Tashi Dolma, describing the importance of Ladakhi beliefs in a news story last week, writes that the strength of locals to tolerate the geographical and climatic extremities of their land often leaves visitors flabbergasted. Carried by the South Asian news service ANI, Dolma’s report praises the “age old beliefs of Buddhism,” the colorful prayer flags, the vast expanses of cold, high mountain deserts, and the traditional knowledge of the Ladakhi people.

But the primary thrust of the article is the danger to the traditional Ladakhi culture from the booming tourist business. Ladakhi elders are especially concerned that their cultural traditions are being forgotten. They are starting to preserve the best of the older ways and to restore as much as they can. They understand the wisdom of their natural and cultural heritage and are trying to pass it on to the younger people, who are captivated by the allures of alien cultures.

But the primary thrust of the article is the danger to the traditional Ladakhi culture from the booming tourist business. Ladakhi elders are especially concerned that their cultural traditions are being forgotten. They are starting to preserve the best of the older ways and to restore as much as they can. They understand the wisdom of their natural and cultural heritage and are trying to pass it on to the younger people, who are captivated by the allures of alien cultures.

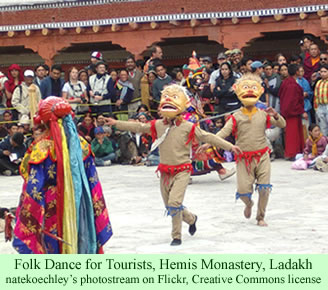

In addition to the traditional folk songs and dances, performed frequently for appreciative audiences of tourists, elders have revived older forms of theatre productions, which seem to attract younger Ladakhis. The youth are adding their own ideas to the performances, which serve to connect them with the traditions of their society.

Also, inviting people from remote communities into Leh to perform at festivals for the tourists is having the effect of encouraging an appreciation for the diversity of Ladakhi cultural expressions. Dolma argues that this trend is developing a sense of responsibility among Ladakhis for preserving their diversity.

Groups of Ladakhis are being formed to visit the ancient gompas and other historical sites, so they can discuss their value and focus on maintaining the serenity of the places. According to Stanzing Kunzang Angmo, a young Ladakhi who is studying in Jammu, “walking down the lanes of our ancestral villages along with our grandparents and their friends, helps us understand how things have changed since their youthful days.” She explains that this process has made her ashamed at how much she has ignored the natural and cultural heritage of her land.

While decrying the debilitating changes that the influx of outsiders has brought to Ladakh, the author acknowledges the fact that tourism has also fostered crucial improvements to life in the region. The balance between appropriate development and preserving the best of the past “lies in the warm hospitality of the Ladakhis,” Dolma asserts.

He concludes that the local people as well as visitors need to remain appreciative of the indigenous Ladakhi heritage in order to retain “the peace it offers … in the lives of the people…”

Three days later, other news sources indicated that Nawang Rigzin Jora, the Minister of Tourism for the State of Jammu and Kashmir, of which Ladakh is a part, announced that the state is going to mount a new initiative to promote the Leh/Ladakh region as a “mega tourist destination.” He said that the national government in Delhi had approved Rs 22-crore (US$4.489 Million) to begin the construction of a Trans-Himalayan Cultural Centre to be built in Leh. It will have galleries devoted to crafts, traditional customs, Ladakhi culture, the silk route, and Western Tibetan Buddhism, as well as a meditation hall.

The Minister added that shopping kiosks would be included as well as toilet facilities, a parking lot, internal roads, and landscaping. He made it clear that he expected all concerned agencies to cooperate in helping this project move forward as quickly as possible.