It is not too soon to begin celebrating the centenary of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees American women the right to vote. Already, our news media are reporting on local celebrations of the growing gender equality in the U.S. that the amendment symbolized, which will presumably culminate on the actual anniversary of the amendment, August 26, 1920. But the celebrations of the right to vote can’t mask the fact of hidden, and not so hidden, discrimination that persists against women in this country and in the other nations of the world that also guarantee women the right to vote.

It might be tempting to explore the issue of gender equality in the peaceful societies, but such a task would be beyond the scope of one news report. Besides, the fact is on this particular issue, the societies differ widely from one another. While they typically accord a high measure of respect to women, and there is little actual violence against them, equality is a different story. Except in one society—the Batek.

The Batek have a highly egalitarian society. Unlike many hunter/gatherer societies, which accord more value to men’s hunting than to women’s gathering, while the Batek men normally hunt and the women usually gather the vegetables, both foods are valued equally. Both sexes are part of the sharing network of foods in their camps. In essence, men sometimes gather vegetables and women sometimes (though rarely) hunt—they have no rigid rules separating their gender roles. Both sexes gather the rattan which they trade for outside goods, and men and women both participate in government-sponsored agricultural activities.

Marriages are based on equality, compatibility, and affection; couples make joint decisions about movements and food-getting. They live companionable lives, working together and enjoying their leisure time with one another. If the warmth of the relationship erodes, either can divorce the other and count on the support of the band to assist with child-support and food-sharing (Endicott, Karen Lampell, 1984).

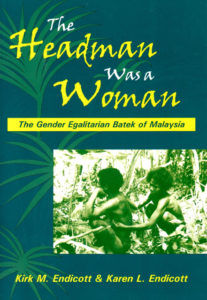

Kirk M. Endicott and Karen L. Endicott define gender equal societies as ones where neither sex controls the other or has greater prestige. By this definition, the Batek enjoy one of the few gender equal societies on earth—at least they did in 1975 when the Endicotts did most of their fieldwork among them.

When they arrived at the Batek settlement, the anthropologists discovered (Endicott, Kirk M. and Karen L. Endicott, 2008) that the people did not follow the patterns of other hunting and gathering societies, with only the men doing the hunting and women doing the gathering. Batek society was different. The men and women sometimes worked together on hunting or gathering tasks, at other times each sex separately hunted or gathered, and frequently they assisted each other with childcare.

The “headman” of the band was a woman named Tanyogn, a born leader of her community. A middle-aged, energetic individual, at times she had to strenuously advocate for her people by confronting outsiders. For instance, one day outside traders tried to blame the Batek because some cut rattan had floated away on a flood. She shouted at them that they were the fools who had piled the harvest on the bank of the river. The Batek, she said, would have had the common sense to pile products like that safely in the forest.

The “headman” of the band was a woman named Tanyogn, a born leader of her community. A middle-aged, energetic individual, at times she had to strenuously advocate for her people by confronting outsiders. For instance, one day outside traders tried to blame the Batek because some cut rattan had floated away on a flood. She shouted at them that they were the fools who had piled the harvest on the bank of the river. The Batek, she said, would have had the common sense to pile products like that safely in the forest.

Another time, some Malays took corn from a Batek garden. The head lady confronted them and demanded that they pay the victims two jugs of rice or she would report them to the government. They paid.

Tanyogn was constantly involved in the affairs of the community and she led by example, pitching in to work with others on many projects. She got the two anthropologists involved by having them weigh produce for them, in order to help keep outside traders honest. She was a hands-on leader, a strong personality, and an expert on many subjects. The Batek were under no obligation to follow her recommendations but they normally did.

The Endicotts did notice that the Batek recognize physiological differences between the sexes in addition to the obvious reproductive functions. Men have a stronger breath than women, they believe, which explains why they can use blowpipes more effectively to hit monkeys higher in the trees than women can. They also think that men have greater strength for climbing tall trees, though young women also climb reasonably well.

Among the Batek, the nuclear family is formed by a willing agreement between a man and woman to live together. After they are married, the couple make all decisions jointly, though one or the other may be the more vocal. Either can simply walk away from the marriage at any time. The Batek do not always favor meat, the normal result of men’s efforts, as the preferred food. During the season when fruit is plentiful, they will eat it instead of everything else, including meat. Karen Endicott concluded that the domination of men over women in many societies is based on established authority structures; that male domination is not universal, hunting is not necessarily a pre-eminent role, and meat is not necessarily the most highly prized food.

However, after a number of years of exposure to the outside world, gender relationships appear to have been affected in some Batek communities, as a few news stories over the past 15 years have described. The status of women may be starting to fray in some communities due to outside influences. Patrick Mills, the author of a scholarly report published in 2015, observed that recent developments such as the employment of Batek men may be threatening their traditions.

Mills provides careful background in his report. He writes that the Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (MyCAT), organized in 2003 as an association of several Malaysian conservation organizations, recognizes that the Batek possess a special knowledge of the forest and of wildlife patterns in them, particularly the habits of the threatened tigers. The group began employing the Batek in tourism activities. MyCAT started what it called “Weekend CAT walks” (“CAT” stands for Citizens Action for Tigers) in the region between the Taman Negara National Park and the central forest reserve. Volunteer tourists hike through forested areas along with experts, documenting such signs of tiger activity as nests and pug marks—as well as poaching activities, which the teams carefully dismantle when they see them. MyCAT includes the Batek as guides for these expeditions.

A Malaysian social organization, Ecoteer, became the organizer of these weekend projects. It employs the Batek as guides in the Weekend CAT Walks. Mr. Mills, who is the Volunteer Coordinator of the project for Ecoteer, focused his report specifically on the Batek community of Batu Jalang, located on the western border of the national park. Mills made many observations about the Batek based on his experiences and his research, but his comments about their knowledge and connections to the forest and the possible deterioration of their gender relationships may be of most interest to those concerned with their peacefulness.

The author pointed out that the Batek near the national park have become more and more dependent on farming and wage labor, which help separate them from their connections to the forest and threaten their traditional social structure. Furthermore, most of the jobs have been reserved for men, prompting them to become the primary wage earners in their families, much like the surrounding majority Malay society. As a result, Batek women in that community have become dependent on men and have taken on more subservient roles in their families.

In a parallel development, Daniel Quilter, the founder of Ecoteer, recognized that the forest knowledge of the Batek made them ideal for conservation work which would help protect the tigers, such as tracking, establishing camera traps, and collecting data. “They have the basic skills to do everything themselves,” Quilter explained. If the Batek had “a bit more focus on things like how to use the GPS and data recording, then we could really start building a good map of animal movements.” Mills wrote that further training for the Batek would allow them to gather data such as seasonal changes of tiger populations that would then suggest better conservation strategies.

Employment in these kinds of forest-based activities would not only be helpful for the conservation goals of the organizations, it would also foster an alternative to wage labor and farming. But the critical issue became the fact that the guiding jobs were only being taken by men, even though Batek women have an equal knowledge of the forest. In order to address this issue, MyCAT and Ecoteer introduced activities that involve Batek women with the volunteer tourists, including leading camping trips and foraging. As a result, the volunteer tourists are gaining a richer knowledge of Batek society, while the Batek are more equally earning income and sharing their knowledge of both their hunting and their gathering. As of the 2015 date of the report, the effort was still rather small, with only a handful of male guides for the CAT walks and a group of 6 to 8 women who were leading foraging trips and camping.

Mr. Quilter held a meeting in August 2015 with members of the Batek village in an effort to explore concerns about the program. The Batek welcomed the new forms of employment but some of their elders were concerned about the numbers of outsiders who might come into their village. Too many visitors might lead the Batek to reveal too much of their traditional knowledge. For his part, Mr. Quilter described his concerns about the lack of sharing among the Batek families of the different opportunities that were being offered to them. The meeting concluded that no more than 10 outsiders per day should be permitted to visit the community, and that the Batek should introduce a rotation system among themselves to better share the benefits of the employment.

The point of all this is hope. If the evidence suggests that even a traditionally gender-equal society can face the stresses of an outside, male-dominated world and reassert its traditional values, dare we hope that women in that world can also overcome continuing discrimination and build a culture of peacefulness based on gender equality? Dare we hope?