The earthquake that devastated the Dzongu Lepcha Reserve in Sikkim on September 18th continues to produce its aftershocks—both in the local mountains and in the attitudes of the Lepcha people.

A news story last week in The Hindu, a major daily in India, reported that another minor aftershock had just hit the same region. The low-intensity tremor, 3.2 on the Richter Scale, killed two people. One man, 27 year old Sonam Wangyal, from the village of Lingdem, just south of Mangan, died when he fell off the Lingdem Bridge. The other was an 85 year old man who died of a heart attack as he rushed down the stairs of his home in the village of Nung, inside the Dzongu Reserve. The newspaper did not give the name or any further information about the old man.

A news story last week in The Hindu, a major daily in India, reported that another minor aftershock had just hit the same region. The low-intensity tremor, 3.2 on the Richter Scale, killed two people. One man, 27 year old Sonam Wangyal, from the village of Lingdem, just south of Mangan, died when he fell off the Lingdem Bridge. The other was an 85 year old man who died of a heart attack as he rushed down the stairs of his home in the village of Nung, inside the Dzongu Reserve. The newspaper did not give the name or any further information about the old man.

A few days later, the Deccan Herald, another Indian paper, reported that the Lepcha residents of Chungtang, whose homes were devastated by the big September earthquake, are now demanding more compensation from the company that is building a nearby Teesta River hydropower dam. The people blame the earthquake on the Teesta Uria company, because it is blasting tunnels in the mountains as part of the project.

A memorandum from the 170 families in the town cited an earlier report from the Mines and Geology Department, which had warned of potential damages to homes in the area from any blasting. The earlier report, according to the memorandum, “proved beyond any doubt that the fear and apprehension of the people regarding the negative impact of the project were correct.” The memo mentioned that 20 people had already died in the area before the earthquake had even occurred.

The memorandum stressed that the people of the Chungtang area need to have their houses rebuilt by the company. It also demanded that the company should rebuild the infrastructure that the earthquake destroyed.

Part of the tragedy of the past week was described in detail by a couple news sources published in Sikkim itself. Evidently, the 85 year old man who had had a heart attack during the latest tremor and died in Nung was actually Samdup Taso, the Kanchenjunga Bongthing. He was the senior priest of the Mun faith, which is the traditional religion of the Lepcha people.

The Sikkim Times confirmed that he had died of shock during the aftershock. It reported that Samdup Taso was the last of the Kanchenjunga bongthings, the priests who performed the central rites of their faith that venerate their sacred mountain. It is not only the world’s third tallest peak, but it is also the god from which the Lepcha descended. The rites of the Kanchenjunga Bongthing used to be the central, unifying, cultural force for the people.

Dawa Lepcha, a resident of Dzongu, said that since Samdup’s son has not followed in his father’s footsteps, and the old man had not performed his rites for decades, the critical Mun rituals have now passed into history. “It is a huge loss for the Lepcha community, especially for those who knew him and his importance,” Dawa said.

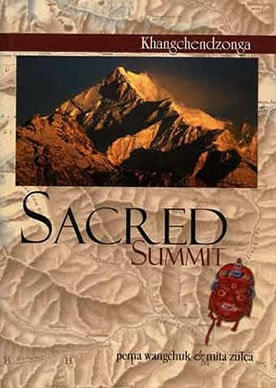

The news reporter refers to a book written by Pema Wangchuk and Mita Zulca called Khangchendzonga: Sacred Summit (Gangtok: Pema Wangchuk, 2007). The work indicates that the performance of the rituals would soon be lost since Samdup Teso had discontinued performing them in the mid 1970’s. In fact, the rituals were preserved, recorded, by the Danish scholar Halfdan Siiger, who had gained the confidence of Sandup’s father, the previous Kanchenjunga Bongthing, in 1956. The elder priest had allowed him to record the rituals.

The news reporter refers to a book written by Pema Wangchuk and Mita Zulca called Khangchendzonga: Sacred Summit (Gangtok: Pema Wangchuk, 2007). The work indicates that the performance of the rituals would soon be lost since Samdup Teso had discontinued performing them in the mid 1970’s. In fact, the rituals were preserved, recorded, by the Danish scholar Halfdan Siiger, who had gained the confidence of Sandup’s father, the previous Kanchenjunga Bongthing, in 1956. The elder priest had allowed him to record the rituals.

A longer article appeared in another news source, Sikkim Now, on Tuesday last week. The bulk of that piece consists of lengthy extracts from the 2007 book by Wangchuk and Zulca. It appears as if Nung is one of six small villages in the Tingvong cluster of communities, on the north side of the Talung, the major river that forms the heart of the Dzongu.

The authors maintain that the Lepcha people used to be nomadic hunter gatherers and shifting agriculturalists before they settled into permanent agriculture. Their first permanent settlement in Sikkim was in the hills north of the Talung, and specifically the Nung area, because it has the best possible view of the sacred mountain, Kanchenjunga, without intervening hills to block the view. It was only reasonable for the Lepcha to institute the worship of their god at this place.

The rituals that Samdup used to perform at Nung were the basis for Lepcha nationalistic pride. Other bongthings also offer rituals to Kanchenjunga, but the one at Nung was the most important. The secret ritual, and its accompanying processional song, would now be lost except for the recording that Siiger made and transcribed into his book The Lepchas: Culture and Religion of a Himalayan People (Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark, 1967).

The gradual influx of Buddhism into Sikkim began to dilute the Mun nature worship several hundred years ago. The annual Kanchenjunga rites at Nung were the strongest surviving relics from the earlier era. The Bongthing from Nung used to process to the seat of Sikkim power, the capital at Gangtok, where the Chogyal, the Buddhist King, would honor him with many gifts and a symbolic yak, obtained from much higher mountains. The Bongthing would take it all back to the altar at Nung with great ceremony.

An elephant tusk, a gift of an earlier Chogyal to an earlier Bongthing, had stood next to the altar at Nung, but in recent years it has disappeared. In Wangcheck and Zulca’s 2007 account, the Bongthing lived in a dilapidated cottage, the altar had obviously not been used in decades, and the special elephant tusk, which Siiger had noted in the 1950s, had disappeared.

Wangcheck and Zulca recount various local stories about the dissolution of the once-proud ceremonies and the priestly family that had performed them. Alcohol, theft, family troubles—all were symptoms of a faith that was no longer seen as relevant. The dissolution of the Sikkim monarchy and the way the state joined the Indian union in 1975 contributed to the increasing sense of irrelevance, so the Bongthing abandoned performing the sacred rites of Kanchenjunga. The Wangcheck and Zulca account of this dying faith in the Sikkim Now blog post is a fitting tribute to the old man. He died during a mild earthquake last week, but at least 36 years before he had been helpless to stem the desertion of believers from his rituals.