An app is being developed that will allow the Inuit in a remote town to share information about local climate issues on their phones, despite the lack of good internet connections.

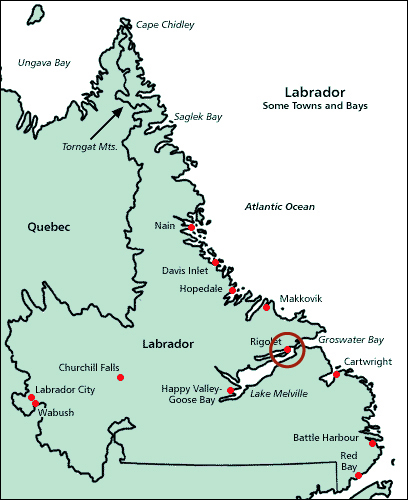

The inhabitants of Rigolet, a small town of 300 people on the Hamilton Inlet near the coast of Labrador, are working with a team of researchers from a couple Canadian universities and a Vancouver business to develop a new app called eNuk, which has begun operating on the network the developers are establishing. According to a news story last week, the problem in the community is that a conventional internet connection via an ISP is simply not possible. The place is too small—300 people—and too remote.

The solution, launched a year ago, is a decentralized internet network, called in technical-speak a “mesh network,” where each device transmits as well as receives. This network technology is being developed by a company from Vancouver called RightMesh, which is cooperating with citizens in the town, local officials, and researchers from the University of Guelph in Ontario and the Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

The basic function of the app is to allow the people to share their videos, images, or text about local environmental conditions, which have been impacted by changes in ocean temperatures. The thick, stable ice that used to allow hunting, fishing, and driving over waterways into other nearby communities during the winter is no longer present. The ice is often thin—sometimes dangerously so. The new app allows people to share vital local conditions easily on their phones.

The role of the company, RightMesh, is to develop what is called blockchain technology into a platform that will allow users to share their internet bandwidth—their connection speed—with one another, but for a charge. And that sharing is accomplished without any centralized authority monitoring the transactions. The company is developing the technical aspects of the project while the researchers and the community are providing the feedback. RightMesh argues that unless there is an incentive—money—residents will not continue to share their bandwidth and the network will be short-lived.

The news article quoted Jason Ernst, a scientist at RightMesh as saying, “If you have your cell phone plan, you’re not going to just volunteer your data to somebody else for free.” There was no mention of the Inuit tradition of sharing in the article, and it was not clear from the story if the developers on the other side of Canada had considered it. In any case, when users in Rigolet want to watch a YouTube video, or anything other than the local climate change app, they will be able to do so, but at a small charge in tokens that will go to those who prefer to spend time out on the land or who want to use the internet later.

The journalist writing the article contacted Charlie Flowers, a resident of Rigolet and a research associate employed by RightMesh, about the developing project. He replied that “any mention of improved internet connectivity in a town with no cellphone service and sub-par internet speeds is an exciting and welcome bit of news.” Ernst believes that, although the town is remote, the houses are densely clustered together so the network will only require about 50 smartphones in order for the platform to work properly.

The developers are considering the ways people may want to use the system. If they decide to take photos of holes in an ice road at some remote location, their phones will save the messages and automatically send them to others in the community as soon as the phone returns to the town and the range of its mesh network. The hope is that eNuk will not only allow people to track physical changes in the environment but to also, potentially, save lives.

Mr. Flowers expanded on his enthusiasm for the developing possibilities of eNuk. He explained that it may also be developed to help preserve Inuit traditional knowledge. Younger people who are comfortable using the smartphone technology may be persuaded to film their elders utilizing the resources they obtain from the land. For instance, making a poultice out of juniper, a traditional healing technique, could be filmed and shared on eNuk so it would be preserved for coming generations.

The Inuit people of Rigolet appear to be excited by the possibilities for preserving and sharing knowledge with this new technology. It will not only help preserve traditional ways of doing things, it may also, as it is developed, assist with the functions of the local government. Officials and researchers are hopeful that the new approaches to smartphone technology may provide a model for other remote communities in Canada’s north so they can better attain their goals as well.