns were all quite logical since they used to have no way to preserve foods. The single exception to that pattern was that rice was harvested and stored for long periods in the individual houses, but a woman would share some quantities of it with her neighbors as soon as she pounded the husks off.

In a more recent article, Robarchek (1986) linked the Semai beliefs in food sharing with their peacefulness. In fact, the major moral values for the Semai, he wrote, are avoiding violence and sharing food. Food sharing often had little practical value, as one person would share a portion of a harvest or gathering expedition, only to have the recipients share in return portions of the same foods shortly thereafter. But these sharing experiences were, and perhaps still are, extremely important as symbolic, public statements of mutual dependence, nurturance, and the close social ties within the band.

The anthropologist made the same point even more emphatically three years later. Robarchek (1989) wrote that the most important moral imperatives to the Semai were food sharing and avoiding violence. Almost all gatherings opened and closed with statements about the unity of the band, the importance of their interdependence, and the fact that they always help one another.

They were also constantly aware of the dangers that surrounded them from human, natural, and supernatural forces. Thus, mutual interdependence and danger were the two major themes of the Semai world: the individual’s source of security was, and probably still is, the band. The TV show and the newspaper article about it kept the discussion to a basic level—about neat foods. But they covered a topic that resonates with Ms. Yok Chopil and presumably with the rest of the Semai as well.