Self-governance, community service, and communal lands are among the traditions cherished by the Zapotec that help them maintain their autonomy, interpersonal harmony and effective approaches to justice. This website reviewed a journal article about the Zapotec social and political system, called usos y costumbres, in 2005, but it is helpful to have a current, popularly-written review of their unique ways of organizing communities that are, at least in some cases, highly peaceful.

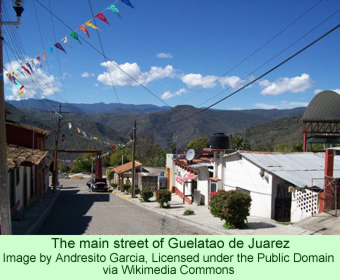

A carefully-written, lengthy article published in the online magazine Truthout last week examined the issues relating to these traditions in Oaxaca State, in southern Mexico. It focused on a couple Zapotec municipalities, Guelatao de Juarez, with about 800 inhabitants, and Capulalpam de Mendez, with about 1,500. Both are in the mountains 60 km (36 miles) from the state capitol, Oaxaca City.

A carefully-written, lengthy article published in the online magazine Truthout last week examined the issues relating to these traditions in Oaxaca State, in southern Mexico. It focused on a couple Zapotec municipalities, Guelatao de Juarez, with about 800 inhabitants, and Capulalpam de Mendez, with about 1,500. Both are in the mountains 60 km (36 miles) from the state capitol, Oaxaca City.

The authors, Renata Bessi and Santiago Navarro F., point out that of the 570 municipalities in the state, 418 use the traditional forms of governance referred to in English as “uses and customs,” while only 152 have adopted more conventional political systems. The unique, dedicated focus by the Zapotec, and the other, smaller, indigenous communities in Oaxaca, on keeping their traditional forms of government and social organization could inspire the rest of Mexico and, more broadly, Latin America.

The communities are governed, rules are set, and decisions are made by neighborhood, agrarian, religious, and town assemblies, with the general assembly, the highest level, having the ultimate authority over the entire municipality. Persons in positions of authority are not elected, however. Instead, the people follow their tradition of “cargos,” a hierarchical system where office-holders assume progressively responsible positions of service.

Children can begin lives of service by accepting cargos such as bell-ringers in the church, with the responsibility of marking the hours of the day for the people of the town. Services by adults can progress from general assistant to police assistant, project manager, town council, community mediator, and, finally, to town president.

Truthout interviewed the mayor of Guelatao, Jesus Hernandez Cruz, who had recently begun his cargo as mayor. He explained the ways the cargo system worked. By having individuals who are interested in service assume progressively responsible positions, they can effectively learn the needs and wishes of the community.

The mayor explained that no one earns money from their cargos, and that they work at tasks that best suit their own abilities. “The only thing one earns as one completes a good service is the respect and recognition of the town,” he said. However, according to another authority, the municipality does give municipal services such as electricity and water for free to people who provide cargos.

The provision of those free community services implies, however, that a stigma will be applied against people who do not fulfill their cargo duties adequately. Another element of the traditional organization of the Zapotec community is the tequios, the required, collective, community work projects that people perform, such as maintenance of roads and highways.

Jaime Martinez Luna, a Zapotec anthropologist, explained that these elements in the structure of the community help form the values and knowledge that have sustained the people for centuries. “We must understand,” he said, “what we are, not the ‘I’ or the ‘you,’ but the ‘we,’ and we should hold onto these principles in order to stop the interference of the vulgar and shameless principles of individualism. We shouldn’t enter into competition except to reproduce that which will be shared.”

He added that the Zapotec are against development that requires growth. They reject linear thinking, preferring circular and spiral ways of approaching issues because “men and women are not the center of the natural world. We are not owners of nature; we are owned by nature.”

Truthout emphasizes that normally the land in indigenous towns is owned communally. Land is not held as private property. All transfers of rights to use individual property must be approved by the assembly. If three years go by and a farmer does not produce anything on his land, the assembly can transfer it to another who does intend to make appropriate use of the property. Assemblies also have the authority to declare tracts of land as protected communal areas.

The mayor of Guelatao explained the system of justice in his town. Punishments for infractions of the laws may include jail time ranging from 12 hours, to 24 hours, to 3 days of incarceration. Fines and forced labor—for the benefit of the community—may also be imposed.

The community mediator, one of the higher level cargos, handles cases of justice involving theft, physical violence, and other types of crimes. He also helps out with issues that are beyond the scope of his responsibilities. Grave situations might require transferring the case to a higher level, the Public Ministry, but “the majority of cases are resolved here,” the mayor explains.

The self sufficiency of the two municipalities is assured because of resources produced by five local businesses: a toy factory; an ecotourism project; a crushed gravel pit; a water bottling plant; and a wood products mill using forest resources managed sustainably by the communities. The resources these projects generate support salaries for a small number of municipal employees: a librarian, a gardener, and an employee at the community cultural center.

Truthout does not dwell on the issue of autonomy in the two municipalities since, the authors write, the people themselves don’t speak much about it. But the authors do summarize their perception of the issue most eloquently. It is worth quoting their paragraph since it will convey the effectiveness of their writing and analysis. “Autonomy seems to be a daily reality that is breathed and felt in the harmony of the people when they go to participate in the tequio—collective work—or when they attend an assembly, organize to defend their land and territory, and celebrate and dance. The cargos of self-governance are still seen as a symbol of respect for the person who is chosen to give the service without being paid.”

Bessi, Renata,and Santiago Navarro F. 2014. “Across Latin America, a Struggle for Communal Land and Indigenous Autonomy.” Truthout. (Sunday, 20 July). http://truth-out.org/news/item/24981-across-latin-america-a-struggle-for-communal-land-and-indigenous-autonomy