I recently became aware of the fact that someone I deeply respect, who friended me on Facebook a couple years ago, has unfriended me. I have no idea why. Perhaps I said something offensive in one of these news posts—I’m clueless. But in the spirit of the holiday season, I’m stepping back from my lingering angst about it. There is something intriguing, and peaceful, about breaking off relations in such a non-confrontational way.

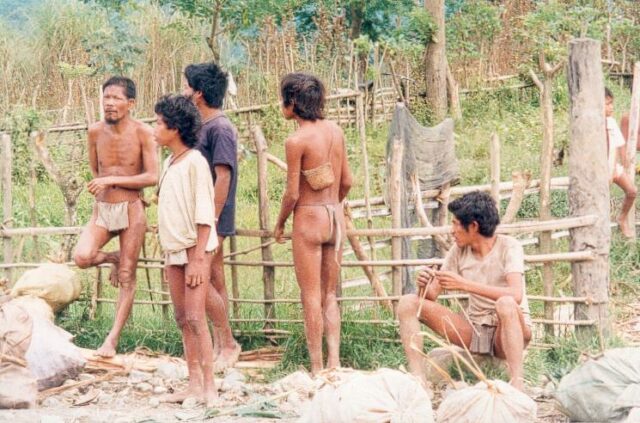

The stresses and uncertainties about our (former?) friendship led me back to the peaceful societies literature. How do they confront the messiness of human social interactions? Other than simply summarizing that they handle their relationships nonviolently, it may be best to look for specific societies that have, or had, Facebook-like relationships. The Buid are one of the best examples of that.

The Buid appear to make at least some use of the social media. A Google search in 2018 for Pamana Ka, the name of their high school in Danlog described again in a news story on September 4 this year, turned up several references to Facebook posts in which the school system is featured. Which makes one wonder how much the Buid with smartphones and access to the internet use the social media. For there are some surprising similarities between Facebook and the Buid style of peacefully communicating.

For a moment, we need to reflect on the way the Buid normally socialize—by making comments to a group of people, usually sitting back to back or all facing a distant mountain peak (Gibson 1986, p.46). Everyone addresses the group as a whole, rarely if ever speaking directly to another person. It is as if the Buid were anticipating Facebook many decades ago. While a Facebook member can, of course, send comments to specific individuals, many Facebook members direct their comments to their entire group of “friends,” hundreds or perhaps even thousands of people.

Much of the news shared on Facebook is less than earthshaking: “I took my dog for a walk this morning,” or some such. Though some people will care, many will read it, grunt, and go on to the next post in their news feeds. Or put up their own news about the performance of their kid in the school play last night. Or how cute the cat is. The things that matter to people.

The Buid in their traditional villages similarly make comments to groups of people without worrying about who will or will not respond. Much of the personal news and opinion is banal, in Facebook and in the Buid village, but that’s the charm, or at least the potential charm, of both. A Buid man might make a comment about his kids one morning to a group of his friends, who would similarly grunt, respond or not as they felt so inclined, and perhaps make a comment of their own.

The similarity is startling. Instead of directing comments at specific individuals and setting up potential conflicts, the Buid as well as many Facebook members just make their comments to an undifferentiated group. People will respond when and if they feel like it. They may break off their friendships with others without a word of confrontation. Anthropologist Thomas Gibson does not indicate if the Buid have different gradations of grunts people might make that would provide a pre-internet equivalent of “like.” But he does make it clear that the reticence of the Buid toward others—their attempts to never put anyone else on the spot—are an important element in their culture of peacefulness.

The big question therefore is whether the similarity with the social media, of sending comments to an undifferentiated group of friends without them having any obligation to respond, could become a foundational element in building a more peaceful world. Obviously many other elements will need to be developed before cultures of peace will take off more widely, but communicating with an indirect, nonthreatening, undemanding manner, as the Buid are so expert in doing and as Facebook seems to reinforce, may well represent one of the beginning elements of a coming culture of peacefulness. It won’t replace direct communication right off, but it may help us to feel our way forward. In a non-confrontational fashion.

Perhaps my former Facebook friend will seek to reestablish our friendship, or perhaps not. However it turns out, it will continue to be handled in a non-confrontational fashion. The Buid would approve.