People who have had the privilege of living in a community that holds an annual town meeting should appreciate stories about the exercise of direct democracy elsewhere. Town meetings are still commonly held in rural New England, often in mid-March—“mud season.”

One year in a small Maine town, for instance, where the snow plow crews did a great job of keeping the roads open during the previous several months, the public works department requested a new truck at the town meeting. The request was approved by the grateful citizens with a round of applause. Elected politicians don’t get between the people and their community’s budget. In that spirit, it is heartening to read that the Ju/’hoansi have a similar, highly democratic, annual budget meeting for their Nyae Nyae Conservancy.

A news report in The Namibian last Thursday provided an overview of the decisions made by the Ju/’hoansi and the budget they established for the conservancy. The report indicated that the conservancy distributed to its 1,493 members about N$2.5 million (US$211,000) in cash benefits, or N$1,700 (US$143.6) per adult.

The members of the conservancy live in 36 villages scattered about the countryside, according to the newspaper report. It went on to quote Xoan//’an /Ai/ae, the chairperson of the conservancy, speaking about their Annual General Meeting: “We have many challenges, but each year at our AGM, we come together to decide how our activities and projects can benefit the community.” The members of the conservancy were allowed to spend their cash windfalls as they wished, but the news report said that many purchased food and essential household items like pots and pans. The funds earned by the conservancy were also directed to the development of water infrastructure and the support of agricultural projects with seeds and equipment.

The conservancy earns a lot of its money through the purchase of permits by foreign hunters to take trophy animals on its lands. According to the newspaper, Nyae Nyae is the oldest of the conservancies in Namibia and it ranks as one of the highest in terms of its earnings. The income allows it to employ 25 local people, from agricultural officers to rangers and craft workers.

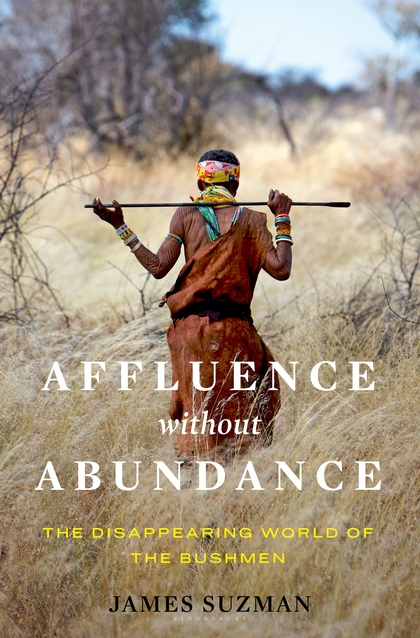

A new book about the Ju/’hoansi by James Suzman (2017), Affluence without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen, provides more information about the budget of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy. Suzman writes that the majority of the money coming into the conservancy derives from permits issued to elephant hunters plus from a variety of government jobs. A few of the workers have interesting positions, such as working as a DJ at the local radio station, but most have routine jobs such as cleaning floors or trimming back shrubbery along roads. People over 60 are entitled to government pensions.

A new book about the Ju/’hoansi by James Suzman (2017), Affluence without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen, provides more information about the budget of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy. Suzman writes that the majority of the money coming into the conservancy derives from permits issued to elephant hunters plus from a variety of government jobs. A few of the workers have interesting positions, such as working as a DJ at the local radio station, but most have routine jobs such as cleaning floors or trimming back shrubbery along roads. People over 60 are entitled to government pensions.

Suzman continues that while the Ju/’hoansi realize the value of money, it appears to them to come from the outside—to which it magically returns at some point. Money, and the things that it buys, exist in a separate sphere from their gift-giving tradition. On paydays, many people do spend their windfalls of cash on alcoholic beverages, accompanied by lots of dancing, singing, eating, and sometimes, violence. The people wonder why some types of jobs are paid more than others. Another questions is, why do prices fluctuate? Further, some wonder where money comes from in the first place. But most of them just accept the fact that their questions don’t have sensible answers so they don’t waste a lot of time attempting to figure out money matters.