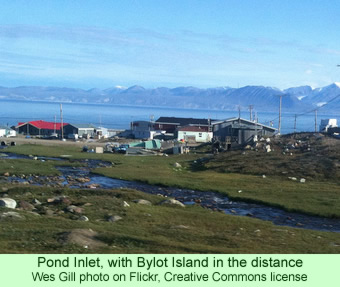

Pond Inlet has a spectacular setting. An Inuit community located along the northern edge of the enormous Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic, the residents of Pond look out across Eclipse Sound at the mountains and glaciers of Bylot Island to the north. It is one of farthest north human settlements on earth.

A reporter for the British newspaper The Telegraph, Martin Fletcher, visited Pond Inlet recently to investigate the Inuit people—their culture, history, social problems, and possible solutions to their difficulties. After describing in detail how bleak, yet beautiful, the landscape appeared to be, he discusses the friendliness and welcoming spirit of the people. The children ran up to greet him—they were eager to get the stranger involved in their fun.

A reporter for the British newspaper The Telegraph, Martin Fletcher, visited Pond Inlet recently to investigate the Inuit people—their culture, history, social problems, and possible solutions to their difficulties. After describing in detail how bleak, yet beautiful, the landscape appeared to be, he discusses the friendliness and welcoming spirit of the people. The children ran up to greet him—they were eager to get the stranger involved in their fun.

But he does not avoid reviewing the social problems of the town. Other than jobs in the public sector, there is virtually no employment. Few young people complete high school, and fewer still go south to attend Canadian universities. Housing is limited—extended families often crowd together in small dwellings. The abuse of drugs and alcohol help cause rampant domestic violence.

A nurse in the town, Sherry Parks, discusses the malnourishment that 15 percent of the community suffer from. “When people say they don’t have food in their house they literally don’t have any,” she says. The people of Pond, about 1,500, have little access to their traditional diet of fish and meat, so most of them live on junk foods. Diabetes and obesity are serious concerns.

The author encounters instances of a dysfunctional society everywhere he goes. He talks with a 17-year old boy who says he dropped out of school—it bored him—so he tells Mr. Fletcher that he sniffs propane. He encounters a Mountie with two handcuffed prisoners, convicted of committing assaults while high on drugs or drunk. Posters warn against the abuse of elders.

Suicides are “part of life up here,” according to Colin Saunders, the economic development officer for Pond Inlet. His sister killed herself. Fletcher speaks with others about the problem. Three teens committed suicide in just the first five months of 2014. Sheeba Simonee told the author that two of her brothers and three different nephews had killed themselves. Mr. Saunders says that he could point to 20 different graves in the town cemetery of people who had committed suicide.

The reporter considers the causes of these social issues. Some are obvious: the isolation of the town, the pressures of living in a small place with few opportunities and little hope of escape, the three months of polar darkness in the winter. But he passes over these minor concerns and focuses on what he argues is the major issue—the destruction of the Inuit way of life. Nothing has really replaced it.

Ms. Parks explained that in the past, when the people lived out on the land, everyone knew what was expected of them—they understood their importance to their families. “Now they’re conflicted about where they fit into this world,” she says. Mr. Saunders agrees. “We have one foot wearing a work boot and the other still wearing a sealskin kamik [a shoe],” he says.

The Telegraph reviews the history of white interference in the ways of the Canadian Arctic people. Whalers and explorers introduced fatal diseases that the Inuit had no immunity against. Fur traders fostered dependence on the money economy and on outside goods, but provided no security when the prices of furs collapsed. Missionaries replaced the traditional shamans; the Mounties introduced a system of justice that was alien to the Inuit.

Since World War II, the Canadian government has promoted permanent communities for the Inuit in order to end their nomadic lifestyle. The government encouraged them to settle in such places by offering welfare, health care, housing, and education. Some Inuit were forcibly relocated to new settlements. The police slaughtered about 20,000 sled dogs, supposedly for health reasons, but the Inuit believe that the real reason was to destroy their ties to the land.

Government agents took children away from their homes and sent them to residential schools farther south. The children were usually forbidden from speaking their own language, Inuktitut. Some were subject to emotional, physical, and even sexual abuses during their childhoods in these residential facilities. Some people in Pond spoke with the author about these abuses.

The Inuit see the European Union ban on the import of seal parts as evidence of the continuation of this repressive history. Charlie Inuaraq, the mayor of Pond Inlet, tells the writer that the price of a seal skin has dropped from $50 to $10 since the imposition of the EU ban in 2010. He argues that it is part of the pattern of keeping the Inuit in a position of begging.

Fletcher agrees. He refers to conditions in Pond Inlet as a “dependency culture” that helps explain the social problems in the community. A potential solution? To restore, as much as possible, the traditions of the people. Some Inuit still go out and hunt, but many others don’t know how, or don’t want to, or can’t afford to. A snowmobile, an essential vehicle for getting out into the country in the absence of sled dogs, costs $15,000 in Pond Inlet, twice as much as farther south in Canada.

The traditional Inuit culture survives in small pieces, like bone fragments in a polar bear carcass shot by a hunter. For instance, hunters who have successfully taken seals will invite other Inuit, via the local radio station, to come and have a share of the meat. Women still carry their babies in amautis, pouches designed for the purpose. Some women still make traditional seal-skin mitts and boots. The author, talking with a young woman selling home-made jewelry in a hotel lobby, enjoyed her demonstration of Inuit throat singing.

Fletcher concludes by considering the possibility that changes—perhaps improvements—will come about due to outside forces. Cruise ships might arrive—because of climate change opening up the waters—bringing tourist dollars. A giant iron mine is being developed about 100 miles away, which might cause environmental disasters as well as providing lots of jobs.

Inuaraq, an experienced Inuit hunter, concludes that the old days are past. He suggests that the Inuit of today must hunt for money as well as for animals.