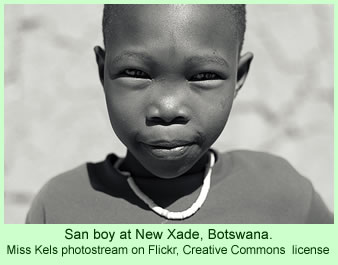

Last week the BBC published a moving story about living conditions in New Xade, a resettlement camp to which the G/wi were relocated by the government of Botswana. They were forced by government agents 16 years ago to load their belongings and themselves onto the backs of trucks, which took them to their new village. The trauma of the move clearly still haunts the G/wi and the other San people who were required to leave their homes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR).

The BBC reporter, Pumza Fihlani, talks in New Xade with two women, Boitumelo Lobelo, 25, and her younger sister Goiotseone Lobelo, 21. Both are doing laundry and caring for their toddlers as the reporter speaks with them.

The BBC reporter, Pumza Fihlani, talks in New Xade with two women, Boitumelo Lobelo, 25, and her younger sister Goiotseone Lobelo, 21. Both are doing laundry and caring for their toddlers as the reporter speaks with them.

They remember the relocation vividly. “The police came, destroyed our homes and dumped us in the back of trucks with our belongings and brought us here. They dumped us here like we are nothing,” Goiotseone says. The women were just girls when the police came, but they well remember the enjoyable aspects of their former lives, such as joining older women in the bush collecting roots, nuts, and berries to eat.

They have been back to their former home site numerous times, but they’re not allowed to live there. A court decision in 2006 appeared, at first, to be a victory for the San people, granting them what they had requested—the right of return to their homeland inside the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

But the government subsequently decided that the court ruling only would apply to the litigants whose names actually appeared on the court suit, not to their wives and children or other members of the San societies. They have to make separate applications in order to be permitted to make brief visits.

The Lobelo sisters become angry describing living conditions in the resettlement camp to Ms. Fihlani. Boitumelo tells her, “we are getting AIDS and other diseases we didn’t know about; young people are drinking alcohol; young girls are having babies. Everything is wrong here.”

The reporter relates stories of government oppression against the peaceful indigenous people, but she provides readers with the government argument that the relocation was justified in order to protect the wildlife and natural ecosystem of the CKGR. She writes, however, that the G/wi and the other San peoples had subsisted sustainably in their traditional desert homes for millennia on hunting and gathering.

Ms. Fihlani says that diamond mining is about to start in the reserve, after years of preparations. She writes that the government has always denied any connection between the forced relocations and the diamond industry, though she does not mention that former Botswana President Festus Mogae as much as admitted there was such a connection in a speech in Mumbai in 2005.

The tragedy for the G/wi in New Xade is that they have not learned how to live as herders. When they were dumped at their new home sites, each family was given five cattle or goats, which it was assumed would encourage them to become pastoralists rather than continue to be hunters and gatherers.

Their problem has been that they don’t have the knowledge to take care of herd animals effectively. According to Jumanda Galekebone, a spokesman for the group, “if you push somebody to a certain kind of lifestyle that he doesn’t know, he will be facing a lot of difficulties.”

He explains that the people don’t really understand how to take care of their animals when they get sick. Along with some other people sitting under a thorn tree, Mr. Galekebone elaborates on their woes. Modern life has simply not worked for them, and they want to go home.

Mr. Galekebone explains that life for the San people in New Xade hasn’t helped anyone. “We still get a lot of people going inside the park to hunt and they get arrested. Some of us here are facing court penalties for hunting. It just proves that you can’t force change on people.”

Roy Sesana, another San leader, is one of the people whose name was on the 2006 court papers, so he is allowed to live at his original home in the CKGR. But his family is not—he must travel to New Xade to be with them. “We have been separated from our children and our wives,” he says. “What kind of life is this? We didn’t do anything to deserve this.”

He continues, angrily, decrying the government food handouts as an affront to people who have always provided their own food from the bush. “We are being made lazy and stupid,” he says. “Now we are being treated like dogs.”