A food staple of the Yanadi a century ago—rats—has recently become a source of cash income for them, according to a report in a major Indian daily newspaper last week. Changes such as this in the cultures of small, traditional, peaceful societies can be fascinating.

Edgar Thurston, writing the standard descriptive work about the indigenous peoples of South India in 1909, observed that the Yanadi were experts at catching bandicoot rats. The Yanadi hunter first made an alternate escape hole from the animal’s burrow. Then, using a method called voodarapettuta, he stuffed a pot with grass and lit it. He placed the mouth of the pot against the entrance hole to the burrow and blew through a small slit in the pot, which forced in smoke.

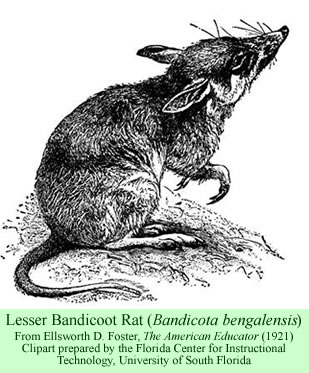

Any beekeeper who has stuffed grass or hay into a metal smoker, lit it, and used it to puff whiffs of smoke into a bee hive—to calm the insects before examining the colony—will understand the principle. When the bandicoot rat (unrelated to the marsupial bandicoots of Australia) plunged out through the second hole to escape the suffocating smoke, the hunter killed it, according to Thurston.

Any beekeeper who has stuffed grass or hay into a metal smoker, lit it, and used it to puff whiffs of smoke into a bee hive—to calm the insects before examining the colony—will understand the principle. When the bandicoot rat (unrelated to the marsupial bandicoots of Australia) plunged out through the second hole to escape the suffocating smoke, the hunter killed it, according to Thurston.

In 1962, a standard book on the Yanadi by V. Raghaviah elaborated on their reasons for eating the rats that they smoked out of their burrows. Raghaviah pointed out how fond the people were of these rats because they thought that the flesh of the animals gave them immunity to rheumatism, inhibited grey hair, and even helped keep the frames of older people erect, supple, and elastic. Eating rats helped ward off old age.

That author also described the way the Yanadi loved to rip apart the underground passages of the rat burrows to find their little grain caches. Families would have festive times doing that kind of gathering, their children enjoying peering into the labyrinthine tunnels as the adults worked to rob the rats of their stored food.

Last Tuesday’s issue of The Hindu provided a clue to the ways they have adapted to modern conditions. The article describes how the Yanadi are still skilled at smoking out rats—and the fact that they now provide an invaluable service to neighboring farmers, for a fee. The journalist may have used language that is a bit overdone to describe the “droves of farmers” who pursue the nearby Yanadi rat-catchers. The problem is that a plague of rodents has been destroying their grains.

A crop called black gram, a bean that is used to make dal—an important food in India—has mostly failed due to a shortage of water, so the depredations of the rodents have been critical. The huge Lesser Bandicoot Rats can grow to 40 cm, or 15 inches long, and can be dangerous to human babies as well as cereal crops. Controlling the numbers of rats will help preserve the black gram that remains in the fields or is held in storage facilities.

The newspaper’s description of the techniques used by contemporary Yanadi might as well have come straight out of Thurston, except that they do not provide escape holes for the animals. “They spot a burrow,” The Hindu writes, “cover it with a container having the burning dry grass inside, and generate smoke through the vessel with the help of a hand-held fumigator. And, the rodent is sure to die of suffocation…”

The Yanadi people are now heroes. It is not clear if they still eat rats, however, which would surely still provoke animosity among surrounding Hindus. It would appear from the news story as if they simply enjoy controlling the rat populations and being paid for their services. The Andhra Pradesh state government, however, announced this Tuesday that it will be establishing village grain banks for Yanadi communities, as well as some other rural people affected by the drought conditions and threatened by starvation.