Controlling anger is an important attribute of a peaceful society. The Inuit, who do occasionally experience incidents of violence, are nevertheless included in this website because of their amazing strategies for controlling anger. A news story broadcast on the NPR program “All Things Considered” on March 4 adds to the extensive study of the Inuit approaches to anger control by anthropologist Jean Briggs.

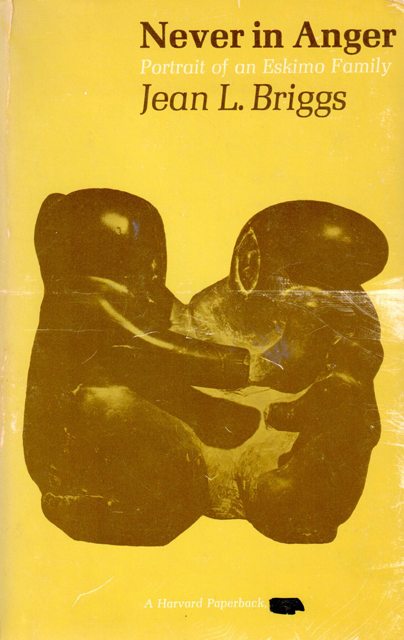

Perhaps the foremost work on the place of anger control in building a peaceful society is Briggs’ fascinating book Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family. The anthropologist found that Inuttiaq, the man in her host family in a remote Inuit camp, was an especially affectionate father toward his four daughters. He never expressed anger toward them and constantly played with and openly showed affection toward them, particularly the younger ones.

Perhaps the foremost work on the place of anger control in building a peaceful society is Briggs’ fascinating book Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family. The anthropologist found that Inuttiaq, the man in her host family in a remote Inuit camp, was an especially affectionate father toward his four daughters. He never expressed anger toward them and constantly played with and openly showed affection toward them, particularly the younger ones.

Other adults in his family praised him for these attributes. One said, “He loves … his children deeply; he is never angry …with them.” Another told their guest the same thing—that since Inuttiaq never got angry with his children, they loved him very much (p.69). A little farther into the book, Briggs pointed out that the Inuit with whom she was living have absolute control over their emotions so that anger never shows through. Babies are never disciplined: their selfish demands are always met; they are constantly fondled and loved—they are not believed to possess reason.

Normally, the anthropologist continued, when the child is three years old, the next one is born, and after a period of emotional adjustment, the child accepts its more refined role of reason. Sibling rivalry continues to exist but is usually modified in the presence of adults. The latter, for their part, do not admit that animosities exist among the children and they frequently insist, though gently, that the older children should give way to the younger ones who, they believe, do not yet have reason. Parents, for their part, love their children intensely, though when they’re above three years old the adults don’t demonstrate it as much. Sometimes they feel they love their children too much.

The story last week on “All Things Considered” adds another perspective to the Inuit approaches to developing anger control among their children. The story was reported by science reporter Michaeleen Doucleff and focused on a luncheon at an elder care center in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut. Much of the conversation with the old people, who are speaking Inuktitut, is interpreted by Lisa Ipeelie.

Over a lunch of ringed seal, beluga whale, and frozen char, Martha Tikivik, 83, tells Doucleff that the Inuit traditionally did not have the time for anger in their lives. “It just got in their way,” the lady says. She adds that displays of anger didn’t solve problems—they simply hindered other productive activities.

The reporter mentions that anthropologists—she does not say who—have discussed the calmness that characterizes everyday life among the Inuit. She adds that elders with whom she has discussed the issue blame the “colonization” over the past hundred years that has destroyed the Inuit traditions. So their communities are working to retain their ways by focusing on their styles of child raising.

Doucleff meets a lady named Goota Jaw, who teaches a class in a local college on traditional Inuit parenting. Ms. Jaw cuts to the chase by pointing out that Inuit and European Canadian approaches to parenting are very different. Her husband, who is a Caucasian, will discipline their young child by shouting things like “go to your room.” She strongly disagrees with such displays of anger. She disciplines the child by telling stories, not by yelling.

The stories told to children are handed down over the generations and designed to mold their behavior into approved patterns. For instance, Jaw tells the reporter that they have stories that they hope will keep their children safe from drowning in the ocean, an ever-present danger for people who live along the coasts. Instead of yelling at their kids to stay away from the water, parents will tell them the story of the sea monster who will put you in a big pouch and drag you down into the ocean.

Myna Ishulutak joins the conversation and relates a story that is told to children who need to learn to wear their hats in the bitter cold winter weather. According to that story, when you go out without a hat, the northern lights will grab your head and play soccer with it. She laughs and says that when she was a kid, she was scared of losing her head if she forgot her hat.

Ms. Doucleff concludes that the point is not to scare the children needlessly. In fact, the severity of the story—its scariness—should be modified to meet the needs of each child. She introduced scary monsters into her own home, she says, with similar goals as the Inuit. She wanted to make sure her child was learning to share, the goal of the sharing monster. And to urge her 3-year-old daughter, Rosy to get on her shoes, the child has to confront the shoe monster.

So the reporter asks Rosy, who is in the lunchroom with her mother, what the shoe monster would do with kids who resist putting on their shoes. “He comes and takes them down in the hole right there,” the kid replies. The reporter asks her daughter which form of discipline she would prefer, yelling or stories. Stories, the child answers.

Doucleff concludes her report with a statement by a psychologist from Villanova, Deena Weisberg, who says that stories are widely used in many societies to communicate ideas because we learn best through narratives. Stories are the best way to diminish anger, eliminate shouting, and best of all, turn discipline into fun. The Inuit, as well as several of the other peaceful societies, are aware of the value of inflicting scary monsters on their children as discipline for them while avoiding displays of anger as much as possible.