The Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead in Wyomissing, a suburb of the city of Reading, Pennsylvania, hosted an Amish sing on Tuesday evening last week. The facility features the restored home of an Amish pioneer who settled near Reading nearly 250 years ago.

On Wednesday, the Reading Eagle, the daily newspaper of the metropolitan area in Berks County, carried a news story by Bruce Posten about the event. According to his report, over 100 guests and Amish singers, most of whom came from Lancaster County, took part in the cultural activities that focused on the Amish singing.

On Wednesday, the Reading Eagle, the daily newspaper of the metropolitan area in Berks County, carried a news story by Bruce Posten about the event. According to his report, over 100 guests and Amish singers, most of whom came from Lancaster County, took part in the cultural activities that focused on the Amish singing.

Calvin Kurtz, who serves as the chair of the Heritage Room Committee of the Homestead, said that the public sing was intended as a communal event rather than a performance of Amish songs. Kurtz also presented a DVD of “The Stoltzfus Story.”

The reporter described Amish singing as a “low, slow chant somewhat different from what is thought of as melodic singing.” He added that the hymn “Our Father God, Thy Name We Praise” is called the “Loblied.” It sometimes takes 15 minutes for the Amish to complete the four verses because of the slow, lengthy way they sing it. It is normally the second hymn sung at Amish worship services.

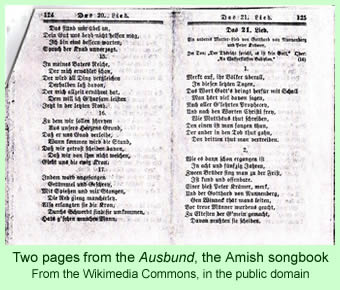

Kraybill, Nolt and Weaver-Zercher (2010) explain the importance of singing in Amish society and its place in their worship services in greater detail than the newspaper did. They write that the Ausbund, the German-language hymnal used by the Amish, has 140 hymns which were mostly written in the 16th and 17th centuries during the period of persecution of the Anabaptist people. The hymns often convey a sense of martyrdom and the need to remain firm in periods of persecution. Some of the hymns were, in fact, written by Anabaptists awaiting execution in European prisons.

But the Ausbund does more than simply recount the history of martyrdom. It also instructs the Amish about the rewards, and the demands, of worshipping Christ—and the nature of the Christian faith. The authors provide the text of a hymn in English translation and write, “these blood-soaked hymns anchor Amish people in the faith of their spiritual ancestors, women and men who heeded God’s call in the most perilous circumstances (p.25).”

Kraybill and his colleagues provide the context for the hymns in the bi-weekly Sunday morning worship services, which are hosted in the homes of different families. With about 200 people assembled by 9:00 A.M. in one of the Amish homes, a man calls out a number, rather quietly, from the middle of the group. He says it just loudly enough for others to hear, and then he starts to sing, in a slow, drawn out manner, the hymn he has chosen to begin the service.

Others pick up the hymnals scattered about the room in order to join him in the singing. They do not use any instruments, and their hymnals print just the words. Everyone knows the tunes. The song leader does not stand up or lead the singing in any other way. His spirit of yielding, hisGelassenheit, would not allow him the presumption of attempting to actively lead others.

Everyone sings, in unison, melodies that have passed down through the generations. They sing in a style that strikes outsiders as agonizingly slow. Professional musicians refer to the singing style as melismatic, but it strikes many observers as similar to the chanting of the Torah, or to Gregorian chant.

The singing captures the spirit of Gelassenheit, a concept that implies a yielding to God—and to the will of others in the church district. The singing suggests to the congregation a one-ness in God, an acceptance of His will and His timing. It reminds the congregation that they need to be resigned to the will of God and to the rules of the district. They need to let go of control and of material things, and to yield to circumstances.

The second hymn in the service, as the Reading Eagle reporter noted, is always the Loblied. It is a praise hymn, which emphasizes a request to God to bless the preachers and to incline the worshippers to receive the forthcoming message from God that the preacher chosen for the morning will deliver shortly. Singing the Loblied may take from 18 to 25 minutes, depending on the congregation, since the slow pace of the singing emphasizes the idea that everyone is yielding, rather than forcing things to go their own ways. The authors summarize that the worship service is essential for reinforcing Amish beliefs.

The singing reminds them that they are in the process of yielding to God and to one another. “The spirit of Gelassenheit brings a sense of contentment and harmony as members worship together,” the authors emphasize (p.60).

The Ausbund, the Amish hymnal, is not only essential in fostering a reiteration of Amish values during their bi-weekly church services, it also plays a central role in the occasional choice of a new minister of a district. According to Kraybill (1989), the leaders of the Amish churches, their ministers, are chosen for life by a process that combines nominations and lot.

The process works as follows. At the end of a worship service, men and women file past a deacon and each whispers the name of a nominee for minister. The names are passed along to the bishop, who is attending the service. Any man who is nominated by three or more people is included in a drawing. Usually six or seven men from the congregation will be nominated. A slip of paper bearing a Bible verse is inserted into one of six or seven hymnals, and each of the nominees is handed one of them, at random.

The man who opens his book and discovers that the verse is in his Ausbund is overwhelmed to realize that the Lord has just chosen him for the life-long, added responsibility of service to the community. The divine choice prevents any quarreling with the leadership selection process, and it reaffirms the unity, stability, authority and peacefulness of their community.