The Digital Journal, an Internet news service based in Canada, published an opinion piece last week about a British Library project to archive in digital format the artifacts of written Lepcha culture. Fortunately, the story provides a link to the British Library website where one can find more information about the project and the actual texts of the documents themselves—for those who can read Lepcha.

The project is based on the conviction that it is important to save, through digital means, publications in rare and endangered scripts, where the languages and cultures are threatened with being forgotten and lost. Dr. Heleen Plaisier has devoted a lot of scholarly effort to Lepcha language, culture, and bibliography, and she has been the driving force in digitizing the Lepcha works for the library. She has a PhD from Leiden University and now has a position as a visiting scholar at the University of St. Andrews.

The project is based on the conviction that it is important to save, through digital means, publications in rare and endangered scripts, where the languages and cultures are threatened with being forgotten and lost. Dr. Heleen Plaisier has devoted a lot of scholarly effort to Lepcha language, culture, and bibliography, and she has been the driving force in digitizing the Lepcha works for the library. She has a PhD from Leiden University and now has a position as a visiting scholar at the University of St. Andrews.

The British Library website gives an effective perspective on the scope of the Lepcha project. It indicates that many Lepcha are losing interest in their own language and are beginning to forget their traditions and culture since they are now a small minority in their native Sikkim.

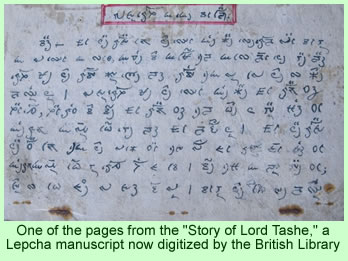

The written Lepcha language was developed in the 18th century. It is still used in textbooks published by government agencies and in privately published magazines and journals that consciously are trying to keep the language and culture alive.

The manuscripts that the British Library has digitized represent artifacts that will, hopefully, also help to preserve the cultural traditions of the Lepcha people. Many of those texts identified for preservation so far were written in the second half of the nineteenth century. A lot reflect Buddhist interests, but some incorporate older Lepcha traditions. The project, in the words of the website, “is expected to shed light on the nature of indigenous Lepcha religious beliefs and the spread of Buddhism in the area.”

Dr. Plaisier indicates that she has gained access to a number of collections in both Sikkim and, to the south, the Darjeeling District of India’s West Bengal state. Families have allowed her to see and study unique Lepcha manuscripts in their private archives. In one case, she saw a collection of 30 manuscripts in a single house; in others, one or two manuscripts. She believes that about 10 Lepcha families around Kalimpong hold one or two manuscripts each.

But the collections are not just held in the hands of families. The privately owned Lepcha Museum in Kalimpong is believed to own approximately 60 Lepcha manuscripts. Dr. Plaisier’s grant from the British Library was intended to promote the recording and digitizing of these priceless manuscripts. The Namgyal Institute of Tibetology in Gangtok in Sikkim is the local institutional partner for the project.

The grant-holder writes that many of the original manuscripts are very fragile. They are written on paper and have suffered from insects, moisture, and smoke damage. Although the owners may try to care for their artifacts, many do not have the means to archive them properly in climate controlled conditions for long-term preservation. Many Lepchas have lost interest in their cultural heritage, which makes the preservation of the heirlooms of even greater importance for those who really are trying to keep alive their written language.

The project has resulted in 40 Lepcha manuscripts becoming fully digitized, copies of which are deposited in the British Library and the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. The manuscripts can also be studied through links on the website to each of the different collections, and then to the actual manuscripts within the collections. The survey identified seven collections with 155 manuscripts, plus two further collections holding about 120 additional works.

Beyond that, at least two additional collections may hold approximately 420 more manuscripts. Dr. Plaisier learned, in the course of her study, that it may be difficult to gain access to those collections, even in the interests of preserving them for future use by Lepcha students and scholars. “During this project it became obvious that many Lepcha manuscripts are zealously protected both by their owners and by socio-cultural organisations from interference by outsiders,” she writes.

Unfortunately, unrest both in Sikkim and in the Darjeeling District of West Bengal brought her project to an early close and forced the cancellation of a second research trip.