The well-known Zapotec rug weaver Pastora Gutierrez Reyes made the news again last week, this time in a New York Times feature. Ms. Gutierrez, a leader for women’s rights in the town of Teotitlán del Valle, in Mexico’s Oaxaca State, was described in Lynn Stephen’s book Zapotec Women (2005) and more recently in a Truthout story.

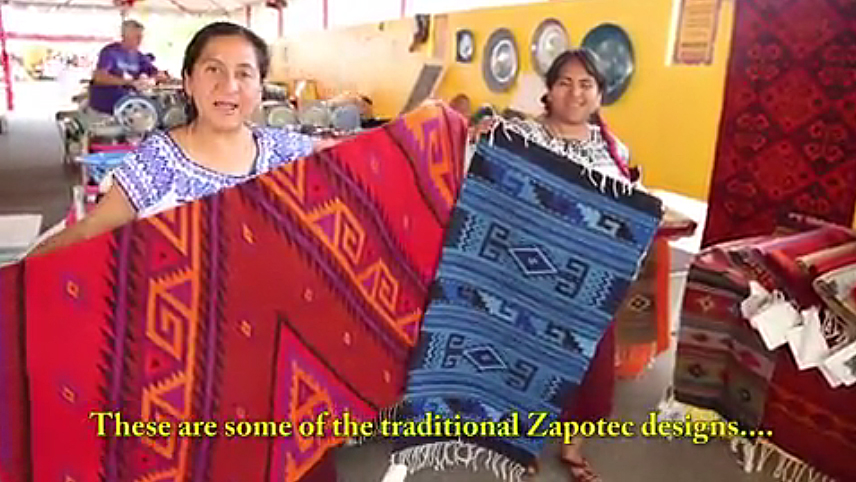

The Times reporter, Deborah Needleman, relates how Ms. Gutierrez welcomed her into her home while she was making red dye out of pulverized cochineal, an insect. The 46-year-old weaver tells her that the recipes she uses for her dyes all came from her great-grandmother. She weaves colorful rugs with patterns that capture the traditions of Zapotec life and the surrounding natural world.

Gutierrez then provides the reporter with some of her background. About 20 years ago, she and the other women of Teotitlán were being exploited by middlemen in the village of about 5,500 people. Many of the men in Teotitlán, located about 12 miles east of the city of Oaxaca, had left for the United States for work and the middlemen were exploiting the women and cheating them out of their earnings from the rugs they made. They were paying the women less than their costs.

Led by Gutierrez and some others, the women tried making other craft products than rugs to sell but the middlemen insisted they had to continue making just rugs for them. So the women started working for the middlemen for a week, then for themselves the next. In response, the men tried visiting the women in their homes at night.

Gutierrez heard about a government scheme that would grant funds to rural Mexican women so she decided to apply. She had not realized the corruption involved—grantees had to attend political rallies for the ruling party. In any case, they got the grant, which allowed them to purchase wool, fabricate rugs, and sell them from their homes. But the middlemen continued to threaten them so they started traveling every week to Mexico City markets, over 200 miles away, in order to avoid undercutting their adversaries.

Their journeys to the capital city caused them to be ostracized in Teotitlán. To make matters worse, they discovered that the grant had in fact been a loan which they were unable to repay. They were shunned in their own village until they sold their livestock and jewelry and were able to repay the loan. And to make matters worse, they still were required to attend the political rallies.

But a woman named Flor Cervantes, who worked for a nonprofit organization, came into the village about 10 years ago and brought new ways of looking at things. A younger sister, Silvia Gutierrez Reyes, interrupts the story to show Ms. Needleman some old family photos. It becomes clear from the conversation among the three women that until the visits with Ms. Cervantes had started, even the facts of a woman’s reproductive organs were unknown to the ladies of Teotitlán.

Cervantes worked to slowly build the self-esteem, knowledge and confidence of the Teotitlán women, who also gained a lot of information from her about domestic violence. The reporter writes that she had a hard time reconciling the confident leader of the women in today’s Teotitlán with the stories by the same individual who was feeling completely powerless just 10 years ago.

Vida Nueva, the cooperative that Ms. Gutierrez founded, has between 13 and 20 women members. Once it received official approval, it was able to sell products outside Mexico. The members of the cooperative initiate different programs every year, each woman donating profits of her own choosing for the efforts. At one point, the U.N. granted them the funds to purchase new looms.

With all the obvious successes and profits from their creative work, the reporter asks how the men in Teotitlán treat her now. Ms. Gutierrez replies that the men today are showing respect for her. And she says there is less machismo in the village, at least toward herself. Vida Nueva spearheaded a recycling system for the village, founded an eldercare program, and initiated a project to reforest communal lands. And last year she became the first woman to take a position in the village assembly, so things are changing slowly.

“Just a year before,” she told the Times, “no one wanted a woman to have a position.” The men respect the way she has varied the offerings of the cooperative—they diversified from just rugs to also making pillow cases, totes, and bags. The reporter indicates that the improvements the women have brought to Teotitlán have been based on their ethic of welcoming changes only when the entire community benefits, a basic value of the Zapotec.