A month after extreme right racists demonstrated in Charlottesville their hatred for non-white people, another Virginia city proudly celebrated its history of accepting a persecuted African. On Saturday, September 16, the city of Lynchburg, 55 miles to the southwest of Charlottesville, unveiled a public marker to an Mbuti man. Lynchburg congratulated itself for providing sanctuary just over 100 years ago to the individual who had been exhibited in a cage in a New York zoo along with other primates.

The tragic story of Ota Benga, the Mbuti man, was published last month in the local newspaper, the Lynchburg News & Advance, and it was retold with numerous differing details last week in a news post by Liberty University, which is located in the same city. Previously named Mbye Otabenga, Ota Benga was living in an Mbuti band with his wife and two children in the Congo when the group was attacked by the Force Publique, a group of Belgian and Congolese soldiers under the command of the King of Belgium. Most of the Mbuti were killed, including Ota Benga’s family, and he was sold into slavery. In 1902, the South Carolina explorer Samuel Verner traded a piece of cloth and some salt for Benga.

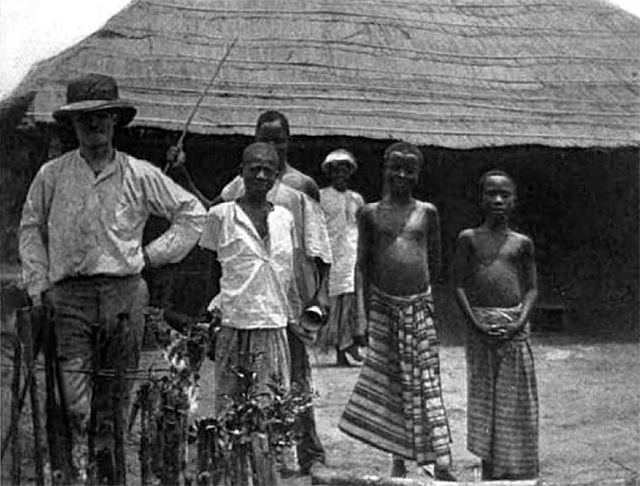

Verner was searching for Africans that would be suitable to be exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair, coming up in 1904. At a height of only 4 feet 10 inches, Benga would be worth the price of admission, Verner presumably figured, a worthwhile purchase. And Ota Benga did become a hit attraction at the fair, reportedly asking for a nickel each time he showed his pointed teeth to the crowds.

After the fair was over, Verner took Benga back to Africa. The two traveled around the continent and Benga tried to readjust to his former life but when his second wife died, he decided to return to America with Verner. Benga started living at the American Museum of Natural History in New York in August 1906 and the next month at the city’s Bronx Zoo.

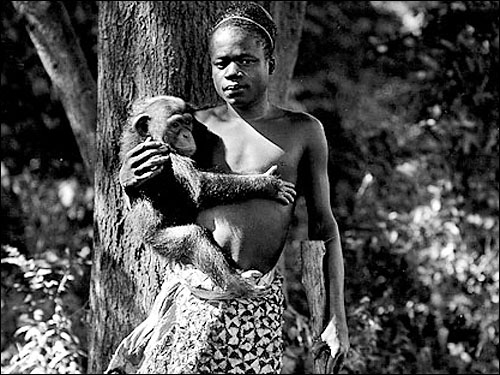

At first he freely roamed around the zoo helping the staff care for the animals but the Director, William T. Hornaday, decided to move him into a vacant cage in the Monkey House where he was encouraged to shoot at targets with a bow and arrows for the crowds on the other side of the bars. The New York Times learned of the latest addition to the primate collection and published a story under the headline “Bushman Shares a Cage with Bronx Park Apes.”

The number of visitors to the zoo skyrocketed and people freely gestured, pointed, gasped, and laughed at the supposed freak of nature who was billed as “The Missing Link” between the apes and mankind. While Benga did not yet comprehend spoken English, he could easily understand that he was the object of scorn and pity. But the African American community in New York, particularly a group of preachers, soon expressed their heated opposition to the display of an African man in a monkey cage. Director Hornaday, who had initially defended his decision to put the Mbuti man on display, relented to the public pressure and released him.

Benga spent the next ten years attempting to adjust to life in America. He moved to Lynchburg in 1910, which provided sanctuary for him until his death in 1916. Ann van de Graaf, Director of Africa House in Lynchburg and one of the speakers at the ceremony in that city on September 16, said that despite the terrible treatment he had gotten in St. Louis and New York, Benga was happy and at peace in her community. He became friends with the African American poet Anne Spencer, who taught him English. He worked at a tobacco factory nearby and enrolled in the Virginia Theological Seminary.

However, he still harbored a desire to return to Africa, but the outbreak of World War I and the impossibility of traveling by sea in wartime thwarted his hopes. He committed suicide on March 20, 1916, in Lynchburg. About 101 years after Benga died, the city unveiled a roadside marker commemorating his life and ensuring that his story would not be forgotten.

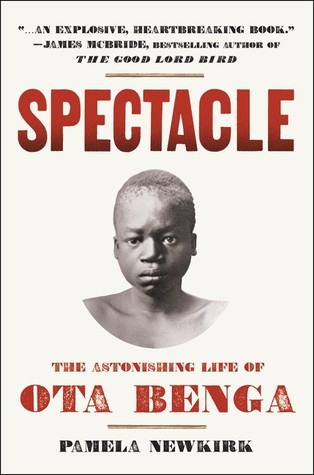

Pamela Newkirk, the author of a biography of Ota Benga and one of the numerous speakers at the ceremony, told the crowd, “… Lynchburg gave this tragically displaced stranger a home and semblance of family, but he also left an indelible mark on Lynchburg. A century later, we are still haunted but also buoyed by his gentle spirit. In honor of him, this marker also reminds us of the handful of New Yorkers who defied the conventions of the day and rose up against powerful men and injustice.” Her words suggest that Benga exemplified the spirit of the Mbuti, as recorded by later anthropologists.

Pamela Newkirk, the author of a biography of Ota Benga and one of the numerous speakers at the ceremony, told the crowd, “… Lynchburg gave this tragically displaced stranger a home and semblance of family, but he also left an indelible mark on Lynchburg. A century later, we are still haunted but also buoyed by his gentle spirit. In honor of him, this marker also reminds us of the handful of New Yorkers who defied the conventions of the day and rose up against powerful men and injustice.” Her words suggest that Benga exemplified the spirit of the Mbuti, as recorded by later anthropologists.

Newkirk went on to say that “… This marker reflects your city’s values and highest ideals. So as you honor a man whose soaring humanity could neither be tarnished nor erased by the inhumanity of others, you illuminate your own.”

The actions of the racists in Charlottesville two months ago, perhaps attempting to reestablish the inhumanity exhibited in New York in 1906, have a long history. The desire to exhibit “Primitives,” people who were thought to be less developed than Whites, was a well-established tradition in European zoos for many years before Hornaday’s time. The Wikipedia has a lengthy, but depressing, article describing the numerous “human zoos,” also referred to as “ethnological expositions,” that flourished long before Mr. Verner brought Mr. Benga from the Congo to be exhibited in St. Louis.

The stories of the peaceful societies are not without their tragedies and instances of violence, of course, but it is hard to come up with anything as overtly inhuman as the history of Ota Benga—and most of the other “human zoos” that used to exhibit people in Europe and America. One can only wonder if the racists who congregated in Charlottesville are proud of that history.