Daniel Koehler has published three more installments in his blog about his filming adventures among the G/wi and G//ana San people of Botswana.

His blog post published on April 22 described a trip he took from New Xade, the resettlement town he has been living in, out to the traditional community in the desert called Metsiamanong, located in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. He described an earlier visit to Metsiamanong in January 2015.

He and his assistants had left New Xade intending on driving to the traditional settlement so he could do some more filming as part of his Fulbright National Geographic Fellowship project. He is producing a film on the G/wi and the G//ana people, both in their traditional desert life and in the more modern resettlement community of New Xade, located to the west of the CKGR.

He and his assistants had left New Xade intending on driving to the traditional settlement so he could do some more filming as part of his Fulbright National Geographic Fellowship project. He is producing a film on the G/wi and the G//ana people, both in their traditional desert life and in the more modern resettlement community of New Xade, located to the west of the CKGR.

The transmission in the truck they were driving began banging ominously, shortly after they crossed into the CKGR. Then the truck simply stopped. Mosodi, one of the people with him, announced that it was the gearbox. Someone said it was 45 kilometers, or 27 miles, to Molapo, the nearest San community of any size where he could seek help. Since there was no cell phone service in the desert, and he apparently didn’t have a working satellite phone, he and Kitsiso, a friend who was with him, decided to walk across the desert to seek help. It was either that or wait in hopes that someone might come along the rarely-used road.

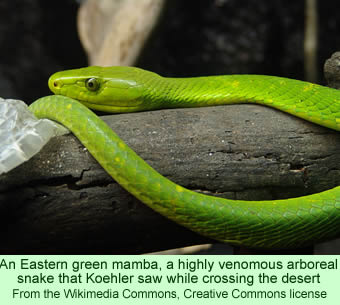

As the two men trudged along, they saw lots of wildlife, including antelope, squirrels, a fox, and a green mamba slithering along the branch of a tree. They appreciated the beauty of the desert, and Koehler enjoyed not having the burden of carrying a camera. It was an opportunity to walk along and enjoy the desert. However, he writes that he was hoping to make it into Molapo before nightfall when the lions and other desert predators would become more active.

When they ran out of water in the bottles they were carrying, they found a puddle that had not dried up from a rain earlier in the day. Kitsiso taught him to gently blow on the surface of the water to clear the dirt away before drinking. They arrived in Molapo safely later that night. He writes that he learned flexibility during that trip—and repeatedly throughout his filming experience in Botswana.

Koehler’s blog post of May 15 focuses on a young San man whom he had met and introduced in an earlier post, named Ketelelo. The man had decided that getting an education was to be his future, and he had clearly worked hard, despite many obstacles, to achieve it. He described to Koehler the impression of hopelessness among many of the San in New Xade, people who have no dignity, no identity, and no land.

Ketelelo had decided that his future did not lie with hunting and gathering as his ancestors had done—his goals were to be reached through education. Koehler’s quote from the words of Ketelelo are dramatic: “‘We are not primitive,’ He told me with a glimmer in his eyes. ‘We are people with hopes. We are people with dreams. If opportunities can be unveiled in front of us, we can take them.’”

During his visit to New Xade, Ketelelo showed the author a stack of certificates representing academic honors he had been awarded. He told the American that education was the way for the San to improve their housing and food shortages, to solve drug and alcohol abuse issues, and to better their lives in general.

While other San have run into numerous obstacles in their paths to obtaining some education, Ketelelo firmly expressed his conviction to Koehler about its importance. He was the first San person to graduate at the head of his class at the senior secondary school. He is optimistic that he won’t be the last.

Koehler’s most recent blog post, published on June 27, summarized the major aspects of his long stay among the San. He wrote that he would be returning to the U.S. shortly to be part of some orientation programs for next year’s crop of Fulbright National Geographic fellows. But he will then return to Botswana for a couple more months to finish editing his film.

That last essay is quite graceful. He describes his indebtedness to his friends Ketelelo, Kitsiso, Opaletswe, and others. He acknowledges the work of his assistant, translator, and field producer, Kebabonye, with whom he has been working hard on a pair of laptops to put together and edit over 300 hours of filming into what is shaping up into a 45-minute working draft of a documentary film.

He urges readers to keep a watch out for a new Facebook page for the film when it is ready for distribution, as well as for a preview of some footage from the documentary he is in the last stages of producing.