Ten years ago, during the first full year of this website, almost nothing was reported in the Indian news about the then obscure Kadar society. The situation has changed dramatically since then. Three news reports on the Kadar were published last week alone. This society and its problems seem to have captured the attention of some important media in South Asia.

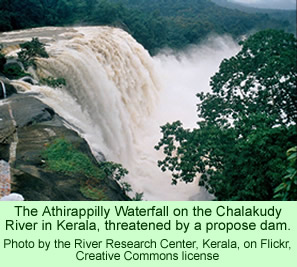

The first story published at the beginning of last week by Scroll.in, an online Indian news service, reviewed the status of the proposed Athirapilly hydroelectric power dam on the Chalakkudy River, which threatens a couple nearby Kadar communities and the Athirapilly Waterfall located just below the dam site. The essence of the report is that the Kadar are fighting what appears to be a renewed effort by the state—Kerala—to push for the dam construction.

The first story published at the beginning of last week by Scroll.in, an online Indian news service, reviewed the status of the proposed Athirapilly hydroelectric power dam on the Chalakkudy River, which threatens a couple nearby Kadar communities and the Athirapilly Waterfall located just below the dam site. The essence of the report is that the Kadar are fighting what appears to be a renewed effort by the state—Kerala—to push for the dam construction.

This story—of a small, hitherto obscure, peaceful tribal society, ignored and then threatened by the vast bureaucracy of the Indian and the state governments—may be one of the reasons that the media has focused so much attention on the Kadar over the years beginning in 2006, as a review of the news about the group implies. An article last year in a scholarly journal reviewed the way the Kadar have been treated by surrounding communities and by bureaucrats over the issue.

The report from Scroll.in last week describes the attempts by the state to start construction of the dam, the various reviews of the project over the years, and the controversy surrounding the Kadar communities and their hopes to survive. The review makes it clear that the dam proposal has been approved by various agencies and committees beginning in 1998, but the opposition by the Kadar, expressed in meetings and public rallies starting in 2006, began to turn public opinion against it.

An environmental minister at the national level, Jairam Ramesh, issued a show cause notice in 2010 that required reasons why such a damaging project should not be stopped. His action effectively shut down the proposal. A group called the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, chaired by Madhav Gadgil, reported in 2011 that the dam would irrevocably alter the ecology of the Chalakkudy River, which was threatened by the proposed dam, and harm the Kadar communities.

More recently, however, the High Level Working Group, chaired by K. Kasturirangan, came to a different conclusion. It decided that the project could move forward. According to the Scroll.in news report, the Kerala electricity board took this as an approval to move ahead on the dam project. The national Ministry of Environment allowed the state to reapply, and it was then referred to the River Valley Committee for clearance—for the fourth time. At its meeting in July 2015, that committee withdrew the show cause decision of Mr. Ramesh from 2010. The committee ignored the fact that the Kadar in the affected villages had obtained approval of their Community Forest Rights under the provisions of the Forest Rights Act of 2006; it accepted the information provided by the state—that the project will not harm any Kadar people; and it ignored the contradictory information provided by the Kadar themselves. It approved the project.

In response, a tribal council of the Kadar communities held a meeting on August 23. Geetha, a Kadar leader, had written an open letter in July stating that the Athirapilly project “will destroy 28.5 hectares of riparian (riverside) forests that sustain our way of life.” The purpose of the meeting was to draft a resolution opposing the dam. The Kadar clearly will continue to do everything they can to protect their forest, livelihoods, culture, and society.

But there were two other news reports last week about the Kadar. One, published by the New Indian Express on Tuesday, describes the business processes which some Kadar communities are using to improve the marketing of the non-timber forest products they sell. The Kadar at the Malakkappara community in Kerala have started releasing their products, such as honey, amber and cardamom, labeled with the brand name “Kadars.”

The Kadar are seeking to interest other nearby tribal societies, such as the Malayan and the Muthuvan, into also marketing products they gather under the Kadars brand name. The people are making “staggering” profits, according to the news report. Visitors are even surging into their hamlets in search of the products.

According to Mohanan, a local official in Malakkappara, the district government is providing training to help the Kadar sell their forest products better. Once that training process is complete, the Kadar plan to organize an exhibition in Athirapilly or Vazhachal, where the well-known waterfalls attract many tourists, to further promote their sales. If the other tribal groups want to launch their own products under their own names later, they are free to do that.

Mohanan added, “another Kadar ooru [village] in Vazhachal is in the process of commencing production of indigenous products for sales to tourists and we will be looking for a business tie-up so that we can sell our products in their stalls.”

The third news report on the Kadar last week, appearing in The Hindu on Thursday, was much less upbeat. The issue is that the number of males in some of the Kadar colonies has dropped to very low levels, which is limiting the stability of the population. In the Cherunelli settlement, near the Nelliyampathi hill station and the famous Parambikulam Tiger Reserve, there are now 9 males and 45 females. About 15 years ago, the colony had 150 males. In another settlement, Pullukad, there are 8 males and 29 females. In other settlements—Karappara, Aditharanda, Ailoor, and Kalchadi—the situation is similar.

The distress is caused by alcoholism and by an excessive use of tobacco products, which exacerbate the problems of poverty and malnutrition, the newspaper reports. An elder at the Cherunelli colony, Ravi Mooppan, compared the plight of his village with the better known Kadar communities in the Vazhachal region.

“Now they [the Vazhachal Kadar] are getting better privileges and their forest rights have been approved by the government. In the case of those who are living in adjacent Nelliyampathi, life is a constant battle against heavy odds including ill-health and lack of social security measures,” he said. These Kadar have not gotten their Community Forest Rights approved for them, they have no tribal schools in their region, and the major plantations in Nelliyampathi are not doing well, so Kadar laborers have lost their jobs.

“The Kadar community in Nelliyampathi needs immediate intervention of the State government,” argues S. Guruvayurappan of the Asryam Rural Development Society, which campaigns against tobacco and alcohol use among the Kadar.