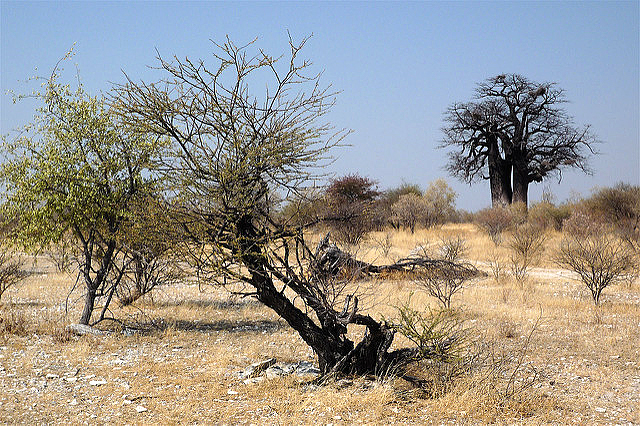

The Ju/’hoansi are working with land managers to protect the surrounding Kalahari Desert lands from hot-season fires that threaten their villages and their livelihoods. A news story in the online newspaper Namibia Economist last week reported that seasonal fires, especially in the summer in southern Africa, pose a serious environmental threat. The Ju/’hoansi have been starting controlled burns for a long time and they are now benefiting from the research and advice of land managers in protecting the Kalahari. The news story updates a similar report from two years ago, though it emphasizes somewhat different points.

According to an overview of a 10-year study by the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation (NNDF) of fire in the desert region, 50 percent of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy lands had burned in 2010 and the extent of burned lands was increasing. The NNDF report argued that if that trend were not checked and reversed, the fires “would seriously impact and threaten the survival of the community as well as fauna and flora in the area.”

The NNDF said that land managers, working with the Ju/’hoan villages, decided in 2013 to take a more proactive approach. They increased surveillance of fires and introduced the management of fuel by selectively doing prescribed burns. While the villagers themselves welcomed the proposed management approaches, some people, whom the article did not name, did not. Those opponents advocated more traditional fire-fighting techniques such as fire breaks and firefighting. The foundation argued that in a wild area of 9,000 km2, those approaches are mostly ineffective.

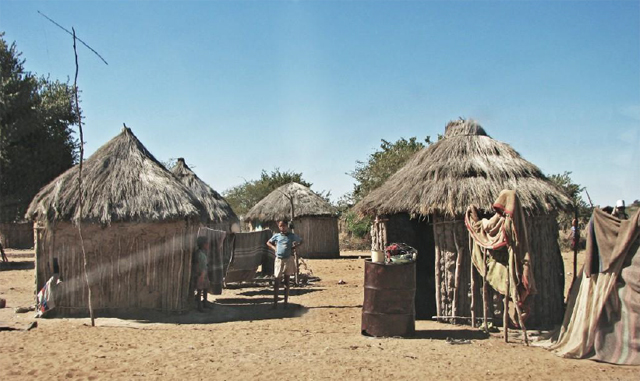

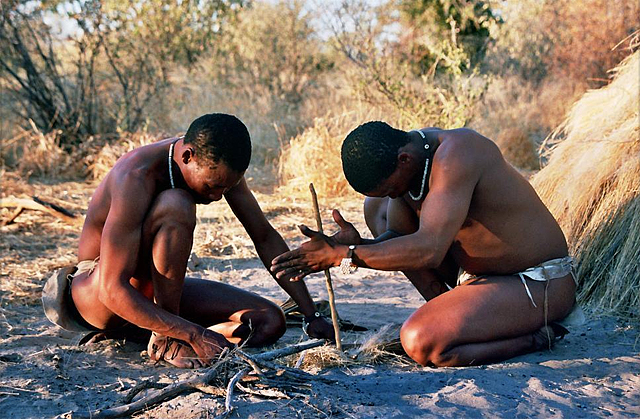

The Ju/’hoansi San accepted the seriousness of the situation and agreed with the prescribed burns, particularly since the burns were proposed for the vicinity of their villages in order to protect their communities and for areas where they utilize natural resources. The land managers developed their proposals to match up as much as possible with traditional fire burning practices, for the Ju/’hoansi had been setting controlled burns for a long time.

The strategy of the communities, assisted by the researchers, was to use remote sensing fire maps and a Normalized Difference Vegetation Index in order to locate areas where highly combustible vegetation, such as brush and dry grasses, had built up enough to pose a serious risk of fire. Then those areas would be selectively burned well before the hot season, September through November, began.

The communities and the researchers working with them soon realized that when an area had been burned, more burning the following year would probably be unnecessary. Standardized annual fire-burning plans had to be continually modified to meet the actual conditions on the ground. Fire plans had to be prepared each year based on surveillance of existing fuel loads. The 2017 burn map showed only a limited number of spots containing high or very high build-ups of fuel. Prescribed fires were restricted to only those spots. Conditions were worse during 2018. The burn map showed a lot more spots with heavy loads of dry fuel, so more prescribed fires were started.

Over the course of the past decade, the Ju/’hoansi have changed their approaches to fire management. During the first half of the project, from 2009 – 2013, the researchers and managers from NNDF were in a monitoring phase with the villagers. The people still held onto their traditional beliefs about fires, which destroyed about 40 percent of their resources each year. In the second half of the decade, 2014 – 2018, that figure has dropped to about 16 percent of their desert burning each year. In addition, the timing of the human-set fires has changed. Traditionally they were set during the hot season, September to November. They have shifted the prescribed burns to mid-season, June to August.

The article last week in Namibia Economist unfortunately opens with a couple pejorative paragraphs about the Ju/’hoansi and their fire burning traditions, observations that differ from the news story of February 2017. The reporter last week wrote that the tradition of the people setting their desert into flames was based on superstitions about their rain gods and it was very difficult to convince the local Ju/’hoansi to question those traditions.

The 2017 article, also based mostly on reporting that year by the NNDF, “indicated that this new management approach fits in well with the Ju/’hoansi cultural tradition of selectively burning the desert lands during May through July, the cooler months in southern Africa.” That 2017 piece referred to an article by Hitchcock et al. (1996) that pointed out how the Ju/’hoansi have traditionally used controlled burns in order to manage the resources they take from the desert. The unnamed reporter writing for Namibia Economist does not indicate the sources for the curious statements about the people being hesitant to question their superstitions.