Asked if the community would take a united stand against the shale gas industry, the Amish man slowly shakes his head. “We try to avoid conflict,” he tells his visitors. A short ways behind his farmhouse, a hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, rig has been making loud thudding noises around the clock for weeks, disturbing the peaceful family with nine children that bought the property and settled in rural Lawrence County, western Pennsylvania, 18 years ago.

Elizabeth Royte, the author of a January Web Exclusive article in OnEarth, the environmental magazine of the Natural Resource Defense Council, focuses her piece on the threats that fracking the Marcellus Shale formation pose to the air, water, and quality of life for rural residents of Pennsylvania. She accompanied a local environmental activist around the county recently to find out what is going on as the controversial fracking expands. Lawrence County, near Youngstown, Ohio, had only 26 wells as of June 2012, a small number compared to Washington County further south in western Pennsylvania that has 1,795 wells, or Bradford County, in northeastern Pennsylvania, which has 896.

Elizabeth Royte, the author of a January Web Exclusive article in OnEarth, the environmental magazine of the Natural Resource Defense Council, focuses her piece on the threats that fracking the Marcellus Shale formation pose to the air, water, and quality of life for rural residents of Pennsylvania. She accompanied a local environmental activist around the county recently to find out what is going on as the controversial fracking expands. Lawrence County, near Youngstown, Ohio, had only 26 wells as of June 2012, a small number compared to Washington County further south in western Pennsylvania that has 1,795 wells, or Bradford County, in northeastern Pennsylvania, which has 896.

The issue for the rural residents of Pennsylvania is not only the noise from the massive drilling rigs, it is also the air and water pollution the drilling generates, and the disruption and noise from thousands of large trucks traveling local roads to get to the drilling sites every day. Some rural residents, as Ms. Royte finds out, are quite enthusiastic about the drilling—especially those who have sold off leases and made a lot of money. Others are heatedly opposed. The Amish quietly side with the opposition, for the most part.

Along with local environmental activist Carrie Hahn, the author visits Fred Kingery, a financier and the owner of a 100 acre tract of land directly across the road from Ms. Hahn’s house. Mr. Kingery does not live on the property on which he has sold a gas lease. Justifying his gas lease sale, he denies that combustion of hydrocarbons is warming the earth, and he argues that further development of shale gas resources from the Marcellus formation will help America achieve greater energy independence.

Hahn tells him abruptly that her house, her property, is screwed if a drilling rig were to be erected across the road from her. “I wouldn’t want one across from my house either,” he admits, “but that’s just how it is.” He adds, “It’s not about the money. It’s all about energy independence.” He goes on to say that the noise and disruption of the energy extraction process is all a necessary part of progress.

The 400 Amish families who live around New Wilmington, in Lawrence County, are mostly opposed to the drilling, but some are ambivalent because they sold gas leases on their land long before the fracking boom started a few years ago. Instead of the $3,500 per acre that current land owners are getting for signing leases, they got $3.00 per acre. Yet those leases, which the land owners thought meant only the small drilling rigs of the time, evidently also give the companies the right to come back and erect much larger, more intrusive, drilling pads for the fracking process.

Fracking involves drilling straight down a mile or so into the Marcellus Shale formation, then turning the hole on a right angle, and drilling for thousands of feet horizontally within the Marcellus. Then, the driller pumps a water/sand/chemical fluid mixture into the well at high pressure to fracture the rocks, allowing the trapped gas to flow out along the pipeline.

Opponents contend that the drilling fluids contain many dangerous chemicals that could harm the ground water and that the process also releases harmful pollutants into the air. Industry sources deny those dangers. The money, along with the noise and pollution, that the drilling brings into rural Pennsylvania and some nearby states, divides communities.

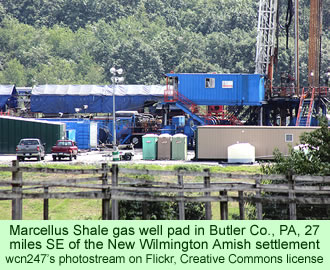

Ms. Hahn visits one Amish farmer whom the author calls Andy Miller, a pseudonym. He sold off his gas drilling rights many years ago for a pittance, and now he is faced with the possibility of big drilling pads on his land. The new drilling pads would be several acres in size, and would include a lot of equipment and noise—large drilling rigs, storage tanks, compressors, pipes, flare towers, diesel generators, office trailers, and the like. Plus, drilling pads are serviced by up to 1,000 large trucks per day. A quiet rural forest or farm field is transformed into an industrial zone.

Mr. Miller sold his rights to Atlas, a company that was bought up by Chevron in 2011. He admits he has used the money he made from his gas lease to pay for some things he needed, such as new drainage tiles in his fields. But he is opposed to the threatened additional developments. “We don’t want huge gas companies coming here because of the heavy pollution, the traffic, and so much money,” he tells Hahn and the reporter. “When money rules, a lot of bad things happen to a community,” he concludes.

Atlas drilled a small, shallow, gas well some years ago, but, surprisingly, Mr. Miller has managed to keep the Marcellus Shale gas developers at bay. He denounced a gas company representative who tried to visit his property on a Sunday. He refused another his permission to gain access to his land to conduct seismic mapping, evidently a process that he has no obligation to allow. Ms. Royte writes that she pressed him to explain how he could legally deny access to the representatives of the gas drillers, but the Amishman avoided answering the question.

As in all such controversies, human motivations are often confused and conflicted. The journalist points out that while it is tempting to contrast the low-tech Amish with the high-tech drilling pads, the issues are not so simple. The Amish make individual decisions about their lands—so long as they don’t violate the Ordnung and community moral standards.

They have expenses and taxes to pay, like everyone else, and they are often tempted by the stories and promises of the landmen who try to talk them into signing leases. And they can feel the usual emotions toward others who waited a few years and got a thousand times more per acre.

The Natural Resources Defense Council launched a Community Fracking Defense Project last year to provide policy and legal help to local governments in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, North Carolina, and Illinois that want to try and control the development of shale gas drilling. This current article in OnEarth, with its interesting focus on the Amish, gives an effective overview of the hazards to rural America from the shale gas boom.

Royte, Elizabeth. 2013. “Fracking the Amish.” OnEarth. January 10, 2013. http://www.onearth.org/article/fracking-the-amish. Accessed January 21, 2013.