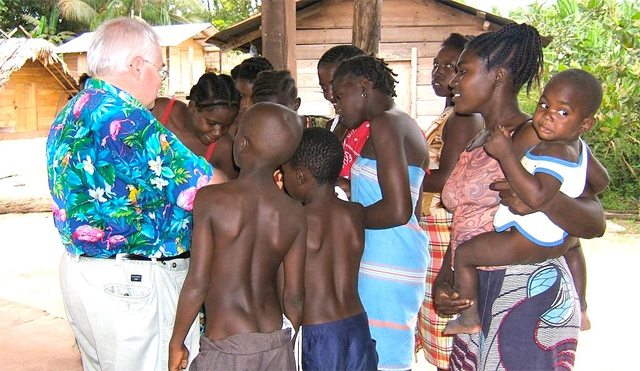

A prominent educator from Massachusetts spent some time on Ifaluk Island 40 years ago so now he has decided to return there to live out the rest of his life. John Chittick was born and raised in the small city of Fitchburg, completed an Ed.D. from Harvard, and went on to have a career as an educator and an advocate for HIV/AIDS education.

As part of his studies at Harvard, Dr. Chittick spent two years, starting in 1975, doing ethnographic filming on various islands in the South Pacific, including Ifaluk and neighboring atolls in the Federated States of Micronesia. He has since traveled to more than 85 countries attempting to promote his message of AIDS prevention. In 2010 he moved the headquarters of his AIDS prevention NGO from Fitchburg to Norfolk, Virginia, and in 2016 he decided to hang it up and move back to Ifaluk. The Sentinel and Enterprise, Fitchburg’s daily newspaper, carried a story about his plans last week.

He made it clear that he does not intend to ever return to the U.S. His goal is to live permanently on Ifaluk—or possibly Lamotrek, another atoll about 120 miles away—and to create a school for their young people, ages 16 through 20. At the present time, according to Sosis (2005), children can get educations through the 8th grade on Ifaluk but they have to go to the nearby islands of Woleai and Ulithi if they want to complete high school. The reason he wants to provide more training for the Ifaluk people is that they may someday have to abandon their island and they will need more advanced skills to survive elsewhere.

His friends on Ifaluk are telling him that when the tide is high and the winds are blowing, sea water is sweeping across the island. Sources of fresh water are becoming brackish and plants are beginning to die as a result. Within 10 to 20 years, he suspects, the islanders will be forced to move to another location on higher ground, like it or not. News stories in this website, such as one in December 2009, have reported on the harm that global climate change is causing on Ifaluk and the other Pacific atolls.

His answer to the dilemma of moving is additional advanced education. Chittick wants to establish an Atoll Academy, a free school in which young adults will write essays and have discussions in English. He plans to establish an Internet connection, powered by a solar electricity system he wants to set up. Given his worldwide connections, he hopes his students will be able to establish good relationships with mentors around the globe. He also expects to help his students prepare applications to colleges and universities in other countries.

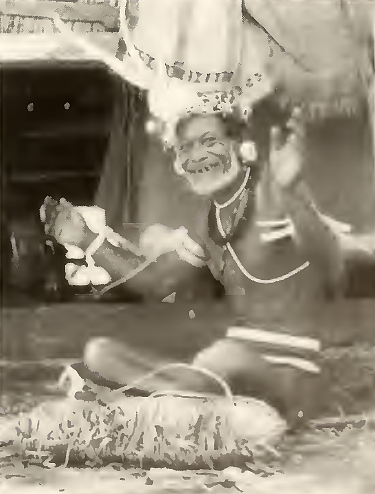

But in addition, he feels it is important for the young people to preserve their culture. To do that, he wants them to use tablets in order to film their ceremonies and traditional events. He expressed pleasure at the memory of the islanders allowing him to film their lives when he visited 40 years ago for his Harvard project. He plans to ship a 950 pound crate of equipment from Virginia to Ifaluk so he can get these projects rolling when he arrives.

He impressed on the reporter the fact that, while he won’t miss having electricity, and wearing the traditional island clothing would be fine, the one thing about Ifaluk culture that he would really like to change someday is their penchant for eating dogs. He’s a dog lover and he hopes he could have a pet again on the island. He recognized that the chiefs on the island would make the final decision on that matter, as they do on most other issues of importance.

The literature about Ifaluk confirms what Dr. Chittick told the newspaper. Bates and Abbott (1958) observed that the Ifaluk sometimes ate dogs. Sosis (2005), who included studies of the food habits of the islanders in his fieldwork, wrote (p.19) that “pigs, chickens, and dogs are also raised for consumption and usually only prepared for bi-monthly feasts.”

A more serious issue is that of preserving the traditional Ifaluk culture when and if the people are forced to leave due to the rising seawaters. Dr. Chittick believes that preservation as possible with the use of modern equipment in the hands of educated young islanders. The anthropological literature implies that the issues may be more complex than that, and that preserving their value systems under changed circumstances will represent a severe challenge if the people do decide to move.

Sosis (2005) wrote that the Ifaluk maintained relatively little contact with the outside world on purpose in order to preserve their traditions. He said that the chiefs actively tried to slow the process of acculturation on the island by prohibiting Western clothing and by insisting that everyone continue to wear their traditional garb. Furthermore, Ifaluk is the sole island in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) on which the residents are not allowed to own motor boats. They must fish from their canoes. “Yap State,” Sosis wrote (p.13), “is unequivocally referred to as the most traditional state in FSM, and Ifaluk the most traditional atoll in Yap State.”

The captain of a yacht that visited Ifaluk in 2012 confirmed the fact that traditions are still essential by writing in his blog that the chiefs on the island appeared to be keeping modern conveniences at bay. Men still did their fishing from traditional canoes, as the chiefs did not permit fiberglass boats and outboard engines. Men and women continued to wear their traditional clothing, he wrote.

And just why is preserving those traditions so important? A work by anthropologist Edwin Burrows (1952) suggested one answer. Writing about the traditional hierarchical order of people on the island, Burrows argued that the practical value of their feelings of rank is the maintenance of law and order. Subordinates defer to superiors and nearly everyone has a sense of pride in their position. This system seemed, to Burrows, to be responsible for the almost complete absence of crime and violence on the atoll. The highly placed chiefs, for their part, virtually never displayed any overbearing conduct or haughtiness.

This prompts the distant observer to wonder what might happen to the Ifaluk traditions and their values of peacefulness if they were indeed forced to move and became exposed to alien concepts that extol the importance of conflict and violence. Lutz (1988) described, for instance, how the Ifaluk reacted with horror to stories of violence and murder in America and the films that depicted such things, some of which they saw on visiting American ships. The people constantly reviewed and talked about the violent scenarios, reinforcing their own sense of their safety from violence.

In another work, Lutz (1985) wrote that the Ifaluk stress moral values in many of their basic concepts. For instance, they do not make a sharp distinction between emotions and thoughts, between the unconscious and the conscious. Their words are quite important in the structure of their morality. A person who leads an exemplary life possesses lots of nunuwan—a word which combines both emotions and thoughts—while social deviants are devoid of it.

Global climate changes will without doubt continue to raise the sea level of the Pacific Ocean in Micronesia, as Dr. Chittick says. It remains to be seen how well the Ifaluk concepts and traditions that help foster their peacefulness will survive if they do have to move away from their delightfully isolated, but unfortunately quite low-lying, atoll.