Can an overabundance of alcohol prompt people to commit acts of violence? Can it make a society more violent? The Inuit of Nunavut seem to feel it can and they have been testifying about it recently to a territorial investigative commission.

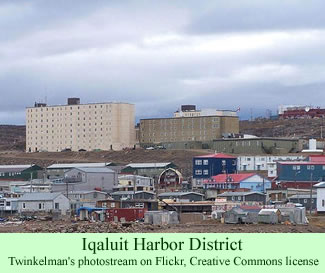

The Nunavut Liquor Act review task force heard testimony in the territorial capital of Iqaluit on Wednesday last week, the ninth community the task force has visited so far. It plans to visit every community in the territory and solicit input on possible ways to address the problems that rampant consumption of alcohol pose in Arctic Canada.

The Nunavut Liquor Act review task force heard testimony in the territorial capital of Iqaluit on Wednesday last week, the ninth community the task force has visited so far. It plans to visit every community in the territory and solicit input on possible ways to address the problems that rampant consumption of alcohol pose in Arctic Canada.

The first speaker at the Iqaluit hearing was Mr. Joanasie Akumalik, a city councilor, who spoke of his experience 20 years earlier. He had been drinking hard one night, he said, and woke up in the morning to find his wife gone. He recalled vaguely beating her during his drinking. He searched the house, even looked in the large garbage storage bin—he was afraid he had killed her in his drunken rage.

What had happened is that he had broken her jaw, and she had been medevaced to Montreal for emergency treatment. He subsequently was given the option of serving time in jail for his assault, or undergoing a rehab program in Toronto. He chose the latter, and has been sober ever since. He made the point to the commission that he was only able to take advantage of the program because his employer was willing to allow him the time off from work. He asked the commission to urge employers in Nunavut to keep employees on their payrolls when they need alcohol rehabilitation.

Numerous speakers pointed out that alcohol is a foreign substance in Inuit culture, which explains why overdrinking fosters violence, suicides, child abuse, and poverty. Donna Adams, the President of Qulliit Nunavut Status of Women and chair of the task force, commented that “alcohol is everywhere” in the territory.

Many of the speakers made positive recommendations for the commission to consider. People suggested the need for treatment centers and rehab facilities right in Nunavut, so alcoholics could be helped nearer their homes and not have to go south to the big Canadian cities.

Being able to go out on the land while undergoing rehabilitation could be a positive aspect of the treatment, one man argued. “There’s a lot of people hurting…a lot of people who want help,” he stated. He believes that treatment centers right in Nunavut would help reduce the crimes caused by drunk people.

Another man wondered if Nunavut should emulate Greenland, which rations alcohol by community. He asked if the operation of territorial liquor stores would help control the sale. Another speaker responded, however, that when a liquor store opened in Iqaluit in the 1960s, there was an epidemic of homicides, drunkenness, and people freezing to death on the streets. She suggested that the bars should be required to monitor the behavior of their customers more closely.

One woman advocated abolishing the availability of hard liquor and allowing only the sale of beer and wine. She blamed the easy availability of vodka for many of the problems. But another said that cracking down too hard on the bars would spur the growth of the bootleggers’ businesses. Some speakers emphasized the importance of educating young people about the dangers of alcoholism.

The mayor of Iqaluit, Madeleine Redfern, advocated changing the laws to reduce the amount of liquor residents can purchase at any one time. Other speakers, blaming the problem on the bootleggers, had specific fixes for the problems they feel that those individuals cause. The Liquor Act Review task force will continue to meet in Nunavut communities through May, and take written testimony through the summer. Donna Adams, task force chair, indicated that people in all the Nunavut communities are saying similar things.

One speaker in Iqaluit expressed cynicism that the territorial legislature will do anything helpful, even after it receives a report from the task force. Isaac Sobol, the chief medical officer of the territory and a member of the task force, took exception to that possibility. “The government needs to think about its entire approach when it comes to alcohol,” he replied. “If [the members of the legislative assembly] are not doing that, get rid of them and get some people who will.”

News stories about the commission hearing did not mention that agencies already exist, such as Drug Rehab Nunavut, to help alcoholics get the treatments they need.