One would expect members of the peaceful societies to spread out, establishing family groups and communities in new locations, moving and settling elsewhere just as many other people do. Tristan Islanders resettle in Cape Town, some Inuit have moved south to major Canadian cities, and a group of Hutterites established a colony in Japan.

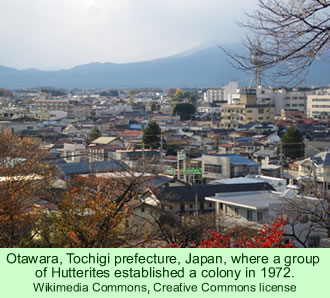

Hutterites in Japan? An article on the subject last week in the Japan Times, a daily English-language newspaper from Tokyo, was intriguing. It seems as if a group of four Japanese Christians, who evidently had adopted the Hutterite faith and culture, moved to Tochigi Prefecture and settled there in 1972 near the town of Otawara, about 165 km (102 miles) north of Tokyo. It is near the main Tohoku railroad north toward Fukushima.

The original settlers were greeted by a fair amount of hostility from the traditional Buddhist and Shinto people of the community, so they were only able to acquire a small amount of land at a time, located well outside of town.

The matriarch of the colony, Mariko Kikuta, told the visiting reporter that the residents of Otawara didn’t want them to settle nearby, “and nobody would sell us the land we needed, so we ended up way out here.” She added, “at first there was no water or electricity here, and we had some people come and throw stones at us, so we really had a hard time.” They were able to slowly buy up additional land so they now own 2.5 hectares (6 acres).

The colony attracted more members as it grew in area, and it reached a population of 40. Almost entirely self-sufficient, they built their homes, grew their own food, and constructed other essential buildings: a church, a community dining and social hall, and massive coops for the colony’s growing flocks of prize chickens.

The colony raised funds through the sale of chickens and eggs—the supermarket chain Seijo Ishii started selling their products. In addition to the eggs and chickens, the colony grew plums, kiwis, and raspberries, which they processed into jams. In the winter, they switched to other fruit crops such as grapes, cherries, and persimmons, and grew Chinese cabbages and broccoli.

The people ate communally in the dining hall, and attended church services four times per week. The hand-hewn pews in the church face a large plate glass window that looks out onto a hillside. The colony was led by Fumio Kikuta, who was aided by other senior male residents. It received visitors—Hutterites and Mennonites—from abroad.

But things began to decline in the mid-1980s. Young people lost interest in remaining in Otawara. The four sons of the Kikutas, all raised in the colony, now live in Tokyo and work at prominent Japanese firms. None have any interest in returning to Otawara.

To add to their problems, Mr. Kikuta had a stroke in 2007, and while he lives at the colony, he lacks the vigor of his youth. Then, the great Japanese earthquake of 2011 struck. It moved the colony’s bread-making machine off its foundation. It is no longer operational.

Because of the fears of radiation exposure, Seijo Ishii cancelled its contract with the colony for its prize eggs, depriving the Hutterites of its remaining source of outside funds. Since Mr. Kikuta is mostly confined to his home, the other four residents, aging women, have to handle everything.

Two of the women treat the reporter, Mark Buckton, to herbal tea plus a simple meal of toast and salad before he leaves. He asks if publicity might help turn things around for the five remaining Hutterites. Mrs. Kikuta replies, “People must come of their own accord to Hutterite colonies.”