A committee writing a new constitution for Egypt has banned forced evacuations, like the one 50 years ago that destroyed most of Old Nubia. According to a news report last week, Hoda Al-Sadda, chair of the Rights and Liberties Subcommittee, indicated that the measure is aimed at protecting minority groups—not only the Nubians from southern Egypt but also the Bedouin people of the Sinai region.

The chair of the full, 50-member committee, Amr Moussa, confirmed the intentions of his group to make the constitution broadly inclusive: “This constitution will be new in the sense that it will be aimed to serve the interests of all Egyptians, rather than the 2012 Constitution that was tailored to serve [solely] the interests of the Muslim Brotherhood.”

The chair of the full, 50-member committee, Amr Moussa, confirmed the intentions of his group to make the constitution broadly inclusive: “This constitution will be new in the sense that it will be aimed to serve the interests of all Egyptians, rather than the 2012 Constitution that was tailored to serve [solely] the interests of the Muslim Brotherhood.”

Moussa added that the new constitution will be completed by the end of November. He will then forward the document to Interim President Adly Mansour, who will place it before the Egyptian electorate in a national referendum.

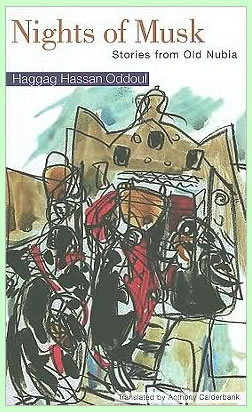

Another news report, posted to the Internet early last week, explored in greater detail the way Nubians are advocating their interests in the constitution-writing process. The article is based on an interview with famed Egyptian writer Haggag Oddoul, author of a prominent volume of short stories, translated into English as Nights of Musk. Oddoul is serving as one of the 50 members of the constitution committee.

He provided some background about himself. Though born in Alexandria, where he lives to this day, Oddoul is proud of his Nubian heritage. Both of his parents moved north to Alexandria from their village in Nubia. Before he became a writer, Oddoul did construction work and served in the Egyptian army during the 1967 and 1973 wars. He views Nubian relationships with Egypt as one of “rapprochement rather than separation.” He said he appreciates the value of ethnic and racial diversity, and of harmony among peoples.

When he began writing about Nubian issues, he found himself becoming a leadership figure, a role he didn’t necessarily seek. He said he was the one who applied the phrase “right of return” to the Nubian people, exiled from their native lands in southern Egypt due to the construction of the Aswan Dam, yet deserving of the right to move back to the Upper Nile valley. That phrase has potent meaning in the Middle East, where Palestinians forced out of their homes feel they too should have the right of return to their native lands.

He said his activism made him subject to backbiting and criticism, so several years ago he decided to focus his energies on writing his next book. His attitudes changed, however, after the Egyptian Revolution over two years ago. He supported the work of activist Manal el-Tibi, who was the only Nubian member of the committee writing the constitution last year. She attempted to represent their interests, but she resigned due to the animosity of the Muslim Brotherhood majority on the committee toward minority groups.

Oddoul (his name is spelled Adul in last week’s news article) attempted to champion other leading Nubians, such as el-Tibi, for the Nubian seat on this year’s critically important constitution committee. However, he found that he was very widely supported as the favored representative of the Nubian community at large.

He told the journalist that the committee is working in a reassuring, consensual fashion, and he is trying to champion Nubian interests to the full committee in the same way. He keeps a supportive team of other Nubians constantly informed of the issues being discussed by the committee, and he represents their views to it.

Oddoul sees himself as acting in three different capacities. First, he serves on the committee as a citizen of Egypt, someone who has been in the armed forces of his country. Secondly, he serves in the capacity as a Nubian activist and thirdly as a creative writer. He integrates those three roles in his own thinking.

He believes in the importance of Nubian integration within Egyptian society, and disagrees with Nubian separatists. He strongly emphasizes his argument. “We are smart, and we are calling for additional integration, not more isolation.” He does not expect that there will be specific articles in the new constitution dealing with Nubian issues. But he is working with others to make sure that there will be constitutional provisions protecting ethnic and cultural pluralism in their country.

He warns of the impatience of younger Nubians for the recognition of their rights. “Some have said that Egypt, which does not take our rights into consideration, is no longer our country,” he said. “Thus, it is necessary to develop solutions to counter this growing discourse.” The first solution is obviously the development of a fair constitution that encourages respectful exchanges and equitable solutions to problems such as the historic discrimination suffered by Nubians.

Oddoul mentioned how his suggestions in the past about promoting the Nubian people and their culture have been ignored by Egyptian authorities. For instance, he suggested to Farouk Hosny, the former Minister of Culture during the Mubarak regime, that an African cultural festival should be organized at Abu Simbel, the famous temple complex in southern Egypt south of Aswan.

He saw this as a way of promoting Egypt’s connections with the rest of Africa. Such a festival would have spotlighted the Nubian people, of course. Hosny supported the idea, but the rest of the Mubarak government was negative to the suggestion, so it got nowhere.