Chewong elders are often dismayed when animals that are killed in the forest are not shared in the village, a result of the economic and social changes occurring in their society. Signe Howell describes those changes, and the ways the Chewong are coping, in a recently published article.

Starting in 1977, Howell spent 18 months doing field work among the Chewong, a relatively isolated and highly peaceful Orang Asli hunting and gathering society in Peninsular Malaysia. She has returned to visit them in 1981, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2006, 2008, and 2010.

Starting in 1977, Howell spent 18 months doing field work among the Chewong, a relatively isolated and highly peaceful Orang Asli hunting and gathering society in Peninsular Malaysia. She has returned to visit them in 1981, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2006, 2008, and 2010.

In her latest piece on that society, she describes not only the ways they have been changing over the past 33 years, she also analyses her own evolving relationships with the people. She compares her involvement with the Chewong with her fieldwork among the Lio of Flores Island in eastern Indonesia, whom she has also visited repeatedly. Her analysis of the changes in Chewong society, and the persistence of their core cultural values, is of considerable importance to any study of their peacefulness.

Howell notes that logging, new forest roads, and Malaysian government pressures on the Orang Asli (aboriginal peoples) to settle into permanent villages began not long after her initial period of fieldwork. Those outside forces introduced a money economy into their culture, especially cash incentives for harvesting forest products that would be sold to traders who had consumer goods for sale. Such economic incentives quickly produced changes in their social structures.

An elephant sanctuary, established next to their village in 1986, brought tourists to their community at the edge of the forest. Howell felt that she, herself, was becoming, on each visit, as much an historian recording upheavals in their society as an anthropologist attempting to understand their culture.

In this article, she identifies two core values which seemed to be essential in Chewong society 30 years ago, yet which, though muted today, still appear to have considerable importance. The two values she identifies are, first, a strong belief in equality and, second, a moral opposition to what they refer to as punén. The Chewong still cherish both values, though in modified form.

She describes punén as the Chewong abhorrence for eating alone, for not sharing available food. It is a highly condemned, supremely anti-social act. All foods killed or gathered, according to punén rules, are carefully shared. Sharing is—or used to be—a foundational value for people living in a foraging economy. To not share properly might lead to condemnation by everyone, as well as attacks by the spirits.

But the careful rules that prescribed how, when, and what to share have been eroding due to the availability of money and the tendency of people to purchase foods with their own earnings. People still invoke the punén rules, but more selectively now. Foods and other products bought in shops belong to the individuals who purchased them. This contemporary process, of not sharing widely, still makes the people uncomfortable.

Hunters continue to kill game in the forest, and they will still share meat with close family members in the gateway village. But they often will not publicly display the carcasses as they used to, and they may try to withhold information from others about their hunting successes.

However, when game killed in the rainforest is consumed in forest settlements, it will still be shared according to traditional rules. But even while people are living in those forest settlements, the men are also spending time collecting minor forest products for sale. The goods subsequently bought at the store will be retained for family use and not shared.

These changes are fracturing their earlier commitments to equality. Men are earning more money than women, so they are becoming the decision-makers for their families. They also spend excess money on the goods that they want for themselves—televisions, clothing, motorbikes, and such.

The outsiders, the store owners and traders, of course notice the men who are the more successful wage earners and give them increased attention, thus creating additional inequalities in Chewong society. However, counterbalancing this trend, the Chewong are not engaged in the long term acquisition of wealth, which helps preserve their deeply engrained ideology of equality.

In the gateway village, while the men are working, at least at times, for money, the women are mostly confined to childcare and cooking. Nothing prevents them from cultivating crops, but they don’t seem to be doing that. Instead, they are becoming more passive in their settled lives. Howell observes them increasingly sitting about drinking beverages and eating cookies. Female obesity is a new phenomenon, she notes.

The Chewong may feel pressured by the Malaysian authorities to live in the settled village, but they are not helpless victims of modernization. They are fascinated by consumer goods, happy to have easily purchased foods, and to some extent willing to allow their society to change.

But the changes do not always go just one way. When she visited in 1991, she noticed that many Chewong had moved into the gateway village and were using purchased TVs and motorbikes. They seemed increasingly addicted to the consumer lifestyle. On her next visit in 1994, she quickly realized that many had returned to the forest, and the gateway village was mostly abandoned. The reason, the people told her, was that they disliked being so close to all the outsiders.

They also told her how they missed the forest foods and the wild game. The women appeared as if they were enjoying their active lives in the forest more than they had the passive lifestyle of the village. But they were weighing the advantages of both. Some seemed to prefer the forest, others the village, and still others moved for short periods between the two.

The continuing existence of the forest is only possible because their village backs up to an important game preserve, so the land is mostly protected from being logged. The Chewong thus continue to have the choice between the forest life, with the peaceful sharing and equality it entails, and the gateway village, where sharing is less possible and equality is harder to maintain, but consumer goods are easily available.

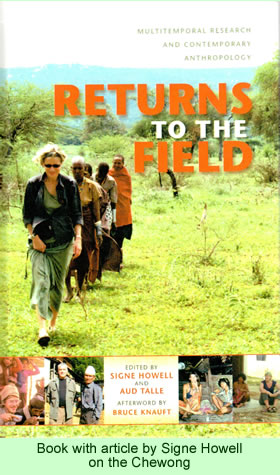

Howell, Signe. 2012. “Cumulative Understandings: Experiences from the Study of Two Southeast Asian Societies.” In Returns to the Field: Multitemporal Research and Contemporary Anthropology, Ed. Signe Howell and Aud Talle, p. 153-179. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.