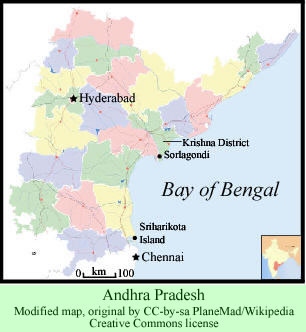

The government of India, a research foundation, and a volunteer organization have teamed up to help an impoverished Yanadi community begin an eco-friendly, low-input crab farming operation. According to a news report in The Hindu on Friday, the new project, fostered by the cooperating agencies, is located in the village of Sorlagondi, near Nagayalanka, in Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh, southern India. The village is 200 miles north of the city of Chennai, near the coast of the Bay of Bengal.

R. Ramasubramanian, Senior Scientist for the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation based in Chennai (formerly Madras), described the crab farming operation for the press. Since the crab farm is located on a tidal river, no pumping of water is necessary—the reversing tidal flows provide the necessary exchanges of water. Mangroves planted along the banks give shelter for the animals and supply nutrients, so there is no need for any food input. Evidently, a similar technique is being used at a research site in Tamil Nadu to the south and in some Southeast Asian locations.

R. Ramasubramanian, Senior Scientist for the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation based in Chennai (formerly Madras), described the crab farming operation for the press. Since the crab farm is located on a tidal river, no pumping of water is necessary—the reversing tidal flows provide the necessary exchanges of water. Mangroves planted along the banks give shelter for the animals and supply nutrients, so there is no need for any food input. Evidently, a similar technique is being used at a research site in Tamil Nadu to the south and in some Southeast Asian locations.

A. Balaram, Assistant Director for inland fisheries in the Indian government’s Department of Fisheries, told The Hindu that the Yanadi in the village have harvested crabs worth Rs. 35,000 (U.S. $768) from their two-acre facility. G. Rathinaraj, Deputy Director of the Marine Products Export Development Authority, another Indian Government agency, said at a media event on Wednesday last week that there was, potentially, a large market potential for the crabs.

The president of Praja Pragathi Seva Sangham, a volunteer organization that has been involved, said that the initiative will help the Yanadi fishermen earn more income. They have been suffering due to declines in their fish catches. The new approach to fish farming should allow them to raise both small fish and crabs in the same ponds. Mr. Balaram emphasized the eco-friendly nature of the project. He hoped that the approach could be encouraged elsewhere.

The cooperation and involvement by the different government agencies provides a striking contrast to the way the Yanadi were recently treated in another district of Andhra Pradesh, as reported last July. The treatment in Krishna District also contrasts with 40 years ago when the Indian Space Research Organization decided to turn the marshy, coastal Sriharikota Island, located on the Bay of Bengal nearer Chennai, into the national space launch center. The Yanadi residents of the island were unceremoniously removed from their huts and moved off the island.

According to Agrawal, Reddy and Rao (1984), the Yanadi exiles from Sriharikota had numerous problems afterwards. As of the date of that article, they were required to live in a couple permanent villages, which caused problems. They no longer had the freedom to manage the space around their huts as they had before or to construct separate huts for their older children. They were restricted from utilizing the spaces in front of their huts for their living activities, and they were restricted from enjoying the individualism that their hut-placement previously had fostered.

Confined to specific localities in the resettlement villages, they no longer had the ability to gather at will in their neighborhoods. Furthermore, local resources were over-utilized, and the concentration of people produced a lot of pollution. Human relations in the resettlement villages were also affected, as people lost their individual privacy and independence.

Rao subsequently published (2002), a book-length ethnography of the Yanadi which provides a more up to date analysis of the changes to the society and economy suffered by the Sriharikota Yanadi people when they were resettled. The recent, multi-agency, fish pond project farther to the north is a hopeful sign of official interest in the society, at least the people of Sorlagondi.