On Tuesday last week, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that scientists had found incontrovertible proof about the fate of the lost Franklin Expedition. Archaeologists had found, and gotten images of, the underwater remains of one of Franklin’s ships. The intriguing aspect of the news story is that it proves beyond a reasonable doubt the accuracy of Inuit oral histories, which had preserved the memory of the rough locations of the ships for nearly 170 years.

In 1845, Sir John Franklin sailed from England in search of the fabled Northwest Passage in two ships, the Terror and the Erebus, with 24 officers and 110 crew members. The two ships sailed to West Greenland, sent back six men, and with a slightly reduced crew continued west into unknown Canadian Arctic waters. They disappeared from the view of Europeans. After three years of no word, the English, and others, became intrigued about the fate of the men. Myriads of expeditions were mounted over the next 30 years in search of them.

In 1845, Sir John Franklin sailed from England in search of the fabled Northwest Passage in two ships, the Terror and the Erebus, with 24 officers and 110 crew members. The two ships sailed to West Greenland, sent back six men, and with a slightly reduced crew continued west into unknown Canadian Arctic waters. They disappeared from the view of Europeans. After three years of no word, the English, and others, became intrigued about the fate of the men. Myriads of expeditions were mounted over the next 30 years in search of them.

The Inuit had observed the wreckage of the ships frozen into the ice, and they would tell anyone who asked. But that didn’t stop the subsequent searches. Not only are library shelves filled with volumes by and about the expeditions searching for Franklin and his men, but many scholarly and popular versions of the history have been produced, not to mention novels, poetry, songs, paintings, and television documentaries about the story.

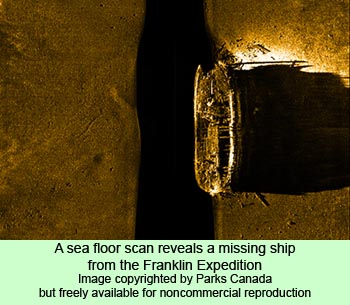

After a century-and-two-thirds, the drama was resurrected last week by the latest scientific discovery, prompting the Prime Minister himself to make a dramatic announcement: “This is a great historic event,” he said. The underwater archaeologist for Parks Canada, Ryan Harris, who managed the investigation this year, said that the wreck they had found, using advanced sonar technology, was “indisputably” one of the two Franklin Expedition ships. The sonar images of the underwater remains show that the main deck of the ship is still mostly intact, supporting hopes that additional remains of the expedition will be found inside it.

In addition to finding, finally, dramatic proof of what had happened, numerous observers noted the fact that nearly 170 years ago some Inuit people had seen the wrecks, observed the English sailors, and told and retold their stories of the apparent fate of the expedition. The dramatic announcement on Tuesday made it clear that Inuit oral history is remarkably accurate.

Louie Kamookak, an Inuit historian from Gjoa Haven, the community that is closest to the site of the discovered shipwreck near King William Island, has studied the fate of the Lost Franklin Expedition for 30 years, with a particular focus on the Inuit oral memoires of what had happened. The current news, he said, is “proving the Inuit oral history is very strong.”

Inuit oral tradition has preserved the memory of the two ships appearing on the northwest side of King William Island, he relates. One got crushed by the ice, while the other ship drifted southward. It floated for two more years before it finally sank too. Inuit elders told Kamookak that Europeans may have been living on the ship during the first winter, but there were no signs of human life during the second.

“For us Inuit [the news] means that oral history is very strong in knowledge, not only for searching for Franklin’s ships but also for environment and other issues,” Kamookak said. He told the Toronto Star, “We can celebrate that in our time we have found one of the ships based on Inuit theories—I’m very grateful for that.”

Dr. Doug Stenton, an archaeologist and director of heritage for the Government of Nunavut, said more or less the same thing. He indicated that the archaeological team might not have made the discovery without the oral memory of the Inuit stretching back to the time of the disaster. “It’s very satisfying to see that testimony of Inuit who shared their knowledge of what happened to the wreck has been validated quite clearly,” he said.

David Woodman, the author of a book about the Franklin Expedition, had similar praise for Inuit memory. “The Inuit are validated more than anything else,” he said. “All that really happened was it took 200 years for our technology to get good enough to tell us that Inuit were telling us the truth.”

Kamookak and Woodman admitted that there were problems with the Inuit historical memories of the fate of the expedition. Their stories have eroded over time; there have been mistranslations on the part of Europeans who have interviewed Inuit elders; understandings of units of distance have varied; and different witnesses pointed to different islands as the ones near which one of the ships supposedly lay.

Woodman said he is especially eager to learn the exact location of the newly discovered ship—a spot which Parks Canada has not yet revealed. He hopes to “reverse engineer what the Inuit actually meant, as opposed to what we were told they said.” In essence, this latest story will add substantially to our understanding of Inuit cultural knowledge, a subject at the basis of a different news story three months ago about a dramatic new mapping project of Inuit trails across the Arctic landscape.