In rural northern Missouri, Maudie Oliver doesn’t mind earning a lot of money each year by driving the local Amish, but that doesn’t stop her from condemning their pacifism. Along with other residents of Schuyler County, she is proud of her patriotism. “They do not honor the flag or go to the military,” she said. “We’re protecting them and all their kids, and that’s not fair.”

The St. Louis Post Dispatch last week featured the Missouri Amish people by focusing on the recent immigrants to Schuyler County. At first, when the Amish started buying farms and moving in, many residents were suspicious, though others were evidently welcoming.

Karen Johnson-Weiner, an anthropology professor at the State University of New York, Potsdam, told the paper that Amish migrants often do not meet the cultural expectations of established residents. Amish who move to new areas are typically conservative people who are trying to maintain their traditional, rural lifestyles rather than becoming entangled in the modern, technologically-obsessed world. It is hard to understand your new neighbors, she explained, when they avoid automobiles, electricity, computers, radios, and telephones. How do established residents reach out to people who want to remain separated from others?

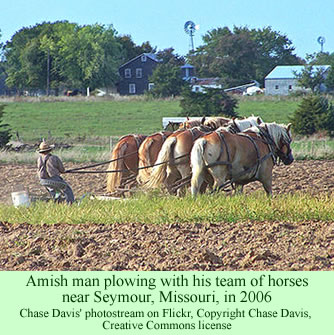

One complaint relates to the economics of the Amish farms. Robert Aldridge, the presiding County Commissioner, explained that when “English” farmers make money, they upgrade their equipment, buy new trucks, or expand their machinery. Not the Amish. They continue using the same team of horses. Since they buy so little, they don’t pay much in the way of personal property taxes to the county treasury. Residents blame them for driving up the prices of property, an inflation which prevents other young potential farmers from buying land and staying in the area.

One complaint relates to the economics of the Amish farms. Robert Aldridge, the presiding County Commissioner, explained that when “English” farmers make money, they upgrade their equipment, buy new trucks, or expand their machinery. Not the Amish. They continue using the same team of horses. Since they buy so little, they don’t pay much in the way of personal property taxes to the county treasury. Residents blame them for driving up the prices of property, an inflation which prevents other young potential farmers from buying land and staying in the area.

Missouri, the newspaper points out, has one of the fastest growing Amish populations in the United States. Out of the 250,000 Amish now living in the U.S., about 10,000 live in that state. Many immigrants settle near long-established Amish communities in Missouri, such as Jamesport, Seymour, or Bowling Green, but some have settled in Schuyler County, which has a population of about 4,100 people on the northern border of the state next to Iowa.

The reporter spoke with Henry Miller, a 43-year old Amish man who lives with his wife and nine children on their 17 acre farm near the village of Downing, Schuyler County. He said he left Wisconsin to get away from the colder winters, and he has never felt any animosity from his neighbors. “There’s not really any problems,” he indicated.

However, his neighbors, Jack and Maudie Oliver, are aware of the animosities. Mrs. Oliver is concerned about more than just the Amish opposition to fighting. While she has gotten to know many of them quite well by driving them to weddings, funerals, and shopping destinations, she is alarmed when adults leave their children to take trips. She also has problems with the burdens that their simple, technology-free lifestyle place on the Amish women.

Some of the Schuyler County “English” express their fear that the Amish practice what they feel is incest, by marrying people who are too closely related, such as second or third cousins. The Amish share that concern and try hard to avoid any incestuous relationships.

Even manure on the roads from Amish horses causes some complaints. “If I wanted manure on my car, I’d drive in a pasture,” one constituent grumbled to Commissioner Aldridge.

Gerald Robinson defends the Amish, calling complaints against them “trash talk.” He explains that not everyone is receptive to him because of his own Christian faith, but that doesn’t matter to him. Referring to the Amish, he says, “their belief is their belief. That’s what our freedom is.” Prof. Johnson-Weiner has the same reaction. When told of Mrs. Oliver’s opposition to pacifism, Johnson-Weiner replies, “That’s the problem when you enshrine religious freedom in the Constitution. Some people take you up on it.”

Another Amish man, who didn’t want to have his name publicized, owns a large farm near Queen City, in Schuyler County. He moved to northern Missouri from near Fort Wayne, Indiana, five years ago. He sold 80 acres in Indiana in order to buy a 300 acre farm in Missouri. He wanted to escape the strictness of zoning laws, city life, and an inappropriate environment for raising children. “Living around a whole lot of wealth is not good for Christians,” he told the reporter.

He explained that the Amish do, in fact, pay property taxes, contrary to popular, persistent stories, but they do not pay into the social security system since they never will collect any money from it.

Local resident Virginia Griswold feels the Amish are probably friendly, but she observes that they simply want to be left alone. But Commissioner Aldridge noted that attitudes are changing. At first, many local people complained about the newcomers, but now they stop and buy produce at their farm stands and chat.

Lorraine Austin, editor of the Schuyler County Times, a weekly newspaper published in Glenwood, says that the complaints she heard when the Amish first arrived have mostly dissipated. “It’s the flow of life. They’re here. They’re good people. They’re just accepted,” she told the reporter from the Post Dispatch.