The fame of Alexandria, Egypt’s second largest city, with over 4 million inhabitants, is based in part on its incredible history, its wonderful modern library, and its ancient tradition of multiculturalism. A cosmopolitan cultural center right from its founding in 331 BC by Alexander the Great, the city became home to sizable populations of Jews, Coptic Christians, Greeks, and others.

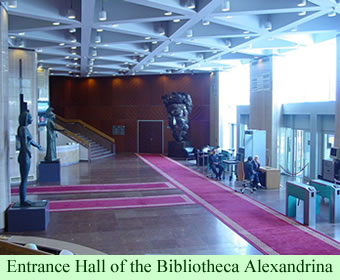

The great library of Alexandria was one of the intellectual treasures of the ancient world until it was burned by intolerant conquerors. The importance of the city was symbolically reaffirmed with the dedication, in 2002, of the new, high-tech, Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a modern recreation of the famed ancient center of world learning.

The great library of Alexandria was one of the intellectual treasures of the ancient world until it was burned by intolerant conquerors. The importance of the city was symbolically reaffirmed with the dedication, in 2002, of the new, high-tech, Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a modern recreation of the famed ancient center of world learning.

The vitality of the city’s diverse ethnic communities began being augmented over 100 years ago by Nubian families who started moving to northern Egypt. Men who needed work, and were not satisfied with farming in Old Nubia, in southern Egypt, moved to Cairo and Alexandria, returning, perhaps sporadically, to their villages for brief visits.

With much of the world’s attention focused on Tahrir Square in Cairo recently, NPR decided last week to send correspondent Corey Flintoff to visit Alexandria, to capture the mood in that city, particularly among its famous minority communities. How would they be affected by the momentous changes occurring in their country?

Flintoff points out in his report that the historic toleration for the city’s minorities started to diminish during the nation’s successive military dictatorships beginning with President Nasser in the 1950s. Historian Mohamed Awad told NPR that the long tradition of multiculturalism, which had persisted for the most part throughout the Roman and the Islamic periods, has dwindled in recent decades. The horrific car bombing of an old Coptic church in the city, killing more than 20 people this last New Year’s Eve, highlighted this downturn.

But according to the NPR reporter, the minority peoples that remain, particularly the Coptic Christians and the Nubians, are hopeful that things will now be getting better. Alaa Setyan, a lawyer who works for human rights, expresses his hope that the Christians and the members of the Muslim Brotherhood in the city will fare better. He looks forward to a lessened workload.

Flintoff interviewed famed Egyptian novelist Haggag Hassan Oddoul, a writer born in Alexandria of Nubian parents who is well known both for his fiction about his people and for his outspoken advocacy of their rights. Oddoul was not overly optimistic about the future of the Nubians when he met the reporter in a cafe: “We are sad because the world, they don’t know about our case, they don’t know. We ask all the people of the world, look at us. We are in trouble,” he told him.

Oddoul told NPR that the Nubians were displaced from their lands in southern Egypt when the Aswan Dam was built in the 1960s, and they are now a marginalized people, scattered across the country. He did express hope that the revolution would encourage the Nubians to advocate their cause to the rest of the Egyptian people.

The NPR story closed by mentioning Mr. Awad again. The historian hoped that the spirit of cooperation he witnessed among Alexandria’s minority groups during the revolution would translate into a better future. He anticipated that one of the many benefits of the revolution would be that it will afford the city the chance to regain its intellectual, cosmopolitan status. Although Mr. Flintoff does not say so directly, one can infer from his report that Mr. Oddoul was far more guarded in expressing optimism about the Nubians.