Researcher Samir Bukab maintains that Nubian music has 12 rhythms, which inspire different meanings for different listeners, though none are symbolic of the warfare that is common among other Sudanese societies. His comments appear as part of an article on the music of the Nubian people of northern Sudan and its importance in their society. It appeared last week in the Sudanese news magazine SudaNow.

Mr. Bukab also told the journalist, Ishragah Abbas, that Nubian rhythms are derived from natural sources—birds, the plough, the rustling of leaves on the date palm trees, the waterwheel, and the waves of the Nile. Nubian dances derive from similar sources: a dance that is like the movements of the nightingale, or another which imitates waves in the river.

Mr. Bukab also told the journalist, Ishragah Abbas, that Nubian rhythms are derived from natural sources—birds, the plough, the rustling of leaves on the date palm trees, the waterwheel, and the waves of the Nile. Nubian dances derive from similar sources: a dance that is like the movements of the nightingale, or another which imitates waves in the river.

He added that the words and phrases of Nubian songs describe and resemble the local environment and are free from obscenities, in accordance with the ethical values of the Nubian people. They also have songs about decorating with Henna and songs for women that are improvised and played during celebrations such as weddings. They sing political songs that are critical of the government of Sudan, and that state the opinions of the people about the construction of more dams that will have an impact on them.

Several individuals interviewed by Ms. Abbas, including Mr. Bukab, indicated that Nubian music had been suppressed from radio and television broadcasts for a number of decades due to the Arabization of Sudan, but recently a revival of interest in the ancient art form has taken place. Many songs are now being recorded and broadcast, and the Sudanese people in general, as well as just the Nubians, are listening and enjoying them.

Dr. Graham Abdul Gadir, a music scholar, told the author that the revival of Nubian singing is revitalizing the heritage of Nubia. It is encouraging the people to maintain and treasure the values of their ancient civilization, as well as serving to help preserve their language. Furthermore, the growing popularity of the Nubian songs among the people of Sudan is helping strengthen the unity of that nation, Abdul Gadir maintains.

Fatima Abbas, a Nubian woman from Dongola, a town on the Nile River, told the writer that she is proud of their culture and particularly of their tradition of singing. She said that while she did not have any Nubian songs sung at her wedding, she has changed her attitude; she organized singing at the wedding of her son. Another son will be married this year and again she wants there to be a similar evening of singing. “I want to make my sons and their friends, even the non-Nubians, to be aware of, and enjoy this gleeful singing which the new generations are not aware of,” she told the journalist.

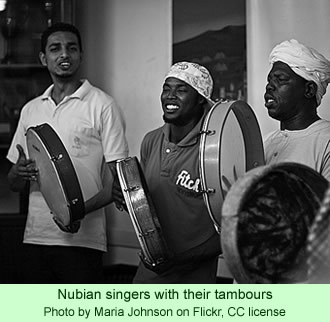

She said that even when she hears just the rhythms of the tambour, the traditional drum, it makes her feel an intense yearning and nostalgia. The music reminds her of people who are not with her, and of her distant relatives. The singing reminds her of rural Nubian life—their farming, their conversations, and their love for one another. “When I hear those songs I feel as if I am among them, something which makes me feel very happy,” the housewife said.

The singer Dawlah Atta said many of the same things to the writer. When he performs at parties, he notices that listeners to his Nubian songs seem to achieve a surprising state of exultation. He feels that is because the Nubian singing evokes emotions due to the rhythms, which are inspired by nature. They link the listener harmonically to the natural environment. He also ascribes these emotions to the words of the songs, which express the good times of the past and which invoke pleasant memories.

He added that the rhythms used in the songs will prompt even non-Nubians to start dancing. He recalled an incident when a Swiss man and his wife started dancing when he was performing in the national theatre in Omdurman, a major Sudanese city across the river from Khartoum.

However, Abu Zar, a young Nubian man, expressed some reservations about the revival of their music. He said that while it is appropriate for people to revive their heritage, it must not lead to tribalism that threatens the establishment of the modern nation of Sudan. A journalist named Abdulla al-Haj disagreed. He said that listening to the traditional music represents a potentially valuable self-searching mechanism.

He illustrated his argument by describing the exile of Nubians when the Aswan Dam was built, from the Wadi Halfa into the Khashm al-Girba region in East Sudan. The exile caused a shock to their culture, music, and songs, which expressed feelings of estrangement and calamity that they have transmitted to their children. However, he said, a new generation of Nubians in Sudan is listening to their stories and songs which remind them of their roots. The songs are inspiring some of the young people to form groups that are trying to revitalize their heritage.

Discussions of music and dancing appear in various sources on Nubian society, among them Elizabeth Warnock Fernea’s (1991) description of the elaborate ceremonies, including a lot of singing, during a traditional wedding celebration (p.79-93). Jennings (2009, p.78-81) also describes a Nubian wedding that included a lot of singing. A YouTube search for “Nubian Singing” yields many videos of their music being performed in Egypt and Sudan.