It is always heartening when the news media update really important issues, such as the ways people cherish their love poetry, rather than produce more dreary stories about wars and murders, diseases and disasters. Two different reports appeared in the Philippine press last week about the ancient baybayin script, used by the Buid and a few other indigenous societies of the country to write their poetry, called ambahan, plus at times other kinds of texts.

In 1990, Gibson wrote that young Buid men traditionally ignored acts of courage and, instead, learned love poems to court women—an important aspect of their culture of peace. They used the ancient script that they preserve to help them memorize the poems, which are filled with gentle rather than aggressive images. But those conditions are changing.

In 1990, Gibson wrote that young Buid men traditionally ignored acts of courage and, instead, learned love poems to court women—an important aspect of their culture of peace. They used the ancient script that they preserve to help them memorize the poems, which are filled with gentle rather than aggressive images. But those conditions are changing.

The author of a 2009 blog post noted how ambahan poetry forms persist, but they are now being used to protest the practices of outsiders that are devastating Buid communities, such as mining, logging, and aggressive trespasses on native lands. A news report two years later described how the ambahan are still important expressions of feelings among the Mangyan peoples, the traditional societies of Mindoro Island, which include the Buid.

The baybayin script is used by the Tagbanwa on Palawan Island, the Buid, and their neighbors at the southern tip of Mindoro Island, the Hanunoo. All three societies preserve different variations of the written script, which derives from ancient writings used in South India called Brahmi. The baybayin consists of 17 cursive characters.

However, according to one of the news stories last week, the script is being preserved primarily by a few people in remote villages, and it is in danger of going extinct. Fely Montajes, a 40-year old Buid lady in the village of Batuili, knows and uses the Buid version of the baybayin script. She is obviously proud of her heritage: “I inherited this from my parents. This is one of the few things that is still our own,” she tells the reporter while she carves the characters on a piece of bamboo, sounding them out as she proceeds to inscribe her love poem. She adds that she learned some of the script from her father and the rest from her friends.

Buid who live in communities close to the cities are the ones in greatest danger of losing their connection with their ancient culture. Even some of the elders in the more remote communities no longer know the baybayin. An 82-year old resident of Batuili indicates that the number of people bothering to learn the script is dropping—less than a third of the elders in that village still know it. Say-an Reyes, the Batuili elder, says, “It’s important for people to learn the script [but] no one teaches [it to] the kids anymore.”

Bercelinda Babylya, a district official, describes how the script is still being maintained to some extent in the mountain communities. For many of the Buid, she says, the most important thing to focus on is obtaining food and the other basics of survival.

Emily Catapang, executive director of the Mangyan Heritage Centre, located in Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro province, has a somewhat different, and perhaps more hopeful, take on the survival of the baybayin. An important cause for her center is preserving the script, a key element in helping the Buid and the Hanunoo maintain and value their cultures. The Centre has people teaching the Hanunoo version of the script in 10 different schools.

She points out that some of the elders who know the script only use it for signing their names, but in parts of Mindoro there are signs on hospitals and markets written with it. The Centre is reaching out in other ways to promote the cause among the Buid and Hanunoo, such as through writing contests and reading traditional ambahan poetry. Also, people visit colleges, schools, and institutions around the country with outreach messages about it. And, in Batuili, Ms. Mantajes tries in her own way to reach out to others, encouraging the Buid to cherish their script.

A different Philippine news source reported last week on a couple baybayin documents treasured by the University of Santo Tomas (UST) in Manila, the oldest university in the country. The National Archives of the Philippines has just declared that two of their 17th century baybayin documents are National Cultural Treasures.

Evidently, those old baybayin documents were not love poems. The two that were celebrated last week were actually deeds of sale produced during the early period of Spanish colonization. Professor Regalado Trota Jose, director of the UST Archives, explained that the documents provide glimpses into the development of the baybayin script.

Also, they highlight the fact that women in ancient Philippine society had the same ability as men to buy and sell land. The two surviving deeds of sale, written in baybayin, date from 1613 and 1635. Prof. Jose explained that the baybayin was used in the Philippines before Islam reached the islands and before the Spanish entered the land. It has 14 consonants and three vowels, he said, but it is not really an alphabet. Archaeologists have discovered a variety of ancient artifacts with baybayin inscriptions on them.

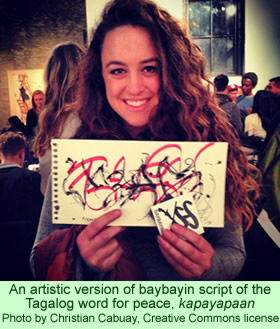

Some Filipinos are trying to resurrect the ancient baybayin script through their artistic expressions. For instance, Christian Cabuay, who was born in the Philippines but raised in the San Francisco Bay area, is instructing and propagating his artistic visions of baybayin as Filipino calligraphy. He demonstrates, lectures, paints, hold exhibitions, and, as one website indicates, he “tirelessly [advocates] a reawakening of the [Philippine] indigenous spirit through decolonization and Baybayin.”