To judge by the news last week from a village near Sumbawanga, in southwestern Tanzania, the practice of traditional healing continues to be an important aspect of the peaceful Fipa culture.

Recent news from the Rukwa Region of Tanzania has covered other stories about traditional healers. Last year, a predatory healer attacked his victims with his “medicine” and nearly killed them after successfully robbing them. A few years ago, a healer told his followers in his village that he was going to visit the gates of hell. He jumped into a river and drowned.

Recent news from the Rukwa Region of Tanzania has covered other stories about traditional healers. Last year, a predatory healer attacked his victims with his “medicine” and nearly killed them after successfully robbing them. A few years ago, a healer told his followers in his village that he was going to visit the gates of hell. He jumped into a river and drowned.

The news last week may not have been so dramatic, but it threw a little more light on the traditional healing profession among the Fipa. Ms. Christina Chenga, an 18 year old woman in the village of Mtimbwa, declared she had been having strange dreams that directed her to start healing people. She is the only daughter of Mrs. Leonira Fundimabao, a peasant woman.

Ms. Chenga told a newspaper reporter that she dropped out of the local secondary school when her dreams directed her to. Mrs. Fundimabao told the press that her daughter administers a cup of herbal preparation to each of the patients who come to their home. She said they get up to 2,000 patients daily.

The District Commissioner, Colonel John Mzurikwao, admitted he was aware of the curing going on in the village. He said he had directed the District Medical Officer to visit the village, along with other officials, to investigate the safety of the herbs being used.

Ms. Chenga said that her cup of herbal medicine, for which she charges 500 Tanzanian Shillings (US$0.33), cures cancer, HIV/AIDS, and other illnesses. She says that she has gotten calls back from satisfied patients who told her they were feeling better.

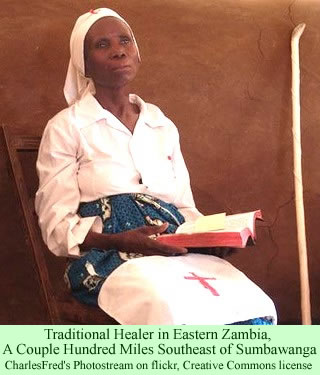

This brief news story provides several clues about changes in Fipa attitudes toward their traditional healers since 1964 when Willis finished his studies of magic and medicine in Ufipa. He noted that all of the traditional healers were men—it was an exclusively male profession. The Fipa healers who made the news in 2007 and in 2010 were also both men. The news story last week indicates that the new healer is getting business, so it would appear as if the formerly all-male profession has changed. Women act as healers in other nearby societies, as the photo above illustrates.

Willis observed that patients went to their village healers for treatments of physical ailments and mental illnesses, and for assistance in obtaining desirable objectives. He describes in detail the different ingredients that the traditional healer might use in his medicines—bits of animals, vegetables, and minerals found in the bush. A woman suffering from dizziness, for instance, might have been treated by a healer with pieces of swallow’s nests, symbols of self-contained, but fixed, stability.

The healers in the 1960s might also use, in their preparations, hair from the neck of a male goat, pieces of muskrat, parts of a net used to trap otters, bits of an elephant’s ear, or some of the mounds made by moles. Each ingredient had symbolic values to the Fipa of the period. The news story last week was unfortunately brief, but it did not appear as if the young woman is using anything more than herbal preparations, though the reporter may have missed part of Ms. Chenga’s story.

Willis reported that sometimes healers administered their preparations by burning them into ashes and rubbing them into cuts on the skin of the patients—as the bogus healer did to his victims in 2010. He also reports that healers at times administered their potions to their patients orally, as the young woman near Sumbawanga does today.

He indicated that the tradition of healing had changed a lot in Ufipa by 1964 when he completed most of his field work. An earlier, elaborate structure of mystical beliefs and behaviors had collapsed with the introduction of Roman Catholicism in the late 19th century. The moral and social forces involved with traditional healing were disintegrating. The healer, the asinaanga, in Fipa society evolved from a magician-doctor who practiced divination, to a shaman who was able to divine through spirit possession, to, in 1964, an individual who dispensed simple, ad hoc, medicines.

The news story last week indicates that the last stage of healing that Willis observed is still active in Ufipa. If the numbers of patients Ms. Chenga receives are to be believed, it confirms that the belief in healing is still strong among the Fipa people.