A compromise solution that might end the persecution of the G/wi and the G//ana San peoples by the government of Botswana started leaking out to the press a month ago. The government had forcibly removed the San people from their homes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) many years ago and it has denied those that have managed to stay any right to water from boreholes. It has also deprived them of their traditional hunting rights.

On January 18th, a Botswana news source reported a rumor that Roy Sesana, the leader of the advocacy organization First People of the Kalahari (FPK), was going to be taking a job with the government. He was to be employed as a project officer for the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. He will be based in Molapo, a large settlement within the CKGR where he was born. He will be helping the San people establish cultural tourism projects. In return, the FPK leader was told that the government would restore services to communities of San people in the CKGR, which were cut off in 2002.

On January 18th, a Botswana news source reported a rumor that Roy Sesana, the leader of the advocacy organization First People of the Kalahari (FPK), was going to be taking a job with the government. He was to be employed as a project officer for the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. He will be based in Molapo, a large settlement within the CKGR where he was born. He will be helping the San people establish cultural tourism projects. In return, the FPK leader was told that the government would restore services to communities of San people in the CKGR, which were cut off in 2002.

A news story in Mmegi on January 22 clarified the situation. It indicated that Sesana had taken a job with the government as part of a deal that would provide water to San communities in the CKGR. Sesana had had a private meeting with Ian Khama, the President of Botswana, to appeal for relief and services for the San. The two men had evidently reached a compromise allowing the resumption of services in return for the development of a tourist infrastructure that would showcase the traditional San cultures.

The deal has generated hostility and resentment among some of the San people, in part because they have not been adequately informed as to what their leader had agreed to. Bashi Thiitse, the area councilor for the CKGR, told the reporter that Sesana is deeply concerned about the interests of the San people, though he admitted that the fact of his having a new job with the government has left many confused as to what really went on between him and Khama.

Survival International, the human rights group based in London that has championed the San for over 10 years, took a cautiously optimistic view of the reported compromise. A representative of the organization, Rachel Stenham, indicated that the new flexibility of the government may be just a ploy for international approval that will fade once the upcoming 50th anniversary celebrations of Botswana’s independence pass in September 2016.

Survival International, the human rights group based in London that has championed the San for over 10 years, took a cautiously optimistic view of the reported compromise. A representative of the organization, Rachel Stenham, indicated that the new flexibility of the government may be just a ploy for international approval that will fade once the upcoming 50th anniversary celebrations of Botswana’s independence pass in September 2016.

Mmegi also contacted Jumanda Gakelebone, another prominent San leader, about the situation. He told the paper that he was still not sure what was going on, but he could understand Mr. Sesana’s desire to earn some money from a paid position—he “is a family man [and] he has to feed his family,” Gakelbone said. He worried that Sesana may have compromised his position as the leader of the San people just from the appearance of selling out to the government.

Keikabile Mogodu, a director of another San advocacy group, the Khwedom Council, expressed pleasure about the response by the government, and he hoped that the situation in the CKGR will finally improve. He acknowledged the questions that the people are raising, and he wondered if Sesana will be able to advocate for the San people any longer if he is viewed as a sell-out or a deal-maker. According to the news report, Sesana will act as a liaison between the government and the residents of the CKGR, initiate important issues that concern the local people, and chair a CKGR Consultative Committee, with representatives from each of six San settlements.

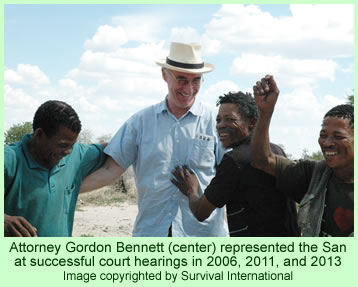

On February 4th, another reporter wrote that the residents of the CKGR are unhappy with the deal, especially about being kept in the dark about what is going on. A group of concerned San has indicated that they intend to contact the British lawyer, Gordon Bennett, who won several notable earlier cases for them in the Botswana courts.

The dissident group is apparently being led by Mogolodi Moeti, a San man who was beaten by Botswana officials in 2014 for supposedly having illegal game meat in his home. When the officials found nothing suspicious, they took him away for the day anyway. Mr. Moeti focused on the fact that the government still refuses to let the San people live on their ancestral lands in the CKGR; he says that what the government is doing is illegal.

The reporter contacted Gordon Bennett who replied that if the government is sincere in wanting to restore services to the San communities, it should give them a binding, written commitment. If it doesn’t, it can simply withdraw its services on a whim, as it has done in the recent past. The lack of a formal guarantee only adds to the insecurity and uncertainty of the people who wish to live in the CKGR.

The reporter contacted Gordon Bennett who replied that if the government is sincere in wanting to restore services to the San communities, it should give them a binding, written commitment. If it doesn’t, it can simply withdraw its services on a whim, as it has done in the recent past. The lack of a formal guarantee only adds to the insecurity and uncertainty of the people who wish to live in the CKGR.

A news source last week reiterated the fact that the San are still suspicious. Despite the suspicions among the CKGR residents, Tshekedi Khama, the Minister of Environment, Wildlife and Tourism, said that his ministry is determined that the San will derive some benefit from tourism in the ancestral lands.

His agency is drilling boreholes to supply water for wildlife and residents, he said, but the government will not withdraw its prohibition on hunting in the CKGR, a ban that was put into effect in 2014. The government does want the San to engage in money-making tourism activities, efforts that will show off their traditional culture—except for the hunting component.

Mr. Khama admitted that the government had not effectively consulted with the San themselves, “because we didn’t want to be seen as if we are imposing things that they don’t want.” Roy Sesana confirmed making an agreement with the government. He feels it provides a long-term solution to the problems of the San.

The Central Kalahari Game Reserve preserves spectacular scenery and wildlife; it used to sustain at least one remarkably nonviolent San society, the G/wi, people who thrived on their hunting and gathering activities on the land. The continued skepticism by many San people that the Botswana government is really reversing itself and will no longer treat them in a brutal fashion may be justified, if past events indicate still-prevailing attitudes.

But despite the well-deserved skepticism, considering past news stories, the compromise does offer good reasons to hope for a better future for the land and the people who cherish it—as well as for those who simply want to make money from tourists.