Back in early April, reports came out about a mysterious illness that was afflicting the Batek of Kuala Koh: some young people were becoming sick and having breathing problems. The state health authorities in Kelantan attempted to provide cover for themselves by blaming the Batek for not being willing to take transportation to clinics to get tested. The cause of the illnesses remained a mystery. A couple weeks later, however, despite some recriminations, the people in the village seemed to be getting better.

On June 10 the story became a national scandal when it was revealed that over the course of the previous month two Batek people had died of pneumonia and 12 other bodies of individuals who had also died of the mysterious illness were going to be tested. Scores of news reports were published in Malaysia and at least one international source—The Guardian—picked up the story. The reports quoted numerous state and national officials, including the Prime Minister, scholars, and some Batek individuals.

Some Batek suspect that they are dying because of contamination of their water supplies due to mining near the community. Inja Punai, a 32-year-old resident of Kuala Koh, was quoted as saying “we have not made accusations but suspect that the water pollution is caused by chemical waste.” An NGO, Sahabat Jariah, indicated that nearby explosions and thee uses of chemicals have been polluting the area.

The NGO added that the river water around the village had been sampled by staff from the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, who found it to be contaminated with arsenic, metals, and chemicals from fertilizers. “The blasting ingredients are said to be processed near the water source of the village” Sahabat Jariah posted on its Facebook page.

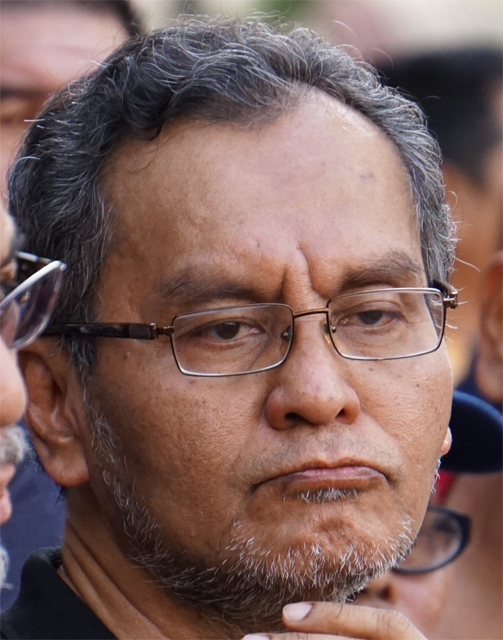

The national health minister, Dzulkefly Ahmad, spoke about the situation at a press conference held in the Gua Musang hospital. He admitted that environmental poisoning might be a cause of the crisis. Lung disease could be caused by the mining being done at a manganese mine in the area. The Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, responded that the government would take “stern action” if indeed it turned out that the Batek had been poisoned.

Another news source reported that Senator Datuk Husan Musa of Kelantan wants the state government to carefully investigate the issue of iron ore mining close to Kuala Koh to see if it is linked to the deaths in the community. He wanted to know if the iron mine was operating without a license. He said that a state official who had recently visited the village had understood that the mine was operating illegally. During his visit on June 9, he learned from the supervisor of the mine that they had been using explosives in the operation, though it was not clear what type.

The senator pointed out that two rivers may have been responsible for carrying pollution to the village. The Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources said that they would investigate the possibility that the deaths due to pneumonia might have been caused by water pollution.

A different news story reported that those claims are impossible to substantiate—the Health Ministry said, according to this source, that chemicals could not have caused the deaths of the Batek. The reporter quoted Dzulkefly Ahmad as saying that chest X-rays of the victims of the illness showed that they were caused by microorganisms, not chemicals. He added that he was awaiting the results of the polymer chain reaction tests to determine if the disease is viral or bacterial.

Due to the possibility of a serious, infectious pathogen, the government has decided to exclude all outsiders from the community. As of noon on June 11, Dzulkefly Ahmad said that there have been 101 recorded cases of the disease, at least 14 of which resulted in the deaths of the victims.

While the villagers may blame pollution from an illegal mine and medical authorities may be on the verge of finding a disease pathogen, others are blaming the crisis on the rampant logging of the forests around the Kelantan community and, by extension, on the lack of land security for the Batek. Colin Nicholas, Executive Director of the Centre for Orang Asli Concerns, said that the basic problem was not a medical one but rather it was the fundamental disregard for the land rights of the Batek and the other Orang Asli people.

He stated his argument eloquently. The Batek of Kuala Koh were hunters and gatherers and 10 years ago they were mostly contented and healthy. But the state government of Kelantan has been steadily taking away their lands and traditional resources, forcing them into constricted settlements.

“Without access to their traditional way of life, they become malnourished and underweight,” Nicholas said. “They end up eating junk food and consuming more sugar to substitute their diet of fruits and other things. With their resistance being low, many diseases — whether it’s pneumonia or tuberculosis, or even diarrhea — can be fatal. But the root cause is that their environment has been taken away,” he said. His most recent visit to Kuala Koh was about a year ago.

The crisis in Kuala Koh has served to focus the Malaysian media on the Batek, and the Orang Asli more broadly. One of the news stories published on June 10 consisted of an interview with associate professor Dr Wan Ahmad Amir Zal Wan Ismail from the Universiti Malaysia Kelantan about the expertise of the Batek in the forest. He explained that they are still uniquely capable of thriving in the forests that surround their communities.

While they no longer live full-time in the forest, they normally will enter it accompanied by family members and live in a tent for a few days or for longer periods of a month or more. Depending on the availability of forest resources, they may stay in one spot or move to different locations. They will erect temporary shelters in the forest during the monsoon season, October through December or January.

He said that the Batek, who still hunt with blowpipes, were quite knowledgeable about the wildlife around them—birds, squirrels, monkeys, and other animals. “Their value of total reliance on the jungle renders them invulnerable to the pressures of normal and routine needs as they believe that the jungle will provide without fail,” he observed.

The scholar said that while they are camped in the forest, the Batek men will forage for honey, frogs, resin, agarwood, bamboo and rattan, among other resources. Meanwhile, back in their tents, the Batek women will care for the children and forage for forest herbs and foods. Compared to other Orang Asli groups, the Batek are justifiably known for their intimacy with the Malaysian forests.

On Monday, June 17, the mystery about the illness was finally solved. Dr. Dzulkefly Ahmad announced that 37 of the sick people in Kuala Koh had tested positive for measles. They had not been vaccinated.