Gregori, a grandson of the elderly shaman José Antonio Bolívar, tells the reporter, in the words of Google’s translation, “yopo is our diamond and we are here to share the highlights.” The Piaroa man adds that his grandfather can use his drugs as medicines to cure diseases, to cause pregnancies, and to purify people’s souls.

For decades, the ancient healer and his family have welcomed travelers such as a French reporter to his compound near Puerto Ayacucho, the capital city of Amazonas State in Venezuela, where they can experience hallucinogens with a master of the art. While the Piaroa believe in sharing everything within their communities, the journalist, Simon Pellet-Recht, indicates that the grandfather nonetheless charges travelers for the drug trips. A report about his experience appeared last week in Libération, a daily French newspaper.

For decades, the ancient healer and his family have welcomed travelers such as a French reporter to his compound near Puerto Ayacucho, the capital city of Amazonas State in Venezuela, where they can experience hallucinogens with a master of the art. While the Piaroa believe in sharing everything within their communities, the journalist, Simon Pellet-Recht, indicates that the grandfather nonetheless charges travelers for the drug trips. A report about his experience appeared last week in Libération, a daily French newspaper.

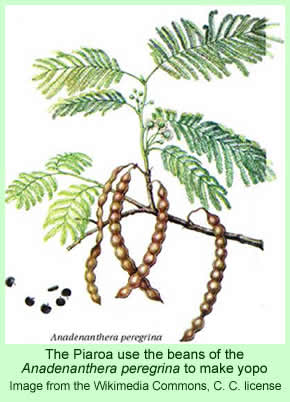

Yopo is a hallucinogenic powder made by the Piaroa from the crushed seeds of a leguminous tree, Anadenanthera peregrina. It is mixed with ash and lime and snuffed up the nose. A sign in the room where the participants have gathered insists that they should stay squatting, not shout or make sudden movements, and keep their heads down. Mr. Pellet-Recht writes that he takes only a small dosage that first evening but he feels the effects immediately.

He quickly realizes the importance of the drug to the Piaroa. It prompts them to stop and take the time to listen and think—it invites a sense of trust, he believes, because it has weakened everyone in the room who has taken it. Almost as a necessity, the drug has facilitated a sense of respect among the participants.

As the night progresses, the participants seek their hammocks to get some sleep before they awake at daybreak. The second night, the old man starts the ceremony at midnight, lying in his hammock singing for two hours. The author takes the same strength dosage of yopo as everyone else that night in order to see what happens. His hallucinogenic experiences include dreams about a swarm of butterflies and a book flying down a white corridor. He feels a fleeting sense of euphoria.

The party leaves the next morning without having had much sleep in order to go with the shaman to another community. The author was struck by the fact that the soldiers at a military checkpoint look away when the group drives up, a result of the respect in which the shaman, Mr. Bolivar, is held by everyone. He was born in 1930.

They travel that day to a community where his aunt Josefina, who was once his nurse, lives. She is over 100. Yopo is not part of her life, Pellet-Recht writes: Piaroa women have nothing to do with the drug culture of the shamans. Their lives focus on raising cassava, fishing, and the work of the day. But Shaman Bolivar is delighted to be in the village, since it is at the heart of the Amazon and of his peaceful, and pacifying, crusade.

The author writes that not all yopo drug trips are conducted by experienced shamans. It is also used in towns, where people such as tourists simply get together in houses. But this trend does not worry the Piaroa. According to Eli, a grandson of Bonivar’s who helps conduct the event, correctly utilizing yopo requires many years of experience, such as his grandfather has had.

Robin Rodd (2008) wrote about the uses of the Banisteriopsis caapi vine (ayahuasca) as a hallucinogenic drug by Piaroa shamans and he included some helpful information about their uses of yopo. He wrote that when the shamans wanted to experience especially strong visions, they would first take, orally, powerful preparations of the caapi vine. Then they would snuff yopo.

The shaman’s success in maintaining social harmony in the community depended on his ability to perceive the needs and desires of the people, tasks which strong doses of the hallucinogens seem to facilitate, Rodd argued. The shamans believe that the caapi preparation give them proper perceptions, while the yopo “delivers the subsequent visionary punch (p.304).” The duties of the shaman include such group rituals as funerals and initiation rites, plus individual ceremonies for purposes of divination, sorcery, and healing.

The two drugs, caapi and yopo, are often consumed at the same time in order to address practical problems in the community, such as advice for hunters as to where to hunt, or where to clear a swidden gardening plot, or whom to marry. The two drugs can also help the shaman figure out “how to make spouses happier, how to keep children in school or how to get along with the other members of their family (p.304).” Yopo and caapi, in other words, help maintain peacefulness in traditional Piaroa communities.