Societies that want to hold on to their peaceful traditions have to be concerned about whether the education of their children will change their cultures, their economies, and their social values. Adults as well as young people face the challenge that education poses for a society—the potential advantages to individuals of more comfortable lives, versus the possible disconnect from the home village and its values.

The Amish deal with the violent social practices that surround their society by educating their children themselves. The Hutterites establish their own schools on their colony grounds, along with outside, public schools, to make sure their traditions are imparted early to their children.

The Orang Asli societies—the Semai, Chewong, and Batek, among others—agonize about the role of education for the future of their children and their communities. Colin Nicholas, from the Centre for Orang Asli Concerns, argued in 2008, during a public discussion in Malaysia about the education of indigenous minority peoples, that the most important concern for those societies is retaining their cultural identity in the context of the educational system.

The peaceful societies of India, and of course their young people in particular, face these issues as well. Last week, one of India’s major papers featured the fact that a Birhor boy had just abandoned his fully-funded education and returned to his native village, to a life of poverty and menial labor, as the journalist characterized it. The press focused on the decision of that one boy to return to his village because the school is run by India’s largest steel plant, Bokaro Steel Limited (BSL).

The Telegraph of Calcutta reported that Binod Birhor had chosen to return to his home village in Gomia Block, Jharkhand State, rather than stay and complete his studies. The paper estimated he would soon become a day laborer, earning Rs 100 (US $2.20) per day. Another student, Sawan Birhor, expressed his disdain for his former classmate. He said he would stay and complete his education, so he can earn Rs 15,000 (US$330) per month. “Binod would remain a labourer,” he evidently told the reporter scornfully.

The Times of India carried a similar story, though without the quotes from the classmate. That paper wrote that Binod had gone home for his summer vacation in May and had decided to not return. Neither paper gave Binod’s reasons for abandoning his education. Perhaps the environment among the Birhor boys had gotten to him, or the values they seemed to share in the dormitory. It is hard to know, though the background of the issue provides clues.

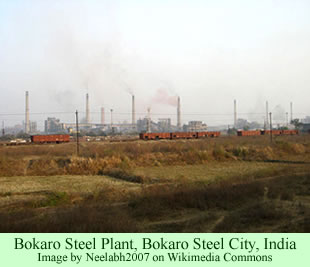

Bokaro Steel Limited is owned by a state corporation, the Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL). Located at Bokaro Steel City, in Jharkhand state, it is considered the largest steel plant in the country. Social responsibility initiatives taken by the corporation have included the establishment of medical care facilities, roads, sanitation plants, cultural activities, safe drinking water, and, in 2001, a fairly high profile school for 15 Birhor boys.

Bokaro Steel Limited is owned by a state corporation, the Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL). Located at Bokaro Steel City, in Jharkhand state, it is considered the largest steel plant in the country. Social responsibility initiatives taken by the corporation have included the establishment of medical care facilities, roads, sanitation plants, cultural activities, safe drinking water, and, in 2001, a fairly high profile school for 15 Birhor boys.

The Times of India ran a feature story on the special Bokaro Steel school in April this year. By then, four of the original boys had dropped out of the program, but 11 remained. The feature focused on five of the older boys, including Sawan, the critic of the dropout, who had just completed their class X exams. Those five had chosen to not return to their home villages at the end of the school year, in March, for their summer vacations. BSL officials asked them why.

They replied that they had no interest in going home: they would miss the televised Indian Premier League ( IPL) professional cricket matches. They also loved to watch movies starring Katrina Kaif, a popular young Indian film star. They made it clear that they had completely lost interest in the lives of their relatives and friends in their villages, Tulbul and Khakhanda, located only 70 km away.

One of the young men, Santosh, from Tulbul, explained to the Times his reason for staying in the dormitory. “I found it better to live here under the fan and watch my favourite TV programmes than go home. I don’t [get] good food like the hostel in my home. My parents are poor and can hardly arrange two square meals[a day]. Last year, when I went for the vacation, I [spent] most of the time alone under [a] tree reading books.”

The other boys expressed a similar sense of disconnect from their homes. Sawan Birhor told the paper, “now, people look at us differently in the village. My old friends go to work in the morning and there is no one with whom I can spend time at my village. There is no TV in our village. I miss movies, particularly Katrina Kaif movies.”

Tobolal Birhor had his own reasons for not wanting to go home for the vacation: “Here, we play games like football. There is no such arrangement in our village. I dropped the idea of going to [my] village after [the] examination because of the heat. It is pathetic to live in huts in this hot weather.”

The paper mentioned that, at first, the boys had a rough time adjusting to life away from their villages, and they frequently fled back home from the dormitory. They missed their families and their forests. But they soon became comfortable with urban life, deciding that it was in fact better than their villages.

Many other traditional societies face similar issues. The Buid are getting schools in their own villages, which allow them to preserve, to some extent, their own local cultures. The village schools also allow the young people to make informed choices as to how much of the culture to continue and what to do with their futures. It’s clear from the recent press reports that some young Birhor males enjoy watching a lovely movie actress in comfort much more than participating in the lives of their communities.