A faith healer who has gained a significant following in East Africa over the past 20 years won an important court victory last week in Sumbawanga, the major city of the Rukwa Region of Tanzania. Roman Catholic evangelization in the Rukwa Region and the surrounding areas of southwestern Tanzania have had a major impact on the Fipa people of the area for over a hundred years, according to a book by Smyth published four years ago.

Although the church is a significant force in Fipa society, Smythe argues that the people are well known for retaining some of their traditional beliefs as well. It is not surprising that the diocese in Sumbawanga has been leading the fight against a cult and its leader that the church has officially banned and excommunicated.

The story goes back to a young priest named Felician Venant Nkwera, who came from the Iringa Region of southwestern Tanzania, near Lake Malawi, south of the traditional Fipa territory. Born in 1936, he entered the priesthood in 1968 in a southern town, but was soon assigned to Madunda Parish, in northern Tanzania. He baptized a sick infant, who had almost been pronounced dead, and when he poured water on the infant, the child miraculously seemed to be restored to full health.

The story goes back to a young priest named Felician Venant Nkwera, who came from the Iringa Region of southwestern Tanzania, near Lake Malawi, south of the traditional Fipa territory. Born in 1936, he entered the priesthood in 1968 in a southern town, but was soon assigned to Madunda Parish, in northern Tanzania. He baptized a sick infant, who had almost been pronounced dead, and when he poured water on the infant, the child miraculously seemed to be restored to full health.

The young priest reported the incident to his superior, but it was passed off as a minor work of God. The healing continued through his hands. In May 1969, Fr. Nkwera started openly praying for spiritual healing and performing acts of exorcism. His reputation quickly spread, and he opened what he calls the Marian Faith Healing Centre, which is attended by people known as “Wanamaombi,” or people who pray. Fr. Nkwera credits the healing to his visions of Mother Mary.

An unnamed individual from Uganda (unnamed because the group has been banned, so anyone who participated in their rituals would risk being excommunicated) attended one of the services and described the proceedings. “This celebration, like any other ‘liturgical’ observance, at this already marvelous centre, left an indelible memory in my mind. Co-celebrated by three priests, two hailing from Uganda, while the other was from Kenya, it was a ‘fervent mass’ whose … elaborate ‘liturgical’ particulars and willfully active participation of the congregation are still very vivid.”

The story, oddly enough, appeared in a Catholic Church magazine, published in Uganda in February 2009. The editors of the magazine inserted quotation marks around every phrase by the anonymous author that the church would take issue with.

The author’s description of the religious service continued, “The choir intoned Christmas and Marian hymns, some of which were common English tunes I know. But, in Kiswahili, I was left mesmerized and lost in utter awe. Everybody, child and adult alike, seemed to know the reason why he or she had gone to the centre.”

He stayed at the Marian Faith Healing Centre for two weeks, observing people attending, praying, expressing their devotion, reciting the rosary, and participating in masses. The center holds monthly vigil masses, and “water services,” during which Fr. Nkwera blesses water which is sprinkled on all who have come for healing. Nkwera argues that the water has the same purposes as the healing waters used at Lourdes, in France. The faithful come from other countries in Africa, such as Uganda, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Sudan, as well as from outside Africa.

The church hierarchy reacted in February 1990 by ordering Fr. Nkwera to immediately stop performing his functions as a priest and to return to Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanzania. They then decided to ban his activities completely, accusing him of placing Mary above God. The church also objected to contests with the Devil that occurred during his services, when people would shout out, from a trance, “we hate you”—meaning the devils around them.

The story does not end with the excommunication of the priest, however. The church, and the Wanamaombi, took their disagreement into the courts. According to church officials, the defrocked priest and his followers persisted in going into churches and shouting their devotions, disturbing and interfering with the masses. The dissidents insisted that they had the right to enter and worship as they wished, and denied that they had disturbed the worshipers.

In May 2003, the Resident Magistrate Court in Rukwa agreed with the church hierarchy, that the excommunication had been fair and proper. It directed each side of the dispute to worship in different buildings and to follow whatever procedures they wished on their separate premises. Fr. Nkwera and his group appealed the decision to the High Court of Tanzania, but that body dismissed the appeal because an overly long period of time had elapsed.

The Marian group decided to appeal that decision to the Court of Appeals, which ruled last week in its favor. The three judges on the Court of Appeals, January Msoffe, Nathalia Kimaro and Bernard Luanda, ruled that the High Court had erred in deciding that too much time had elapsed in filing the original appeal. That appeal had been legitimately delayed, it said, not due to any fault of the appellants. Fr. Nkwera and his followers were free to continue their appeals of the original Sumbawanga Court decision against them.

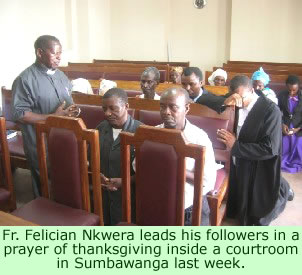

When the court deputy registrar read out the decision in the courtroom, Father Nkwera led about 20 followers in an immediate, impromptu prayer session right then and there. A photographer captured the moment. It is not clear from the news stories on the controversy how many Fipa themselves are actively involved in the breakaway group, or whether the church diocese in Sumbawanga just happens to be the focus of church opposition to the movement. Along with recent stories about witchcraft practices and traditional healing among the Fipa, this saga about spiritual healing provides another glimpse into their current religious beliefs.