It may be hard for non-Amish Pennsylvanians to appreciate the fact that their peaceful, hard-working Amish neighbors may have other things to do than spend money on consumer goods.

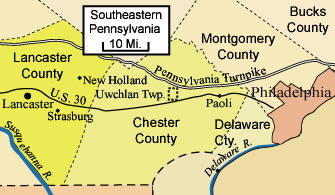

The Amish disinterest in consumer spending, combined with their habit of working hard, may be starting to sour some attitudes toward them in the Philadelphia suburbs west of the city. Some roofing companies along the Mainline feel they simply cannot compete with Amish contractors coming from Lancaster County and the western fringes of Chester County who make significantly lower bids on jobs.

The difference: the Mainline contractors blame the social security taxes, which the Amish do not have to pay, as a major reason why they can undercut their bids. The arguments are similar to the ones made by jealous manufacturing firms in Canada that have a hard time competing with Hutterite enterprises, which sell their products for less.

The reporter for a Philadelphia Inquirer story last week, Harold Brubaker, quotes Keith McLean, a roofing contractor from Paoli, who owns Hancock Building Associates, Inc. He lost a job recently when his bid of $8,000 turned out to be more than $3,000 above a bid from an Amish competitor. He told the Inquirer that his “wiggle room,” the amount that he could bring down his bid, is in the hundreds, not the thousands of dollars. “I don’t have three grand” to bargain over, he said.

The reporter for a Philadelphia Inquirer story last week, Harold Brubaker, quotes Keith McLean, a roofing contractor from Paoli, who owns Hancock Building Associates, Inc. He lost a job recently when his bid of $8,000 turned out to be more than $3,000 above a bid from an Amish competitor. He told the Inquirer that his “wiggle room,” the amount that he could bring down his bid, is in the hundreds, not the thousands of dollars. “I don’t have three grand” to bargain over, he said.

Since their Amish competitors do not have to pay social security taxes for their Amish employees, they have an unfair advantage, Mr. McLean argued. Also, as with the Canadian Hutterites, the American Amish are allowed a religious exemption so they are not required to pay workers’ compensation insurance. “If they are going to come into our community, they need to conduct their business the same way we do,” the contractor told the newspaper.

The Amish contractors, needless to say, see their competition differently. John F. Stoltzfus, owner of Countryside Roofing & Exteriors in Strasburg, said that one of their major advantages over the Mainline firms is that they come from somewhat less expensive areas farther out in the country. Their costs are not as high.

Amish contractors have been doing business in the Philadelphia suburbs for many years, but before the economy dropped three years ago, the mainstream, “English,” contractors also got plenty of customers so they didn’t complain. Now they do. One complaint is that the Amish go back to their homes without even spending their money in the suburbs.

Steve Kraegel, owner of CedarTek, a roofing firm in Paoli, called the phenomenon of Amish coming in from the country and taking jobs a form of “outsourcing.” The Inquirer noted, however, that when suburban homeowners pay less money to get work done, they then have that much more to spend, so it would be hard to calculate whether the influence of the Amish businesses is a positive or a negative influence on the economy of the Mainline.

Mr. Brubaker interviewed Aaron S. Esh, President of Esh Home Improvement in New Holland, an Amish firm, about the situation. His attitude is that his employees simply work faster and harder than the people hired by his competitors. He was not modest in discussing his company. “The faster my guys work, the lower I can bid. If my guys are efficient and they get the job done in half the time, guess what? I’m going to bid lower.”

Mr. McLean dismissed that reasoning when he was told of it. It’s not true that they work faster, he argued, but he admitted that the Amish do have fewer expenses than their “English” competitors. For instance, they don’t have high bills for cable service. He was refreshingly candid. “They don’t have a lifestyle. They just work.”

The news story mentioned the familiar—that the Amish do not have to participate in the Social Security system—but it also indicated that Pennsylvania law, along with some other states, permits businesses to exempt Amish employees from participating in Workers’ Compensation due to religious reasons. Typically, Amish firms that do not want to participate will be set up as partnerships, with each worker being a part owner.

But six of the ten Amish contractors the reporter interviewed do, in fact, pay for the workers’ compensation insurance. The reporter found that that insurance, at least in Chester County, was not a factor in the competitive difference between the Amish contractors and the non-Amish ones.

The reporter examined the records of suburban Uwchlan Township in north central Chester County to compare the applications for permits to contractors. Out of 125 permits issued for replacement of residential roofs, about one-fifth went to Amish firms. Slightly over half of them had workers’ compensation insurance.

Two different homeowners, interviewed by the paper about the jobs that had been done on their homes, were enthusiastic. Clifford Hoffman indicated he had hired L&S Construction from New Holland. Their bid, of $1,800, was less than he had paid ten years before for a new roof. He did not bother to get a second bid. “They did an excellent job,” he said of L&S. “Everything was perfect.”

George Marion hired Beiler Bros., also of New Holland. Jenna Marion said that George had hired them, not because their price was significantly less, but because he thought that they would do a quality job. Mr. Brubaker tries to retain his journalistic objectivity in his news story, but it is apparent that the arguments of the English contractors are not as convincing as the evidence about the work ethic, and lack of consumption, by the Amish themselves.