The village of Cape Dorset on western Baffin Island enthusiastically supports its Inuit artists, some of whom have a reputation of producing world-class art. Two years ago, the artists in the community were covered in a college newspaper, and last week they were the subject of a feature story in the major international news source, Al Jazeera.

The reporter who visited Cape Dorset focused on the creativity of the artists. They draw and sculpt walruses, seals, whales, polar bears, and other animals, but they often introduce mythic elements as well as fine natural details to their works. An owl or a goose may be depicted with finely drawn feathers, but a frog may have the hands and head of a man and the soul of a monster.

The reporter who visited Cape Dorset focused on the creativity of the artists. They draw and sculpt walruses, seals, whales, polar bears, and other animals, but they often introduce mythic elements as well as fine natural details to their works. An owl or a goose may be depicted with finely drawn feathers, but a frog may have the hands and head of a man and the soul of a monster.

Bill Ritchie, manager of the Kinngait Studio, which is part of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-op, said about the art works that he exhibits, “when you see this work hanging on a wall, it’s not what you expect. It’s new, provocative, edgy and often joyful.” He sees his role as an art dealer as making sure that the best art productions get into the hands of buyers farther to the south, and that the talented artists are richly rewarded for their creativity.

The Al Jazeera journalist visited the Kinngait studios, on a side street of Cape Dorset, and observed several artists working in back rooms. Shuvinai Ashoona was in one room hunched over a drawing pad. She is considered a cutting edge artist for drawing such scenes as a woman giving birth to a monster.

Jutai Toonoo works nearby. He used to be a sculptor, but he lost some fingers in an accident so he has turned to drawing instead. He is working from a cell phone photo he took of a small wildflower wilting under a crust of new snow. He says that, in the Arctic, one has to look closely at the land to find things to draw since there are no trees.

“When you look really close, sometimes there’s a forest of plants, tiny plants. And that’s what I like to draw. Today, anyway.” He views his drawing as “a crazy form of healing” that allows him to get his feelings out on paper.

Pitaloosie Saila in the next room is busy signing a pile of her prints. Speaking in Inuktitut, she tells the journalist that she is proud of the fact that many of her works are on display in the cities to the south. It is important to her that they are making people happy. She likes the fact that outsiders are learning from her works how the Inuit live and what they do.

Tim Pitsiulak’s work adorns a 25 cent Canadian coin, and his creations hang in boardrooms in major cities. But he says he’s really a hunter at heart. He shows Al Jazeera a photo on a computer screen of a walrus that he shot just the previous week. Then he shows off pictures of his 19-year old son, who just shot his own first walrus.

But his art expresses his visions of the animals. He includes legendary themes, showing creatures that are half animal and half human, or animals that have human clothing on them. Pointing to one drawing, he says, “that one is a sea monster that lives under the ice and drags people into the ocean. That was fun to draw.”

Bill Ritchie, the manager of the studio, praises the artists and adds that the younger ones are more fortunate than their elders. The older artists could only speak Inuktitut, while the younger people are also fluent in English, so they can speak for themselves. “That opens a whole new world to the younger ones,” he believes.

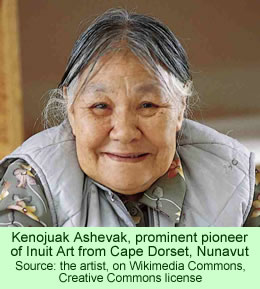

An annual offering of Cape Dorset prints this year featured 32 works from 11 artists, including seven from the late Kenojuak Ashevak, one of the most prominent Canadian artists of recent years. She died in 2013, a “Canadian national treasure.” She was famed for her sculptures, paintings, and prints—and as a leading citizen of Cape Dorset.